Art History

5 Reasons you need to know about The Rorke’s Drift Art and Craft Centre

Introduction

Hi, I am artist Lillian Gray, and today I would like to tell you about the famous Rorke’s Drift Art and Craft Centre.

The Rorke’s Drift Art and Craft Centre has been described as “the most famous indigenous art centre in South Africa!” It is world-renowned for its Pottery, Tapestries and Printmaking. This centre gave rise to some of southern Africa’s most celebrated artists.

These include artists like Azaria Mbatha, John Muafangejo and Cyprian Shilakoe, known for their printmaking. The celebrated weaver Allina Ndebele and the remarkable ceramicists Gordon Mbatha, Dinah Molefe and Elizabeth Mbatha. These artists are only a selection of a large group of black artists who studied at the Rorke’s Drift Art and Craft Centre.

The centre played a crucial role in South African Art History and still has a major influence on South African Art today. So what made Rorke’s Drift so unique? And why do you need to know about it? Here are five main Reasons. Come along as I share this remarkable story of triumph, tenacity and talent.

It played a key role in South African art for those who studied there and the many it influenced. It has been described as “the most famous indigenous art centre in South Africa.” The centre gave rise to some of southern Africa’s most renowned artists. These include artists like John Muafangejo, Azaria Mbatha, Bongi Dlomi, the weaver Allina Ndebele and the ceramicist Gordon Mbatha.

The location of Rorke’s Drift Arts and Craft Centre:

The location can be a little bit confusing when doing research on the Rorke’s Drift arts and craft centre. The school has moved over the years.

In the late 1950’s the National Party government proclaimed the Rorke’s Drift farm reserved for the exclusive use of white people. The Rorke’s Drift center had to move again and was situated near Dundee, where it is still operating today.

Rorke’s Drift is also the location of the Battle of Rorke’s Drift that took place in 1879, a historic site where British troops defeated a large Zulu army during the Anglo-Zulu War.

1:Education for all races during Apartheid

The Rorkes Drift Arts and Craft Centre offered arts and crafts training for black people during the oppressive Apartheid Regime. During this time Apartheid policies denied a formal education to black people. The centre blossomed into an exceptional space where people of all races were mixed to share ideas, insights and skills. Not only were people from different races but also various African and International countries. Later the centre also established a Fine Art School with a 3-year diploma for black students.

One of the only other art schools available to black artists in the country at the time was the Polly Street Art Centre in Johannesburg.

Needless to say, the Apartheid government disapproved of these establishments, but more on this later.

The initial idea that led to establishing the Rorke’s Drift Art and Craft Centre started in Sweden, not South Africa. People abroad have been hearing about people’s suffering under Apartheid. A Lutheran Church in Sweden wanted to alleviate the hardship in the Apartheid Homelands of South Africa, and so the concept of selling African crafts in Sweden was born.

Two trained artists, Peder and Ulla Gowenius, were sent to South Africa. The initial idea was not to start an art school but to teach arts and crafts at a rural hospital to its patients. The hospital was filled with recovering TB patients. Most sat around quite depressed while waiting for their medicine to do its magic. Peder and Ulla were meant to teach them craft as a form of occupational therapy; however, when the Gowenius couple saw the oppressive Apartheid in action, their aim changed. They wanted people to feel in charge of their lives.

So this famous art centre started inside a small rural Hospital in Zululand. Once it grew popular, the centre required more space and moved to its own buildings. These buildings were abandoned and located at the scene of the famous Rorke’s Drift Battle – an infamous battle between the Zulus and British. Because the centre was a church initiative, it was initially called The Evangelical Lutheran Church Art and Craft Centre, in short, ELC; however, it became simply known – as Rorke’s Drift.

Initially, three leading production studios were established at Rorke’s Drift, weaving, fabric printing and pottery. Later a Fine Arts Department was added, focusing on Printmaking and Photography.

These are basic craft skills, so what made Rorke’s Drifts creations so unique? Glad you asked; it leads to point number two.

2: Unique Fusion – European Practices and African Storytelling

Rorke’s Drift created a unique fusion; of European practices mixed with African storytelling and styles. European teachers were careful not to influence their African students too much. They wanted them to maintain their Africancity.

The founding couple deliberately decided that teachers should focus on teaching art techniques and impose as little as possible on students’ unique African Heritage. It was a delicate combination of technical assistance and traditional African storytelling and designs.

Rorke’s Drift was a hub of creativity and individuality. The artists developed diverse styles and grew their own voices. At the start of the art centre, there was this natural cross-pollination of skills as different departments interacted with each other. Linocuts, translated into fabric prints, some designs became murals and other tapestries – a true hub of creativity.

Let’s explore how this impacted the main departments at The Rorke’s Drift Centre.

In the weaving department, some functional rugs were made. However, it is in the tapestries that we see a unique creative style taking shape. Apprentice weavers were encouraged to achieve artistic independence and weave their own designs. Designs were never reused, although similar themes were sometimes re-interpreted. The tapestries were usually figurative, not abstract, and incorporated scenes from folklore, village life, Bible stories, or important events. Alina Ndebele is celebrated today for her freestyle weaving and sharing Zulu Folklore stories.

In the pottery department, some traditional Zulu and Sotho Coil methods were used; after all, clay pots have been made in Africa for generations. However, designs were conservative and hardly changed over the years. At Rorke’s Drift, students learnt complex kiln methods. They were also taught how to produce functional tableware for urban consumers.

But what made Rorke’s Drift pottery so unique was that the students were encouraged to be creative and develop their own designs. This individualism gave rise to a new style of pottery that is still easily recognisable today. One can spot Rorke’s Drift pottery a mile away.

The women continued using the traditional methods, working by hand, creating more organic free forms. The men preferred the kick-wheel and decorated their pots with the sgraffito technique. This gender branch in style in the studio’s ceramics —women, coiling, men throwing— is still how it is being done to this day at the craft centre.

The pottery was distinctive, individual and essentially African. Though much of the pottery is functional some are sculptural, such as the works of Dinah Molefe and Elizabeth Mbatha’s. Today these ceramics are the most sought-after and desirable pieces. They tend to fetch high prices at art auctions.

Of all the arts and crafts created at Rorke’s Drift, it is the prints that fetch the highest at art auctions. Today the most famous prints can be spotted quickly for their well-known “Rorke’s Drift style.” There are even artists copying this style that never even attended the school! But why?

The centre didn’t create cookie-cutter artists. Everyone was allowed to… no, encouraged to develop their unique style. So how did this idea of a coherent ‘Rorke’s Drift style’ take root? It is mainly due to the popularity and success of two artists, Azaria Mbatha and John Muafangejo. Sales were of great importance to Rorke’s Drift students. They needed a sustainable income. Artists, Mbatha and Muafangejo’s works sold.

Therefore they were greatly admired and emulated by others. Today many artists also copy Muafangejo’s style to pay homage to him as a form of respect. Azaria Mbatha played a fundamental role at the Rorkes Drift school. He left to train at a prestigious art school in Sweden. He then returned to Rorke’s Drift to teach. Students were eager to learn from this artist and hear about his experiences abroad. It is quite natural that other students wanted to emulate Mbatha.

Nevertheless, it is important to remember that various artists with diverse styles were present at Rorke’s Drift. The catalogue compiled by Philippa Hobbs of Rorke’s Drift’s artists includes over eighty artists associated with the project.

3: The artworks contained hidden messages

The most remarkable thing about the art created at Rorke’s Drift is that it contains hidden messages. How cool is that? At the time in South Africa, Apartheid restricted freedom of communication and expression. You couldn’t just pipe up and say, “This government sucks” That would lead to serious consequences. According to Ulla, “Words were dangerous.”

Hidden metaphors allowed students to critique the Apartheid Regime and promote a better, inclusive future for South Africa during censorship. Saying these things out loud would have had severe consequences. Ulla and Peder wanted students to express themselves; they wanted to develop a strong voice; however, they had to be careful. Informants were everywhere, even at Rorke’s Drift. At the time, anybody against Apartheid was labeled a communist, and alleged communists were treated like terrorists. Peder and Ulla chose not to discuss politics with the students but rather to encourage storytelling.

Because Peder wanted the students to be true to their roots, he was disappointed when Azaria Mbatha insisted on depicting Bible stories. However, he was soon astonished. Early on, when arts and crafts were still being taught in the tiny rural hospital, Azaria Mbatha produced an astounding artwork. He depicted the biblical story of David and Goliath… but with a bit of a twist. David was black, holding the severed head of a white Goliath. The Israelites were represented as black people.

Their exalted status suggested by the fancy robes they wore. Their enemy, the Philistines, were represented as white, dressed in short military tunics running away in terror. The use of black and white in this linocut speaks directly to the racial tensions in Apartheid South Africa. The start contrast of black and white also depicts the struggle between good and evil; Usually black is used to represent evil and white used to depict good. This artwork flips this conventional belief on its head.

Peder was amazed. A conquering black man was refreshing to the typical image of a suffering African. Peder quickly realised the print held a message that was forbidden at the time in South Africa. It was using a Biblical story to make a political statement. However, this message could slip past censorship. You see, the Apartheid Regime saw themselves as Christians. They would not restrict or sensor Bible Stories.

Peder learnt through Mbatha’s work that religious subject matter could carry other meanings and be a conduit for socio-political comment. Mbatha’s David as a young African hero occupying the high moral ground and defeating a white Goliath was a prediction of a triumphant outcome to the racial oppression.

4: Grit and Perseverance against the Apartheid authorities

This centre blatantly went against the authorities of the time, who was pro-segregation of races. However, from the start, the Apartheid government couldn’t intervene with the school too much. This was because the Art School was a church initiative. The Apartheid National Party proclaimed to be followers of Christ, yet, they branded people, classified them, and created hatred and violence. They couldn’t just shut down a church operation. However, there were existing Apartheid controls they could use.

According to Apartheid law, all non-whites in South Africa had to carry a Passbook. It was designed to control the movement of Black Africans. Blacks needed to carry these books at all times when they were not in the demarcated homeland areas. People often had to ‘violate’ The Pass Laws and thus lived under constant threat of fines, harassment, and arrests. The Government used these books to monitor and track Rorke’s Drift students’ movements, sometimes hampering their education. There were ongoing fears that students and workers could get evicted anytime from The Rorke’s Drift Arts and Craft Centre.

You see, the existence of this school really vexed them. The initial aim of Rorke’s Drift was to create a school wholly managed and taught by Africans. Local African artists were sent to Sweden for training and, on their return, worked as teachers at the centre. Various black students were educated and trained to manage specific areas of the school, such as bookkeeping and other departments relating to the general running of the centre. This was extremely rare during Apartheid.

Apartheid had an Economic incentive; it needed cheap labour for the booming mining industry. For black people to keep working in these harsh conditions, it was imperative that they remain uneducated. Bantu-Education aimed to train the children for manual labour and menial jobs that the government deemed suitable for those of their race. It was intended to embed the idea that Black people were to accept being subservient to white South Africans. As you can see, the training offered at Rorkes Dirft was not designed to keep people in the labour force.

To the Apartheid government’s horror, The Swedish Church also created a market for African Arts and crafts abroad. At first, the Church sold Rorke’s Drift products only in Sweden. Ulla used this to the school’s advantage. She informed the authorities the school has become famous in Sweden, and it would reflect poorly on the government if it closed down.

Initially, this argument aided with Visa extensions and Passbook controls for students. As the school became popular in Sweden, products started selling in other parts of Europe and the United States. Initially, a substantial portion of the work was exported to generate income. However, Rorke’s Drift products quickly also gained popularity amongst the South African white middle class. This was due to the exceptional quality of the goods created at Rorke’s Drift.

The history of Rorke’s Drift is complex, and cannot be covered in this video in detail. Here is quick overview so that you can understand how Apartheid impacted the Fine Arts Department specifically. The first phase of the school witnessed the evolution of several significant artists. Eventually all these artists have moved on, new leadership has come and gone and buy this mid 70’s a new generation of artists and teachers arrived. The centre focused more on developing the curriculum into an intensive 3-year arts diploma. Under the directorship of Jules and Ada van de Vijver various new printmaking techniques were added, such as screen printing, dry point and etching. They also introduced photography as a subject.

1976 was the time of the Soweto Uprising, signalling the beginning of an intense new wave of anti-Apartheid revolt inside the country and an increasing campaign of boycotts internationally. Various internal and external factors started to hamper the development of the Fine Arts Department at Rorke’s Drift.

The government started to clamp down. They would refuse visas for art teachers. They would give existing teachers 24-hour notice to leave the country, forcing them to return to Sweden. This created staff shortages at Rorke’s Drift. The centre encouraged expanding its black staff. However, it was challenging for black people to acquire a professional background to meet the standards set for teaching at the centre. Finding qualified teachers to keep the Fine Arts Department running became almost impossible. The high staff turnover caused an incoherent curriculum in the Fine Arts Department.

Together with many international countries, Sweden’s announced their first sanctions on South Africa. This intensified the Apartheid disruptions at Rorke’s Drift. One teacher remembers a visit by police helicopters with a load of police dropping in for inspection. At other times, Special Services snooped and asked various questions. Jules and Ada van de Vijver described living and working at Rorke’s Drift in the second half of the seventies as very exciting and intense. At one stage, the authorities declare the Rorke’s Drift farm a whites-only area, making it impossible for black students to get to classes.

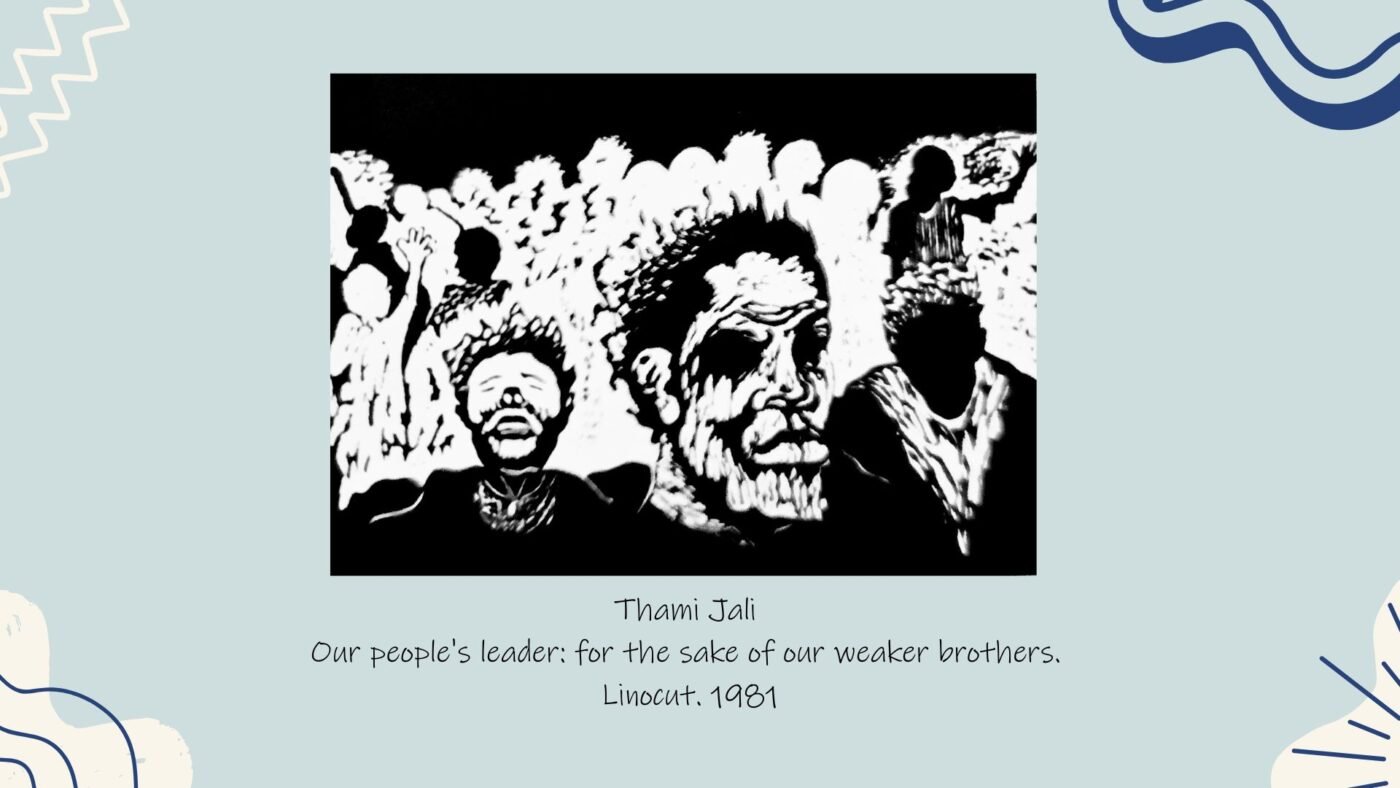

There also appears to have been tension between the Fine Arts and Crafts departments at the centre. The Fine Art section cost the Church money, whereas the Craft section generated income. The fine art students tended to come to the centre from the cities and were more politically motivated, while the people attending the craft departments were primarily from rural homelands. New fine arts students had lived through the Sharpville Massacre (1960) and the June 16 Soweto Youth Uprising (1976.) Steve Biko’s death in detention the following year (1977) was a further crucial influence on the students’ thinking. The art moved from subtle messages to outright protest art.

Artist Thami Jali created a Linocut called Our People’s Leaders. Jali felt that many of his peers at the Centre needed to be politicised. His work aimed not only at his peers but also targeted the leaders of the struggle. In this linocut, he pleads for them to recommit themselves to the cause. Their apparent reluctance is addressed in the subtitle inscribed on the work, For the Sake of Our Weaker Brothers.

Heart in the Oven, a woodcut of the same year by Avhashoni Mainganye, combines more familiar icons of civil conflicts, such as the carrying of Hector Peterson’s body and a police vehicle patrolling an empty gathering place. This disturbing collage of images may offer an unexpected message of hope, for a dove appears from the dead boy’s mouth, suggesting the Holy Spirit. The two enormous hands that emerge from the heavens on either side of the bird seem to offer a divine blessing – perhaps an acceptance of violence to achieve freedom.

Student Tony Nkotsi produced the artwork “Portrait of a Man” in 1982. A linocut that captures a likeness of Biko, alert and alive, although having already sustained the fatal injury that marks his temple. His hands almost seem to reach out of the picture plane towards us. He holds a key engraved with the letters ‘RSA’. RSA stands for “Republic of South Africa,” It suggests that Biko and the principles he stood for provide the key to unlocking a better future for South Africa.

Eventually, the Fine Arts section of Rorke’s Drift closed in 1982. It was a great shock to many people in the art community of South Africa. Even though the Fine Arts Department did not survive Apartheid, it was still a remarkable space and a worthy achievement for the time.

The founders, Peder and Ulla Gowenius and all the teachers involved achieved what many would today consider impossible.

- They empowered black students to generate their own income.

- They offered education outside the segregated Bantu education system.

- They created a community in which everyone mattered.

- Over time the centre produced various internationally acclaimed African artists.

- The Art and Craft Centre became a model for many centres that have been established throughout Southern Africa.

- Fine Art Diploma graduate students filtered into many areas of South African life, some becoming educators at various art centres in South Africa.

- It could be said that the expertise taught at Rorke’s Drift aided the political struggle directly. The artists made banners, T-shirts, and posters, all using Rorke’s Drift printmaking skills.

- It enabled various black students to study abroad; Allina and Azaria received training in Sweden and returned to teach at the centre—something rare during the Apartheid Regime.

- It aided Azaria Mbatha in immigrating to Sweden permanently. There, Azaria completed studies in Social Sciences and achieved a Doctorate in African Historical Symbolism.

- It also enabled Allina Ndebele to start her own business.

- It grew the international audience and its appreciation for African Art and Craft.

Rorkes Drift achieved all of this despite the obstructive Apartheid government at the time. Looking at history, art often seems to flourish under political oppression and prohibition. According to Peder, Apartheid contributed to the development of Rorke’s Drift. The rules of Apartheid created a bunch of frustrated but creative humans who needed to express themselves.

The craft centre survived despite all the trials and tribulations caused by the Apartheid Government. It is still operating today, and you can still purchase authentic Rorkes Drift pottery, tapestries, rugs, baskets and hand-printed materials. This legacy of high-quality African craftsmanship flows into my final point—number five.

5: Rorke’s Drift Catalogue and Authenticity

The Rorke’s Drift Arts and Craft Centre kept a meticulous catalogue of all craft objects produced at the centre. All craft objects created at the centre, such as pottery and weaving, were marked with this distinct leaf logo. Each item was assigned a number and catalogued according to the manufacturing date and the artist’s name. This means all the crafts can be traced back to Rorke’s Drift.

The Fine art Students at Rorke’s Drift were also taught to catalogue their artwork and keep a sales record. Printmaking techniques enable artists to do print runs of the same design. Professional artists decide how many prints to print of one carving or etch. They are numbered and kept to a limited print run.

Artists, who studied at Rorke’s Drift, were encouraged to record everything they produced meticulously. They were taught to limit print runs by cancelling a woodblock, etch or lino. Here you will see the cxd in the top left corner and the date on a John Muafangejo woodblock. This means this block has been cancelled. It prevents this artwork from ever getting reprinted.

Art Investors love detailed records because the work can be traced back to the artists, proving that it is an original work. It also makes it much harder for fakes to enter the market. This enables the work to increase in value over the years.

Conclusion

And that’s it for my lesson on the remarkable Rorke’s Drift Arts and Craft Centre. I am artist Lillian Gray, and I love teaching art and art history.

This is a reminder that you can shop various worksheets for all ages online on our TpT website. Connect with us on social media, and let us know what video you want to see next.

This Art and Craft Centre became a model for many entries that have been established throughout southern Africa.

The pictures created at Rorkes Drift tell vital stories and lives on to this day. This is because art is a universal language – a picture speaks all languages.

Sources:

Rorke’s Drift Empowering Prints – Twenty Years of Printmaking in South Africa by Pippa Hobbs and Elizabeth Rankin. Double Storey Books, A Juta Company. 2003.

BUY OUR RORKE’S DRIFT WORKSHEETS

Worksheet pack that includes notes and fun activities. Ideal for art students and history students to learn more about the Rorke’s Drift Art Center