No products in the basket.

Art History

5 ways in which Lady Skollie Honours the Khoisan culture in her artworks.

Introduction

Hey there, art enthusiasts! I’m artist Lillian Gray, and today I’ve got something exciting to share with you. Get ready to meet the vibrant South African artist known as Lady Skollie!

We have two videos on this remarkable artist. The previous one deals with more hard-hitting subjects and artworks, and this one focuses on how Lady Skollie incorporates the Khoisan religion and culture into her artworks.

Oh, and by the way, I’ve got some awesome worksheets related to Lady Skollie available on our TpT Store. They’re designed for different ages and are loads of fun to do, so make sure to check them out!

Lady Skollie is a renowned South African artist. She gained popularity for her large, bright artworks that spark conversations and challenge people’s beliefs. She has a unique art style that draws inspiration from Khoisan cave paintings. She uses various art mediums, including acrylic painting, watercolours, crayons, and printmaking, such as lithographs and linocuts.

Her work draws inspiration from her personal experiences, as well as South African history, politics, social issues and her Khoisan Heritage.

She was born in 1987 in Cape Town as Laura Windvogel. Over the years, she crafted her art name Lady Skollie. The name is a complete oxymoron. Lady refers to European conventions, especially the expectations placed on women in British society. Skollie is a word used to describe a male person of mixed race in South Africa who is an outcast, an uncouth thief or a thug.

Growing up in the new South Africa, in the Cape Coloured community, came with various labels and stereotypes. She was eager to understand what being coloured truly meant. She studied her Khoisan ancestry and was keen to reclaim her heritage.

Get ready to explore the five ways in which Lady Skollie Honours the Khoisan culture in her artworks.

1. Storytelling

The Khoisan religion strongly relies on the power of storytelling and oral traditions. Folktales are passed down through generations, conveying important moral and spiritual lessons while preserving cultural heritage.

And this is ultimately what Lady Skollie is all about. She is a storyteller. Through her art, she delves into the history of the coloured people of South Africa. It is a complex history but here is a brief overview.

The coloured people of South Africa were formed over many years and have diverse ancestry. However, it all started with the Khoisan tribes in Southern Africa.

The Khoisan is a collective term used to refer to a collection of tribes in Southern Africa. Some of the tribes were cattle herders, such as the Khoi Khoi and some gatherers, such as the San. The word San means “people who pick things up from the ground. It refers to a nomadic lifestyle of living off the land. KhoiKhoi means “men of men” or could be translated to “the real people” Together, these words formed Khoisan. San + Khoi Khoi = Koisan.

Genetic analysis has revealed that the Khoisan are one of the oldest people on earth, if not the oldest. They are often described as ‘the world’s first or oldest race’ and ‘the first people in South Africa.’ It is believed that these Khoisan tribes have populated Southern Africa for up to 140 000 years and maybe even more.

The Khoisan was first forced to move further south by the Bantu expansion. Then, the Age of Discovery followed, during which seafarers from a number of European countries explored the new world. Ships started to arrive in the cape from the Portuguese and the Dutch. The first European settlement in southern Africa was established by the VOC in Cape Town in 1652.

It was created to supply passing ships with fresh produce. The colony grew quickly and Dutch farmers moved in. As the Dutch took over more and more land to farm, the Khoisan tribes were dispossessed. Some were exterminated by systematic commando raids organised to kill Khoisan. Others were incorporated into colonial society as domestic servants and farm labourers, so their numbers dwindled.

Interactions between the Dutch, British settlers, Khoisan, and neighbouring Bantu populations led to a unique mixed-race community known as the Cape Coloureds. Enslaved individuals from Malaysia, Indonesia, Madagascar, and India were also brought in by the British, further adding to the diverse ancestry of the Cape Coloured population. Once slavery was abolished, there was still segregation, with a clear differentiation between the races. This eventually became the oppressive Apartheid regime.

During Apartheid, people were separated into four different racial classes. White, Coloured, Black and Asian. Each class had different rules and regulations and different experiences under the oppressive apartheid regime. To this day, in South Africa, we differentiate between black people and coloured people.

“I know the term coloured can be seen as derogatory to some, but we still use it“.

Lady Skollie

1994 marked the fall of the oppressive apartheid regime, and a New South Africa was born. Previously suppressed cultures were now allowed to flourish.

Throughout Colonialism and Apartheid, many stories were white-washed, told from the dominant white government’s perspective. With her artworks, Lady Skollie sheds light onto various historical moments, forcing viewers to reframe them and uncover details that used to be covered up.

Examples are artworks depicting influential Khoisan women such as Krotoa and Sarah Baartman and the devastating impact of the “Dop Stelsel” alcohol on the coloured people of South Africa. She does not hero-worship the arrival of the Dutch but instead highlights the destruction they caused to the Khoisan Culture.

She also focuses on problems within her community and in South Africa in general. She is a feminist and activist opposed to violence against women. Her art has strong messages about consent. Much of her work concerns women rising above abuse and saying no to violence.

Even though her art style draws from the world’s oldest race, the Khoisan, her messages are current. Lady Skollie’s art is this unique fusion of humour, violence against women, Khoisan Heritage and the destruction of Colonialism and Apartheid.

She describes her own work as ‘fire, ritual, Khoisan.’

2. Khoisan Cave Paintings

The Khoisan is synonymous with cave paintings done in rich earth tones. Khoisan cave paintings paintings can be found throughout most of southern Africa and as far north as Tanzania. The highest concentration of them is in South Africa. It is believed to be the oldest art form. Some are estimated to be around 27,000 years old but may be as old as 40,000 years old.

The cave paintings are stylised and share some distinct characteristics. They are generally drawn from a side view. It was believed that many of these cave paintings depicted hunting scenes, but in fact, scenes that depict hunting are scarce. Anthropologists now believe they are a product of religion, drawings of shamanistic rituals, only displaying animals with special spiritual significance.

Many of these cave paintings show lines of processions, people gathering for rituals, dances and social occasions. Some drawings depict figures that are half human, half animal, such as men with Eland heads or cloaked figures wearing Eland skins. Figures that are half-animal, half-human hybrids called therianthropes.

Men are generally depicted carrying a bow and arrow and or hunting bags. Their calves tend to be pronounced. Women’s bums and thighs are emphasised and they often carry digging sticks. Animals are always drawn from the side to identify the specie quickly and are hardly ever seen lying down.

Lady Skollie incorporates some of these traits into the depiction of her figures, generally using side views, elongated arms and legs with well-defined calves and bums. However, she also incorporates her own elements. Usually, Khoisan paintings omit faces, whereas Lady Skollie depicts them clearly to convey various emotions, which aids her storytelling. In some cases, she also adds extra limbs.

A beautiful example of her honouring Khoisan Cave paintings is her design for the R5 coin.

In 2019 she was commissioned to design money commemorating the 25th anniversary of South Africa’s democracy. Her design mimics the iconic photos of South Africans standing in long meandering queues in the country’s first democratic elections. Lady Skollie’s design depicts Khoisan figures standing in line for the ballot box.

“The thing I want people to know about queueing is that one day you will be in front.”

Lady Skollie

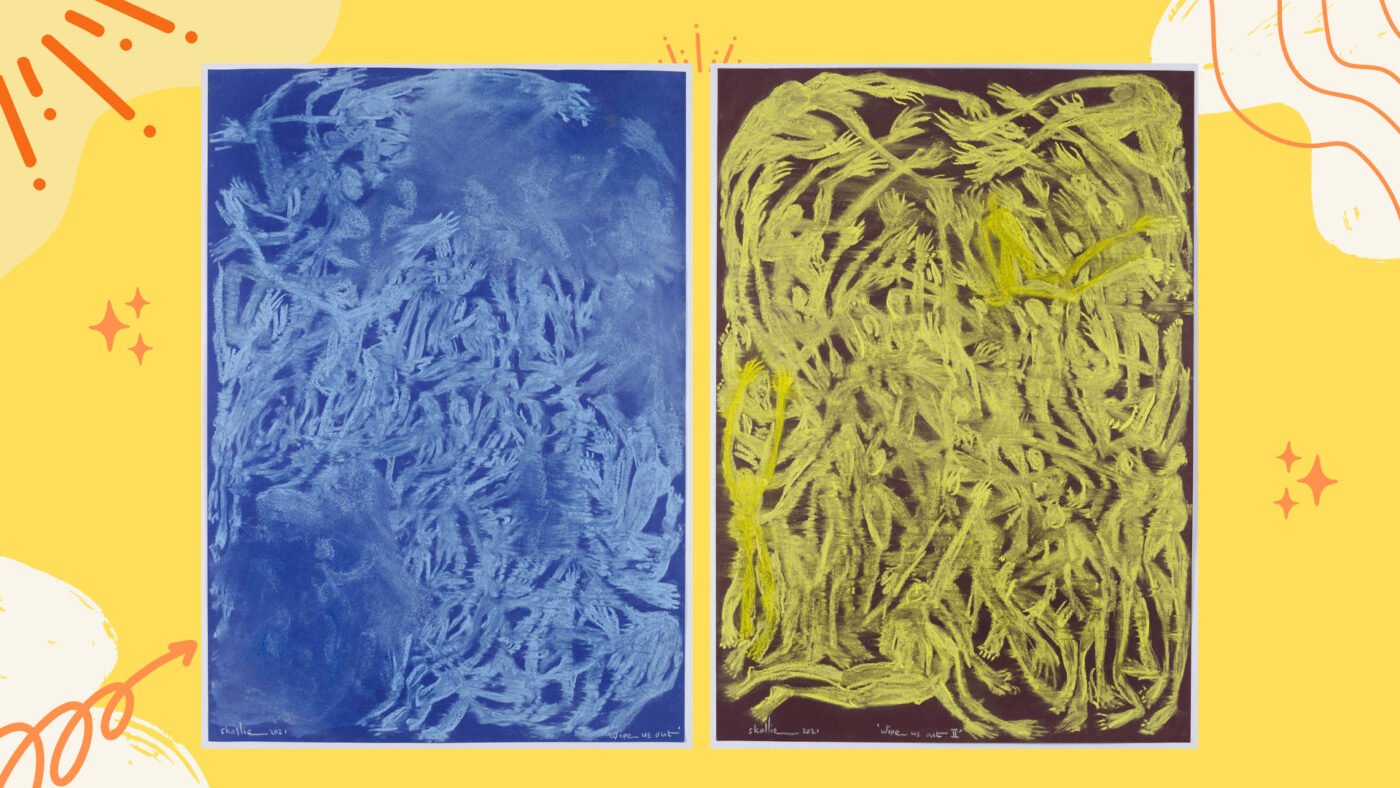

When it gets to the use of colour, Lady Skollie tends to break away from her ancestor’s influence. Khoisan paintings are usually done in earth tones such as ochers, reds, oranges and yellows. Lady Skollie often depicts some of her central figures in orange; however, her art is mainly known for its bright, vibrant, bold use of colour.

She loves modern fuchsia pink, neon greens and lumo yellows combined with ultramarine blues and stark black, creating high-contrast images. While the bushmen have limited art supplies, Lady Skollie combines watercolours, acrylic paint, ink, crayons, collage and even gold leaf to create striking artwork.

Sometimes Lady Skollie paints large murals on gallery walls. This echoes the Khoisan cave paintings that are found in small shelters or rock overhangs.

“I am creating works based on “the traditions of Khoisan storytelling, imagining a world of cave drawings depicting our pain.”

Lady Skollie

As a Khoisan coloured woman, I really like mark making; I think it’s in my blood, I want to have something tangible that I created in the space”

Lady Skollie

To her, it is all about reclaiming the space. Standing up and saying I was here. Often these murals are site-specific, meaning that the location is important and aids the message. Her famous work, known as Kween Mother, was painted in London. It is a massive Khoisan Kween invading the gallery.

The location is noteworthy since it was in London that an influential Khoisan Woman, Sarah Baartman, was paraded as a freakshow attraction. With this work, Lady Skollies returns as a Khoisan decedent, a Kween, a mother, victorious, despite colonialism.

And also because I want my drawings to represent giant pop culture cave drawings, a representation of what could have been if we were not eradicated into the earth,”

Lady Skollie

When studying Khoisan Cave Paintings, you will soon spot various types. There are Fine-line drawings, Engravings and Prints. One can draw parallels between these traditional Khoisan techniques and some of Lady Skollie’s art techniques—bum prints vs hand prints.

When dating Khoisan Cave Paintings, one can gradually see the loss of skill over the years.

The older cave paintings used fine-line quality that required highly skilled painters. Later the paintings became rough and unrefined. It appears that, as pressure was exerted on the culture, the quality and skill diminished. It starts with fine-line paintings and progresses to crude finger paintings once the settlers invade their lands. In a way, Lady Skollie’s is a contemporary cave painter. Losts of the old cave panting skills are now lost, but she is injecting modern methods with this old craft.

3. Pattern, Repetition, Rhythm, Trance.

Khoisan religious practices often involve rituals, dances, and trance-like states that allow individuals to connect with the spiritual realm. These rituals are typically performed by shamans or spiritual leaders who act as mediators between the community and the spiritual world.

The shamans are believed to have the ability to communicate with the divine, interpret signs and omens, and provide guidance and healing to their communities. The dances typically take a circular form, with women clapping and singing and men dancing rhythmically. When entering a trans-state, hallucinations occur. In some cave paintings, archaeologists believe the zig-zag shapes indicate an altered state of consciousness.

Lady Skollie often incorporates these Khoisan rituals into her art. We can spot the stylised Khoisan figures from cave paintings gathering in a few artworks, sometimes participating in a trans dance. She mimics the dance by creating rhythm in her art, drawing repetitive patterns. By repeating the same action over and over and over again, she enters a state of calm, a space where creativity simply flows freely.

The Khoisan have a well-known Healing Dance. It’s not only for personal healing but also for community healing. In some ways, Lady Skollie has become like a shaman for her people. Various artworks by Lady Skollie seek healing for the collective trauma of the Coloured People of South Africa.

An example of this is her exhibition In Birmingham, England, called “Weakest Link.” Bringham is where many slave chains and collars were manufactured for the African Slave Trade. In her exhibition, she drew chains, but with one link broken. One person breaks free, taking their freedom and shaping a new identity for themselves. Like a shaman, she is channelling a new way of seeing, acknowledging the past, but looking forward to shaping a better future.

Her 2023 exhibition called “Groot Gat”, which translates into ‘gaping hole’ is about the massive loss of culture felt by many black and coloured people of South Africa. Oppression, Colonialism and Apartheid left this enormous hole and gaps in Lady Skollie’s culture and history. She explains:

As a child, I would ask my elders about where we come from and how we came to be, and I would be sent from one elder to another, each saying they can’t remember. From those conversations, I would pick up pain in their voices.

The exhibition imagines an alternative reality for the Khoisan. It is about a natural sinkhole that is filled with water in the Nothern Cape of South Africa called “Boesmansgat.” Bushman’s hole. Inside, Lady Skollie imagines a deity called Dada. She has named her deity after this Khoisan artists, Coex’ae Qgam, who also goes by the name Dada. Dada sits painting massive cave paintings, luring people to jump into the hole.

The souls that perish are collected by a water girl that takes the shape of a mermaid. She draws strength from the souls.

“At the end of my Groot Gat is a surprise because it is not a dark evil place. It is actually a place where the fantasy is real, a place where being coloured /brown is not a culture that’s nipped in the bud. A place where everything has extended and evolved to a point where cave drawings are large, our identities are intact, and we know where we are coming from and where we are going.”

Lady Skollie

This work seems to draw inspiration from African Mythology. Lady Skollie’s water girls bear some similarities to Mami Wata, a water goddess revered in North Africa.

She is known for abducting people whilst they are swimming or boating. She brings them to her paradisiacal realm, which may be underwater, in the spirit world, or both. Should she allow them to leave, the travellers usually return in dry clothing and with a new spiritual understanding. These returnees often grow wealthier, more attractive, and more easygoing after the encounter.

This specific series of Lady Skollie works links to the philosophies of Afrofuturism. Afrofuturism imagines an alternative future for people of colour. While Afrofuturism is most commonly associated with science fiction, it can also encompass other speculative genres such as fantasy, alternate history, and magic realism, as seen in these works.

The artist gets emotional when speaking about the responsibility she feels towards her community. “It’s our responsibility to give other people something to resolve, and I think that’s what my work is about. Any opportunity I can give my people to resolve things that have been plaguing them, the better.”

Her work titled Good & Evil, ’n Skaans Teen die Donker (Protection Against the Dark): I Collect Them All Together Under My Arms, Lifting Us All Up Together, Up and Away From the Past. 2019. She depicts herself with long arms covering a community of many who are cocooned in her shelter.

4. Religion & Mythology

Lady Skollie often depicts Khoisan Religion in her artworks. When referring to Khoisan Religion, please remember there is considerable diversity within the different Khoisan tribes, and beliefs can vary among regions. There are, however, coherent themes and deities, but some details and symbolism may differ.

The Khoisan Creation story is unique since there was a pre-existing world before the one we know today. In the beginning, there was a magical realm hidden beneath the earth. The supreme being that created all life is known as Cagn or /Kaggen. He is known as a trickster god with both creative and mischievous qualities. He can appear in many forms, such as an Eland Bull, Snake or Caterpillar but is often depicted as a praying Mantis.

In this realm, people and animals lived in harmony; they could communicate fluently. People and animals could also shape-shift; for example, a human could take on the shape and energy of a rabbit and vice versa. Even though peace reigned supreme, Cagn had big plans for the world above. He wanted to build an even better world for his people.

So on the top layer of Earth, he started by creating a massive tree with its branches stretched out across the land. He also created the sun to provide light. He was delighted with his work and ready to show his people. So he dug a hole at the base of the trunk and started to lead the people to the new world. Excitedly, he beckoned the first man to climb up the hole and sit at its edge.

In no time, the first woman emerged too, and soon all the people gathered at the foot of the magnificent tree. They were amazed at the new world they had entered, their eyes wide with wonder.

Next, he helped the animals climb out of the hole, but some animals were so eager that they found a way to scamper up the tree trunk and all the way into the branches. To this day, these animals still live in the tree tops. Eventually, all the animals made their way out of the world above, bursting with excitement.

Cagn gathered everyone and gave them an important instruction: live together in harmony. Then he gave them a special warning. He told them never to build any fires, no matter how cold it gets or a terrible evil would befall them. They promised to obey, and Cagn left to watch over his creation secretly.

As evening approached, the sun started to sink beneath the horizon. The people and animals stood there, watching this incredible phenomenon unfold. But when the sun disappeared completely, fear crept into the hearts. Without the keen eyes of the animals, they could not see in the dark. They also became really, really cold since they didn’t have any fur.

In their desperation, one man suggested building a fire to keep warm, and they quickly kindled a cosy fire. The warmth enveloped them, and miraculously, they could see each other again. However, the fire frightened the animals, causing them to flee with anxiety to the safety of the caves.

From that day on, communication between humans and animals was severed. Form now on, man had to hunt for food, trekking over miles to find the animals. The animals and humans could also no longer shapeshift into each other’s forms. The people who where in a state of shape shifting became trapped in the animal form. Fear took over the place where friendship once thrived. It was a sad outcome of the people’s disobedience, and they deeply regretted their actions.

There are many Khoisan stories, all teaching a lesson or sharing a new insight. Now that you know the story lets get back to Lady Skollie’s art.

In this Lady Skollie artwork, Cagn speaking to the people from the sky (2018), we see /Kaggen descending to earth in the form of a snake leading his people. Here, we see Cagn as a flaming praying mantis (2018). He seems fierce and enraged, with multiple arms and gold-tipped claws, ready to strike and impale someone. In the artwork called, The Burning Bush – always good enough to make a change, small enough to doubt the change, 2020 she combined Cagn’s tree with Moses’ burning bush from the Bible. All three of these artworks seem to be about Cagn’s disapproval of the state of his people and have a central theme of leading them once again to a better place.

Lady Skollie also incorporates other symbols from Khoisan Religion, such as the moon or the night sky. One of the Khoisan stories, tell how Cagn created the moon by tossing his own shoe into the sky. The Sun is jealous of the moon and chases it across the sky with a knife, slowly carving away at it and only leaving the backbone for the children.

However, the moon has resurrection powers and is reborn every 28 days. The moon in Lady Skollie’s artworks is usually a symbol of rebirth. Lady Skollie also often paints the night sky filled with stars. In the Khoisan religion, the milky way is formed by a girl throwing fire ash into the sky. She does this so people can still see a little bit at night when the moon is carved to only a slither. There are multiple stories about how certain stars were formed in the Khoisan stories, but it is often as guidance to the people.

To the Khoisan, water also holds resurrection qualities. In one of the stories, Kaggen’s grandson is murdered by a troop of baboons. The baboons start playing ball with the grandson’s eyeball. Kaggen tricks the baboons by pretending to play with them and proceeds to steal the eyeball. He throws the eyeball into the water, and his grandson emerges alive and restored.

Yes, his grandson is a meerkat, remember the gods can still shape shift. In a different tale, Kaggen resurrects an ostrich by laying one of its feathers in a pool of water, and a baby ostrich is born. Lady Skollie also uses water as a symbol in her artwork depicting both the peril of drowning and the call to initiate a resurrection and a new beginning.

Kaggen’s most beloved creature the Eland, was also created using the ressurecting power of water. Kaggen took his son-in-law’s shoe and dropped it into a pool of water. Soon a beautiful Eland emerged. Kaggen fed it honey and rubbed its skin in it, giving it its magnificent colour.

In the Khoisan religion, the Eland holds significant cultural and spiritual importance for the Khoisan people. It is considered one of the most sacred and revered animals in their traditional beliefs and practices. Lady Skollie incorporated the Eland in her collaborative Light Sculpture installed at the Spier Wine Farm in 2022.

“A night light to calm the energy of this valley, a night light to calm historys bad vibes. A totem of memory glowing from the past but bathing the future in light. Our shadows far behind us. The Eland, the Snake, the Ostrich, the walker, A tower of what was here, not yet disturbed.”

Lady Skollie

The artwork Skaans teen die donker also incorporates Theraintropes, half Eland half man figures.

5. (Dis)harmony with nature

The Khoisan religion is characterised by a strong connection to the natural world and a deep reverence for the land, plants, animals, and ancestral spirits. It emphasises the interdependence and interconnectedness of all living things and places great importance on maintaining harmony and balance in the world. They are often lauded for their incredible knowledge of animal behaviour and the environment, especially plants.

Lady Skollie also often draws various plants and herbs, referring to her ancestor’s in-depth understanding of nature. However, by looking closely, you will quickly realise it is not in harmony with nature but in disharmony.

Here one plant is dying. This one has nails hammered into it. These sunflower stems are weaved into slave chains, and a severed flower is dripping with blood. The titles of these artworks reveal they are weeds and not nurturing medicinal plants. The one is titled “Onkruid vergaan nie”, which translates into “Weeds do not die.” This could refer to how views of coloured people have changed over the centuries and the various times they have been dispossessed of their land and housing. First, there was the Bantu Expansion then colonialism, removing them from the land, but later, during Apartheid, there was the forceful removal of the Cape Coloured community in District Six.

District Six was a thriving mixed raced community at the foot of Table Mountain in Cape Town. The Apartheid Government declared it a whites-only area and forced all the other people to move out. They sent in bulldozers to demolish everyone’s houses so that they could build a nice area for white people only. All the people of colour had to move to a new housing project on the Cape Flats. The Cape Flats was horrible sandy land and almost unhabitable.

Today the Cape Flats is one of the most violent and dangerous places in South Africa. Serious social problems include a high rate of unemployment and high levels of gang activity. To some these coloured communities are seen as a nuisance rather than an asset to society, onkruid, weed and like weed, when plucked, new seeds are sown, and it just keeps growing and flowering all over the place. Lady Skollie’s artwork is saying, not matter how many times her people are removed, plucked out or suppressed they will just keep on growing and flowering.

Conclusion

And that concludes the five ways in which Lady Skollie Honours the Khoisan people in her artworks.

I am artist Lillian Gray, and I love teaching art and art history.

Buy our Lady Skollie worksheets and art resources

We have excellent art history resources for teachers and students available right here on our website. Shop our various worksheets, class posters, class décor, exam papers here.

BUY OUR LADY SKOLLIE WORKSHEETS

Our worksheet pack includes notes and fun activities. Ideal for art students and history students to learn more about Lady Skollie

Resources

Bleek, W.H.I. and Lloyd, L.C. (2022) Specimens of bushman folklore. Higgins Press.

- !Gaunu-Tsaxau, The son of the Mantis, the Baboons and the Mantis

- The Girl of the early race who made stars

- The Great Star !Gaunu, which singing named the stars

- What the stars say and a prayer to a star

- !ko-g!Nuing-Tara, wife of the dawn’s heart star, Jupiter

- The resurrection of the ostrich

- The Khoisan Creation Story

Immanuel, B.W.H., Lloyd, L.C. and Bleek, D.F. (1924) The mantis and his friends: Bushman Folklore. Cape Town: T. Maskew Miller.

- The Mantis makes an Eland.

- The Mantis makes an Eland – Second Version.

- How the Mantis gives the bucks their colours.

Johnson, P., Bannister, A. and Wannenburgh, A. (1999) The Bushmen. Capetown: Struik.

- The Khoisan Creation Story

Parkington, John. (2002) The mantis, the eland and the hunter. Krakadouw Trust.

- Characteristics of Khoisan Cave Paintings

Parkington, John. (2003) Cederberg Rock Paintings. Follow the San. Krakadouw Trust.

- The Evolution of Khoisan Cave Paintings