No products in the basket.

Art History

South Africa’s most successful artist William Kentridge! Understanding the 17 key themes in his art.

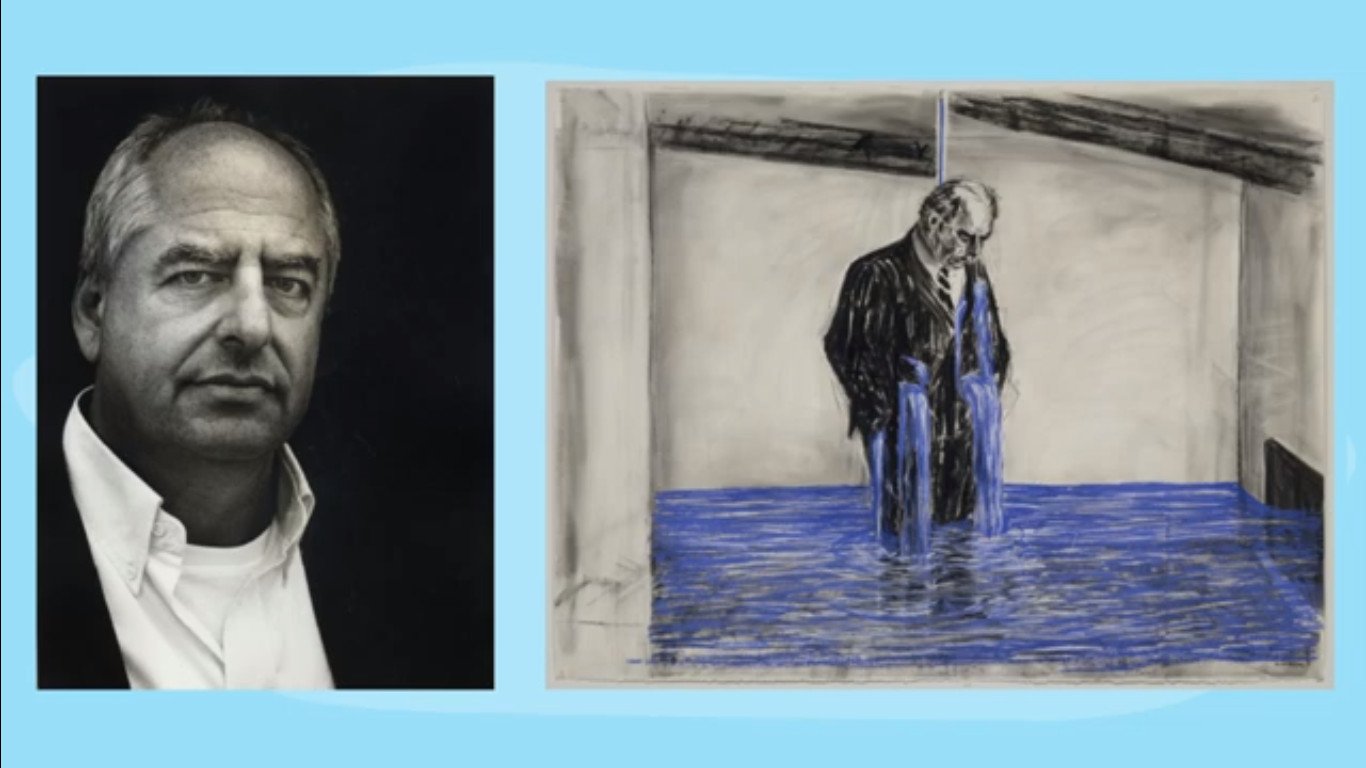

William Kentridge is a South African artist best known for his charcoal drawings, animations, bookmaking, puppetry, theatre productions, tapestries and films. He is a prolific artist that has been actively making art for over three and a half decades. In essence, working with what is a restrictive media, using only charcoal and a touch of blue or red, he has created animations of astounding depth.

World Recognition and Economic Success

The political content and unique techniques of Kentridge’s work have propelled him into the realm of South Africa’s top artists. He is South Africa’s most successful living artist and holds the record for the most expensive drawing ever sold.

Kentridge’s bold artistic vision has made him one of the world’s most sought-after artists by museums and collectors alike. His work can be found in some of the most prestigious museums globally, including the MoMA, New York, Tate Modern in London, and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago. He has even exhibited in the Louvre in Paris.

Kentridge also boasts an array of awards. Other career highlights include reaching the Time 100 in 2009. An annual list of the one hundred top people and events in the world. That same year, the exhibition was awarded First Place in the 2009 AICA (International Association of Art Critics Awards)

In 2012, Kentridge was in residence at Harvard University invited to deliver the distinguished Charles Eliot Norton lectures in early 2012.

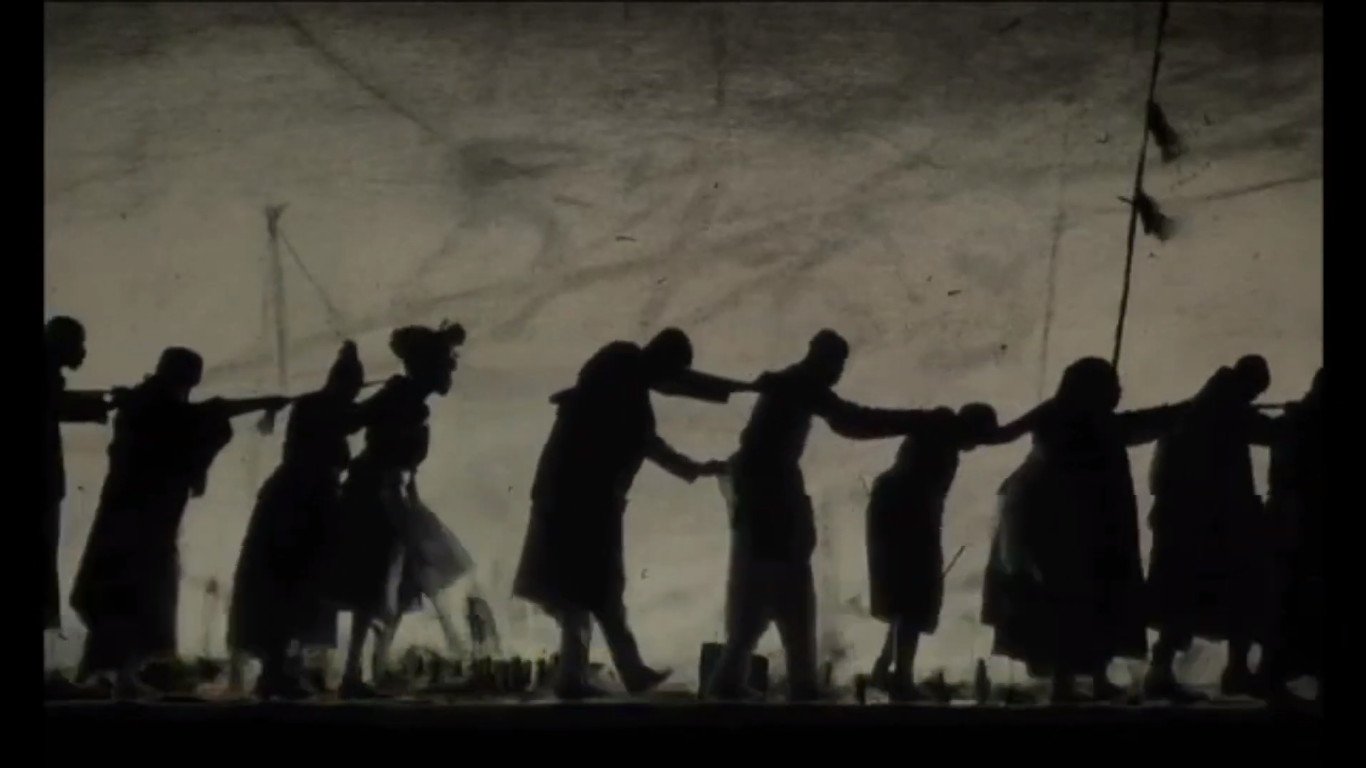

In 2001, Creative Time aired his film Shadow Procession on the N.B.C. Astrovision Panasonic screen in Times Square.

Let’s delve a little deeper into Kentridge’s life and the symbolism behind his massive collection of artworks.

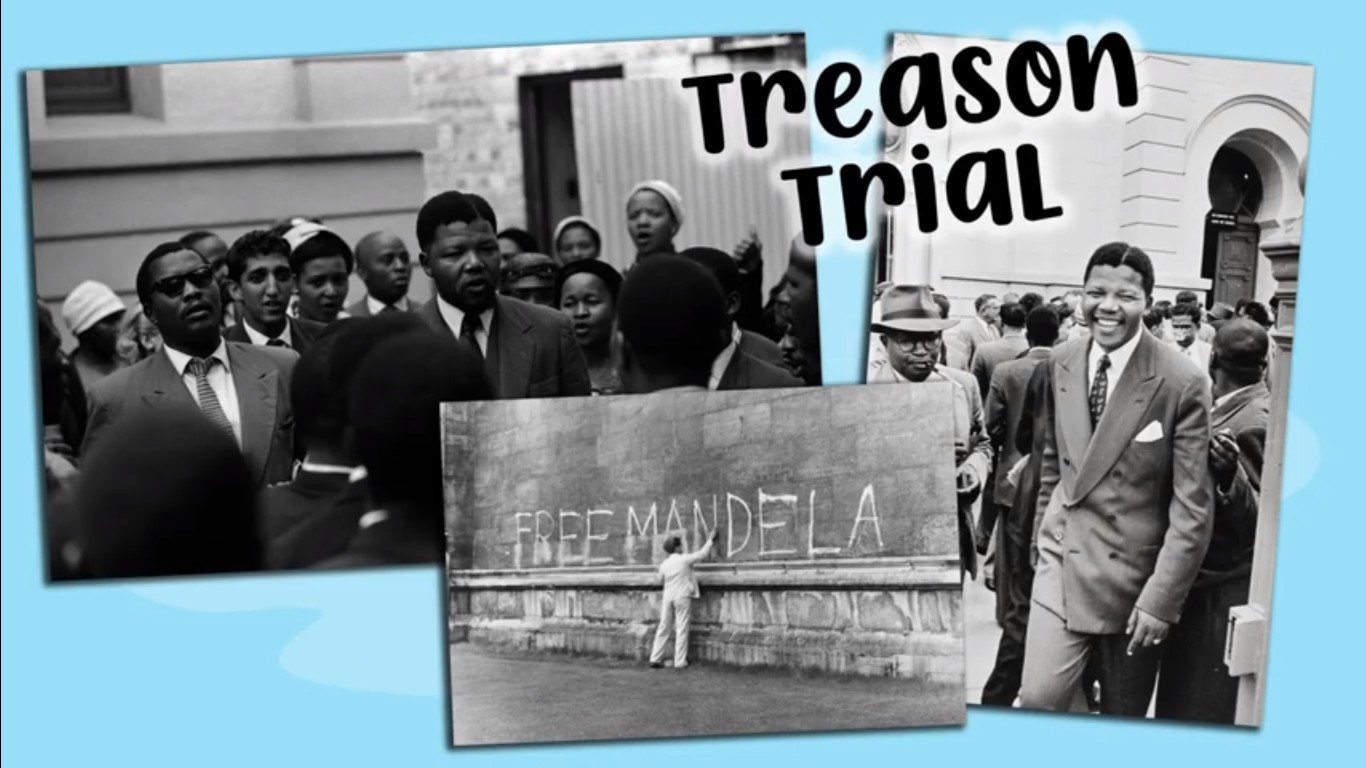

A witness to pain and suffering

Kentridge’s parents Sydney and Felicia Kentridge, were both advocates. They specialized in representing people oppressed by the Apartheid System. His father and mother played a leading role in a number of the most significant political trials in apartheid-era South Africa, including the Treason Trial of Nelson Mandela and the 1978 inquest into the death of Steve Biko. His parents’ dedication to the fight against Apartheid in South Africa would have a lasting impact on the artist, setting him apart from many of his white peers from a young age and heavily informing his work.

In 1960 Black protests against Apartheid reached a turning point when police killed 69 people in the Sharpeville Massacre. Kentridge was six years old when he was poking around in his father’s office. His eyes focused on a beautiful yellow Kodak box. It looked like a chocolate box to young little Kentridge. He was shocked and horrified when he peered inside. These were photos of the Sharpeville Massacre. His father was using it as evidence for the trial.

I was six years old, and my father was one of the lawyers for the families who had been killed in the Sharpeville massacre. I remember once coming into his study and seeing on his desk a large flat, yellow Kodak box and lifting the lid off – it looked like a chocolate box. Inside were images of a woman with her back blown off, someone with only half her head visible.

William Kentridge

This box forced Kentridge to see the atrocities that the Apartheid system created. He was no longer sheltered or innocent. Kentridge became a witness to peoples suffering and pain. A third party observer. He has spent his life and career re-examining South Africa’s recent history. This yellow box became a symbol to him of South Africa’s recent history.

When he was 9, he recalls one day driving with his grandfather. They saw a man in a ditch, and around this man were four people kicking him. Young Kentridge was shocked at adult violence. He couldn’t believe adults could be that cruel to each other.

Finding a career

Kentridge enjoyed an excellent education as a child. His parents also often read Greek Mythology and classical literature to him. He also attended art lessons and developed a love for drawing. However, with all his talents and exposure Kentridge had difficulty in finding the proper vocation.

What surprised me about studying Kentridge’s life is that he never did a degree in art. South Africa’s greatest living artist doesn’t have a degree in art? He left school and did a degree in Politics and African Studies at the University of the Witwatersrand. Then he did a diploma in Fine Arts from the Johannesburg Art Foundation.

Kentridge loved drawing, and he loved acting, but he was also drawn to politics. Kentridge dabbled with both art and acting until one day, someone said to him…

“You have to specialize! You need to decide between drawing and acting. You cannot do both. If you do both, you will remain an amateur.”

Bad advice from a friend.

After hearing this advice, he closed his art studio. He kept on hearing a small inner voice saying, “You do not have the right to be an artist.” So he sold his etching press and art supplies and set off to study mime and theatre.

After three weeks, he discovered that he wasn’t a great actor. Kentridge felt deflated and miserable. If he wasn’t an actor nor an artist, what was he? So he tried to become a filmmaker…and then he failed at that also. So he failed at painting, failed at acting, failed at filmmaking. So what was he?

At the age of 30, he went back to his love for drawing. He thought to himself, “Ok, I’ll do this until I find my real job”, and he told his friends “, I am looking for a real job. One day I will end up working for a Building Society or in a Bank.”

A good friend walked up to him and said to him;

“You understand you are now 30; no one will give you a job? You are unemployable. Stop having this illusion that you will find another life. Drown or swim but accept that you are an artist.”

A good friend of Kentridge

Finally, Kentridge realized he was All the things! He was someone that loved drawing, did theatre, made movies and loved politics and the law. He didn’t have to choose. He could be all of it. He started blurring all the boundaries between these different mediums.

In the end, I gave up saying what I was. I was someone that did drawings, theatre and films. It took me a long time to unlearn the advice I was given. My only hope was the cross-fertilization between different mediums and genres.

William Kentridge

Kentridge always says that his failures rescued him. If he was a slightly better actor, he might have ended up sticking with acting. Playing the 3rd Swordsman in the play and never the lead role. Today he is grateful that he wasn’t excellent at painting, acting and filmmaking because it ultimately led him to the fusion of genres he is known for today.

“I was fortunate to discover at a theatre school that I was so bad an actor I was reduced to an artist, and I made my peace with it.”

William Kentridge

It is easy to see his work as theatrical. Like “Black Box”, many of his works even take on the shape of a theatre. The world he creates brings together many sources and ideas. He combines voices and characters, various ways of seeing and thinking; science; art history; literature; philosophy; and linguistics; opera symphony; dance and performance. All combined and complement each other in unpredictable and exciting ways.

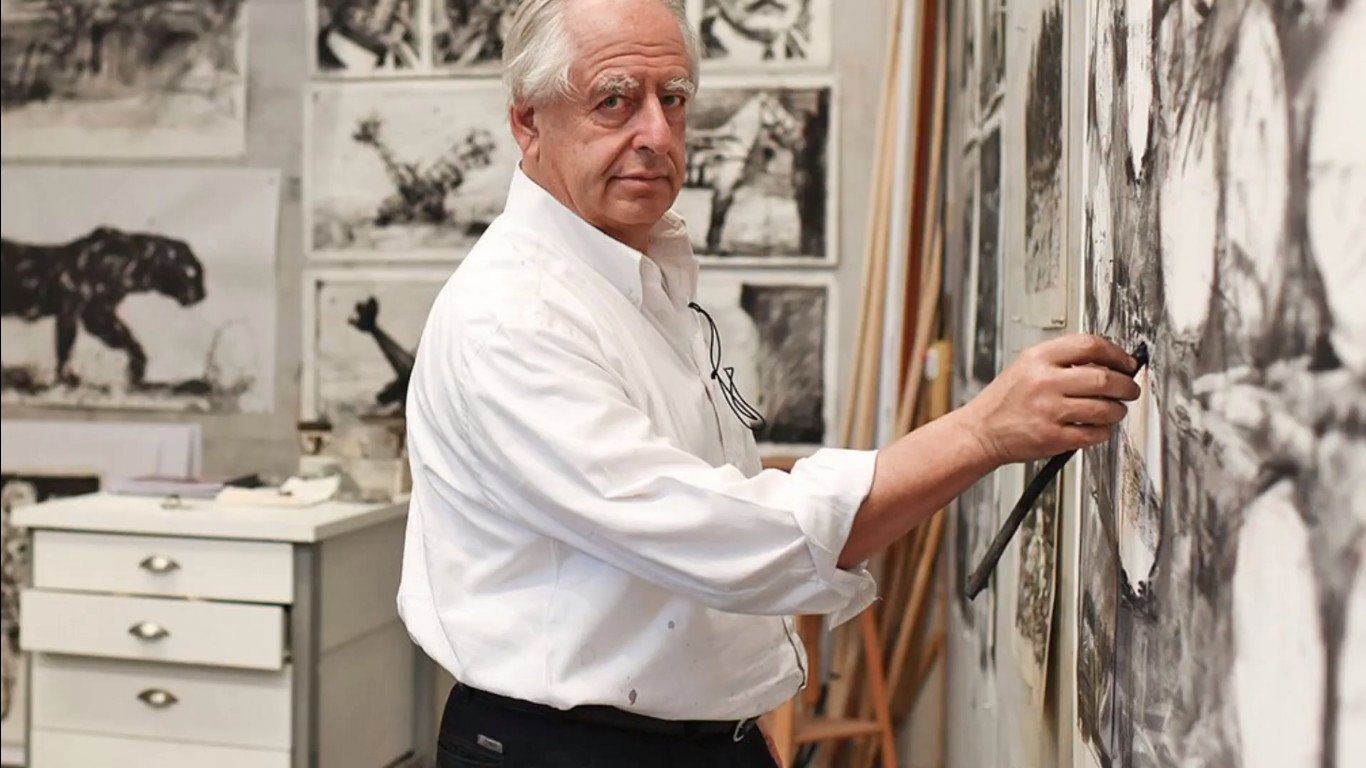

Developing a unique technique

Kentridge has developed a unique method by combining all his interests. It is his famous charcoal animations. In the studio, Kentridge puts a large sheet of paper on the wall. He then places a camera four paces away. He draws on the sheet of paper, walks to the camera and takes a photo. Click. He walks back to the paper, makes a slight change to the drawing, erasing and adding to the image.

He walks back to the camera, taking another photo. Click. And so he repeats this loop over and over, painstakingly working on the same piece of paper. He then edits all the photos in sequence and creates a moving image. Each photo of the drawing receives a quarter of a second to two seconds’ screen time. A single drawing is altered and filmed this way until the end of a scene.

This process is unique since traditional animations are usually done with one drawing per paper, creating thousands of drawings. Commercial animations display 24 images per second. Kentridge doesn’t use thousands of drawings like they would in commercial animation. He only uses 20 – 40 images. This method is primitive and crude and gives his animation movies a jagged sense of movement, a vintage, grainy feeling, and creates uneasiness. Kentridge also draws on one sheet of paper.

He can do up to 100 alterations per page. He can do this because charcoal erases easily. He can change it as quickly as he can think. It takes several weeks to make a minute and ten months to make a 9min film. His technique is more about making a drawing than a film. Kentridge then proceeds to add music to the animation and, in some cases, dialogue.

A question I often get asked when teaching a lesson on Kentridge is, “If he makes movies and they are mainly free to watch, then how does he make money with his art?” What does he sell in the galleries? The last alteration of an image marks the end of a specific scene in his films, not the end of the film, but rather the end of that specific scene. He then takes this last drawing, frames it and displays it in the gallery with the film as finished art pieces.

Developing a Visual Language

Kentridge has a cohesive visual language that he has developed over the years. We can almost instantly recognize a ‘William Kentridge artwork’.

Suppose one artwork is a word. A series of artworks, such as an exhibition, is a sentence. Then a body of work over the years would be an essay or a book. This, to me, is a lovely analogy and so relevant to Kentridge’s artworks. To truly understand Kentridge’s works, you need to look at his entire body of work over three decades. His work is filled with complex narratives and layers and layers of meaning. He uses metaphors, symbols, references to famous artworks, philosophy, and politics in his work.

Let’s look at key themes in his works and how he developed his visual language.

- A Cohesive colour scheme

- The Surface has Memory

- Symbols of Communication and Navigation

- Duality in both man and society

- Metamorphosis

- Technologies of Looking

- Finding Meaning & Thought Process

- Repeating Characters

- The Landscape – Johannesburg

- Water as a symbol

- The forgetfulness of the landscape

- Wild Beasts – Animals as symbols

- The Rhino as a symbol

- The Concept of Time

- Famous Paintings Referenced in his works

- Written Text

- Theatre

1. A cohesive colour scheme

Kentridge’s artworks are predominantly black and white, done in charcoal or Indian ink with a Chinese Calligraphy brush. He also sometimes plays with inverted images where he makes the background black and uses white lines. The stark contrast between black and white can be seen as the contrast between the races in South Africa. South African artist Dumile Feni has influenced his work. Feni is known for both his drawings and paintings, which often depicted the struggle against Apartheid in South Africa. Namibian great artist John Muafangejo also influenced Kentridge with his woodcut prints.

Red symbolizes blood, wounds, death, and violence. In “Felix in Exile,” red colour is used extensively in Nandi’s depictions of landscape. The places where the corpses lay, as well as their wounds, were marked clearly in red. For example, when Nandi was shot down on the ground, the blue water flowing down from the faucet turned red. It is a declaration of Nandi’s death. The dark red blood flowing out from the old wounds of the unknown corpse is a silent narrative of South Africa’s violent history. Blue is associated with peace, waiting, hope, retrospection, and sorrowfulness. Bluewater can also symbolize redemption and hope.

2. The surface has Memory

A key aspect of Kentridge’s work is that Matter has Memory. Even though charcoal is easy to erase, you can never fully erase it. Charcoal residue gets lodged into the fibres of the page, leaving smudges and ghost images. The filming process records the changes on the drawing, but the streaks that remain keep the history of the drawing. It creates a sense of fading memory or the passing of time. This toys with the idea how we can never really erase the past. As humans, we will always be haunted by the past.

It also symbolizes how a landscape can absorb a historical event, only leaving vague traces. The ghost images are very relevant to South Africa’s history. Of how the Apartheid Regime tried to erase and hide the violence of Apartheid but ultimately failed. It brings to mind George Santayana’s often quoted phrase: “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

The process can also refer to the unreliability of our memories. Each time we recall a memory, we view it with our modern lenses and slightly alter and change the memory. Our memories are inconsistent, fragile and unreliable. Then there is the transformation into “The New South Africa.” which has within it the ideas of painting over the old, of disremembering.

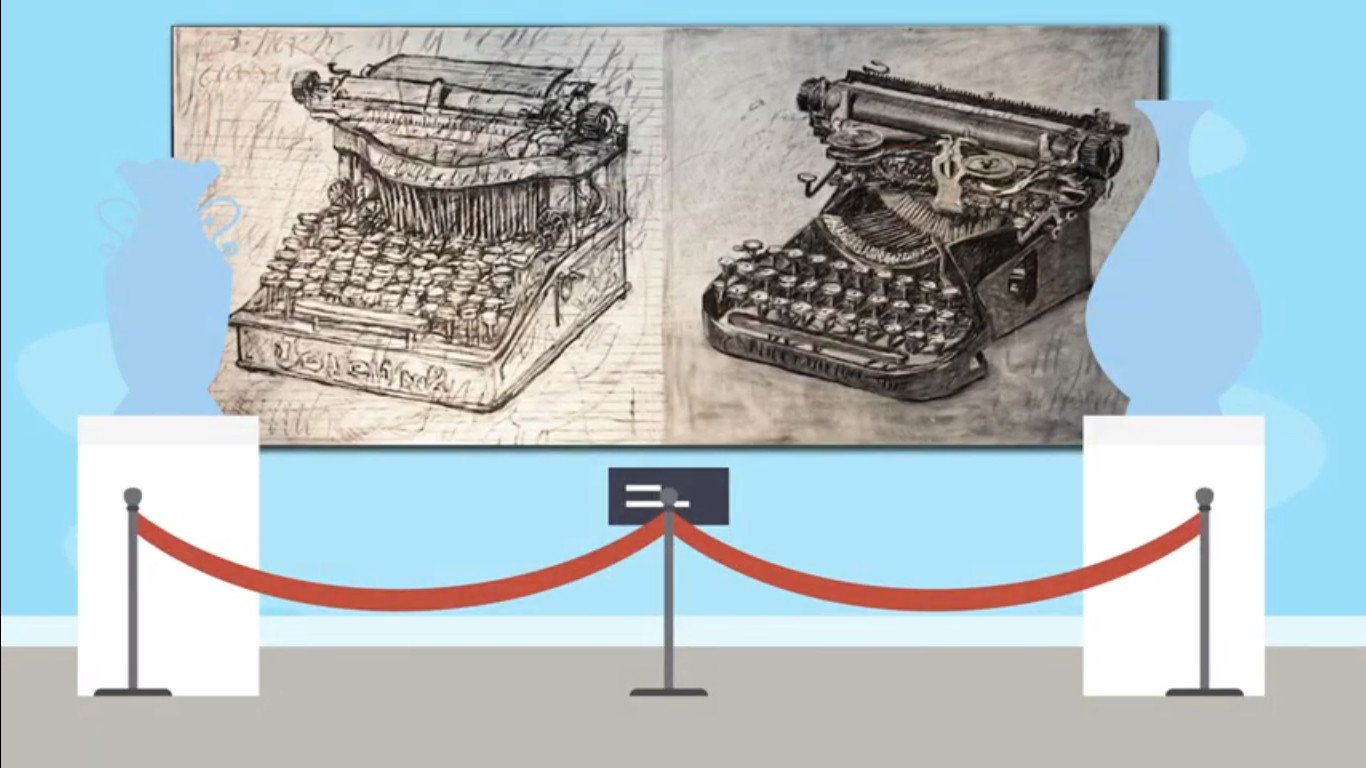

3. Symbols of Communication and Navigation

Kentridge uses symbols as a part of his visual language. He uses the same symbols repeatedly throughout his various artworks. The megaphone that often appears as part of his iconography was inspired by seeing Lenin using a megaphone. A megaphone is also an object that has become iconic in resistance art images. In Kentridge’s work, the megaphone may stand as a symbol of faceless power and dictatorship or may simply represent the artist’s voice.

Other examples are Communication Symbols: Recurring symbols in Kentridge’s artworks and films are devices used to communicate, convey a message or play music with. These include objects such as a megaphone, typewriter, telephone, telegram, morse code, overhead power lines, a film camera, newspapers, billboards, books, metronomes, and gramophones.

Navigation Symbols: Kentridge is also fond of items used in navigation. These include the sextet, telescope, leadline, maps, stars, compass, quadrant, and astrolabe.

4. Duality in both man and society

Another critical aspect of Kentridge’s work is duality. Kentridge’s entire life is filled with contradictions. He has spent 40 years under Apartheid Rule and almost 30 years without it. He often plays with the dark side and light side of life—the duality of society in Apartheid South Africa. But Kentridge delves deeper and shows the duality within each of us, our dark side and light side.

Here he plays with the duality of the artist—the artist as the creator and the artist as the viewer. As artists, we have both inside of us. The part of us that creates the work and the part that stands back and says, “Who is the idiot that drew that?” The artist viewer is always disappointed with what the maker has done.

5. Metamorphosis

Animation literally means to bring to life by adding movement. Kentridge is not only fond of movement but loves Metamorphosis, changing one object into something completely different. He uses metamorphosis to connect different events, plots and images, which joins other scenes of time and space.

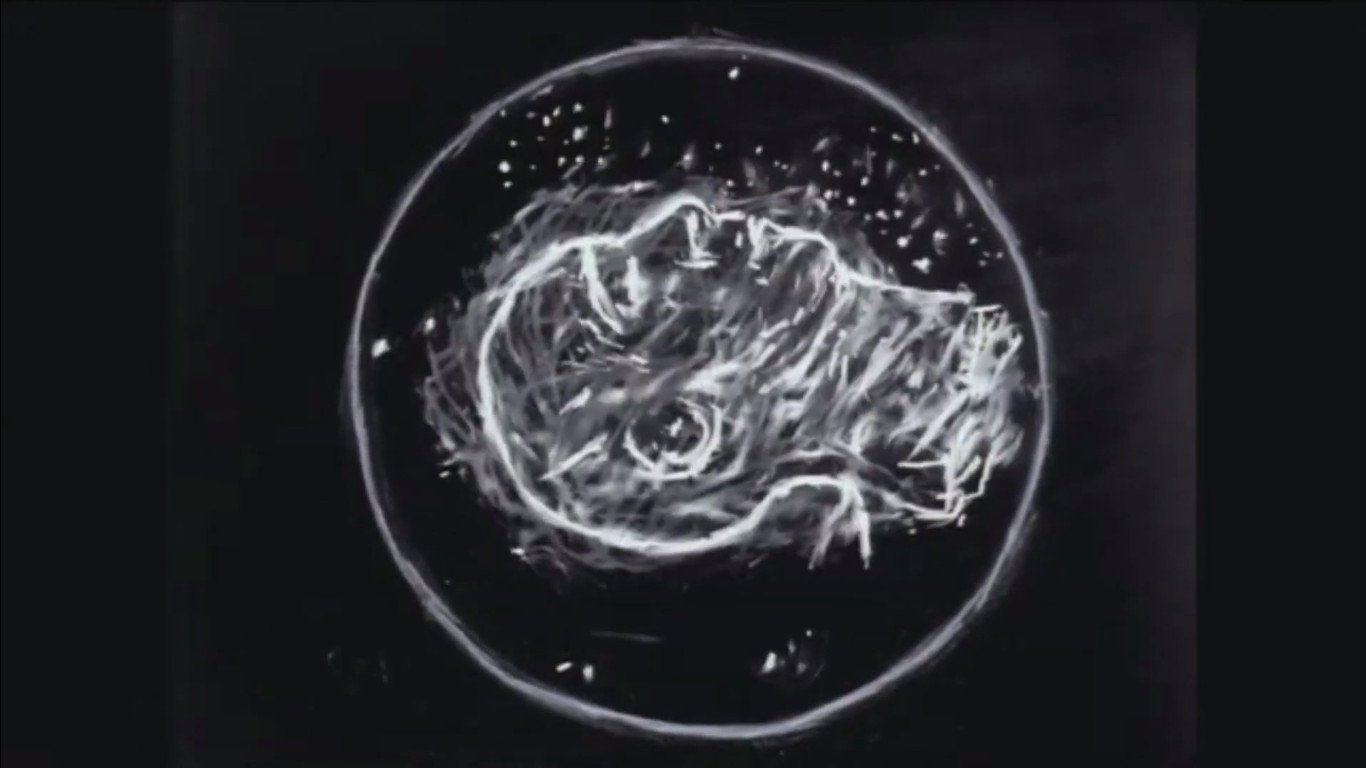

6. Technologies of Looking

Because Kentridge studies theatre and filmmaking, he has a love for the history of film. This has led him to a passion for the Technologies of Looking. Technology that is mostly obsolete today. If we understand how the brains and the eyes work together to create a sense of depth, we can trick the eyes. We can create an illusion of movement and depth that isn’t truly there. Devices that play with our perception of movement and depth are Pre-Cinematics tools.

The stereoscope, the Phenakistoscope, the zoetrope, the anamorphic mirror, and the Claude glass. These are all machines for creating illusions and are often referenced in Kentridge’s work. Kentridge also uses other objects used for viewing, like the X-ray, the M.R.I., and the cat scan. All of these devices refer to our different ways of seeing. We all look at the world differently. We all have glasses with which we view the world. They also offer the artist different ways to represent the world around him to us.

7. Finding Meaning & Thought Process

Kentridge is fascinated by how humans find meaning, develop understanding, and our general thought process. He loved depicting these as tree structures. He avoids too much structure in his work and enjoys creating freely. Therefore he does not work with a storyboard or script. Instead, a film or an artwork usually starts with a deep desire to draw. He will then start drawing and develop ideas as he walks back and forth between the camera and the paper.

Constantly changing ideas and trusting the process of creating, discovering what the next drawing will be by following the natural flow of his creativity. He says this process developed because he cannot write a story and develop a script, but it also mimics how we as humans learn in the real world. We have experiences, and then we take these fragments and make sense of the world around us.

We are not given a set of instructions on how to live life. Instead, it is a process of unfolding, a process of discovery. Life is filled with ambiguity, contradictions, uncertain endings, uncompleted movements, and so are Kentridge’s art and films. Uncertainty is key. Uncertainty is much closer to how the world is. Kentridge’s works often create a restless, uneasy feeling in the viewer and often depict uncomfortable situations. His artwork is about finding meaning in a world of uncertainty and change.

8. Repeating Characters

There are two main characters who appear in most of the films: Soho Eckstein a Johannesburg industrialist and Felix Teitelbaum, who is the sensitive poetic type and an artist. While Soho and Felix are drawn as separate characters, they represent different sides of the same person. Many of the characters in Kentridge’s films become symbolic representations. Soho Eckstein symbolize an Apartheid vision of South Africa and the darker side in us all. Nandi represents the poor and oppressed.

9. The Landscape – Johannesburg

Kentridge’s birthplace, Johannesburg, plays a crucial role in his artwork. It becomes one of the key characters in his films. He places all his symbols and characters inside the Johannesburg landscape. Kentridge has lived in Johannesburg all his life. Johannesburg is a strange, unnatural city. The city lacks a geographic marker. It has no sea, mountains, nor big rivers or water bodies, yet it is one of the largest cities in Africa and South Africa’s largest city.

The city has a prehistoric history. The Cradle of Humankind is home to 40% of the planet’s human fossils, making it one of the richest archaeological sites in the world with layers and layers of history. Fast forward, and not a lot has happened since in this particular landscape. The actual city was only formed in 1886 when they discovered gold. It attracted hundreds of diggers and fortune-seekers. For the first 30 years, it was the fastest growing city in the world.

It’s important to realize that the design of Apartheid’s had an economic incentive. The white Afrikaners needed cheap labour for mines. This created an interesting dynamic in the black culture where families would often live in their homeland; for example, the Transkei and the father had to leave to go and live in Johannesburg to get work in the mines. Miners lived in hostels with poor sanitation and appalling living conditions.

As the miners dug up the earth, minecarts dumped it above ground, forming yellow hills. The yellow colour was from the cyanide in the ground. This created a very unnatural landscape, and dust storms started to plague the rich Rand Lords. They made it their mission to plant trees in Johannesburg and create the rich leafy suburbs. Today Johannesburg is the world’s largest man-made forest with over 10 million trees.

The suburbs are leafy green but the land just outside Johannesburg is almost inhospitable. The end of the suburb marks the end of irrigation and privilege. This creates a stark contrast between the wealthy and the poor. Johannesburg thus represents an unnatural life to Kentridge.

He is constantly aware that the city is outside of nature. The natural vegetation of Johannesburg was grasslands known as the Highveld. The highveld grasslands that have remained are burnt once a year in the dry season to prepare the land for new growth. The scorched earth becomes a charcoal drawing in itself.

Kentridge often plays with the dualities Johannesburg represents in his artwork. He portrays the picturesque state of living that white people enjoyed during Apartheid and the oppressive militant place it was for black people. He constantly plays with the city as a place where the duality of man is exposed.

10. Water as symbol

This brings me to the theme of water in Kentridge’s work. Water is often seen in taps, basins, baths, washing, rinsing, shaving and flooding in Kentridge’s work. This is also closely linked to Johannesburg. Johannesburg has no water above ground but too much water below ground. When mining started, they had to get rid of the water filling the mine shafts and continuously pumped it out.

These created sinus like cavities in the earth which caused the land to become unstable. It often created sinkholes and minor shakes. Kentridge recalls teacups shaking in their house and sinkholes forming in the roads right before him as a child. He sees this as a message from down below.

While white people lived in luxury above ground, armies of miners were suffering and working below ground. The tremors can be seen as symptoms of an unnatural relationship with nature and the abnormal segregation between different races. Water becomes both a wish and a threat – a wish to irrigate the suburbs and a threat to the mines and the stability of the situation and landscape.

11. The forgetfulness of the landscape

Johannesburg used to be surrounded by mine dumps. But lately, all the golden hills have slowly vanished. This is due to a new technology that allowed mining companies to rework the ground that was dumped and extract even more gold from it. Slowly they extracted the gold from the dumps and tossed the ground back down the old mine shafts. It fascinated Kentridge how the landscape changes over time. He says that the landscape is not a reliable witness to history.

For example, when we pass a specific area where a major historical battle occurred, we can hardly see any traces of the atrocities that occurred there. Maybe where there is a mass grave, the trees will be slightly shorter than other trees surrounding them. We need to dig up the landscape for clues and analyze the layers to see the history of a place. He often plays with the idea that the land can cover and erase the past in his artworks and films.

12. Wild Beasts – animals as symbols

Kentridge often uses various wild beasts in his artworks. Such as the Hyena, the panther, the Cheetah, the warthog and the rhino.

The symbolism of hyenas in South Africa is associated with evil, dark spirits and mischief. It became a prominent symbol in Resistance art in South Africa, as symbols of repression and oppression, and often stood in for oppressive authorities.

13. The symbolism of the rhino

An animal Kentridge is fascinated explicitly by is the rhino. The rhino feels more like an ancient dinosaur than a contemporary mammal. He is attracted to the sheer mass and the strength of the rhino. Despite its weight it has freedom of movement, gracefulness and playfulness. But the fascination with the rhino and symbolism goes deeper. Kentridge sees the rhino as a symbol of the destruction caused by colonialism. It also depicts ignorance towards Africa and represents ‘The Other.’

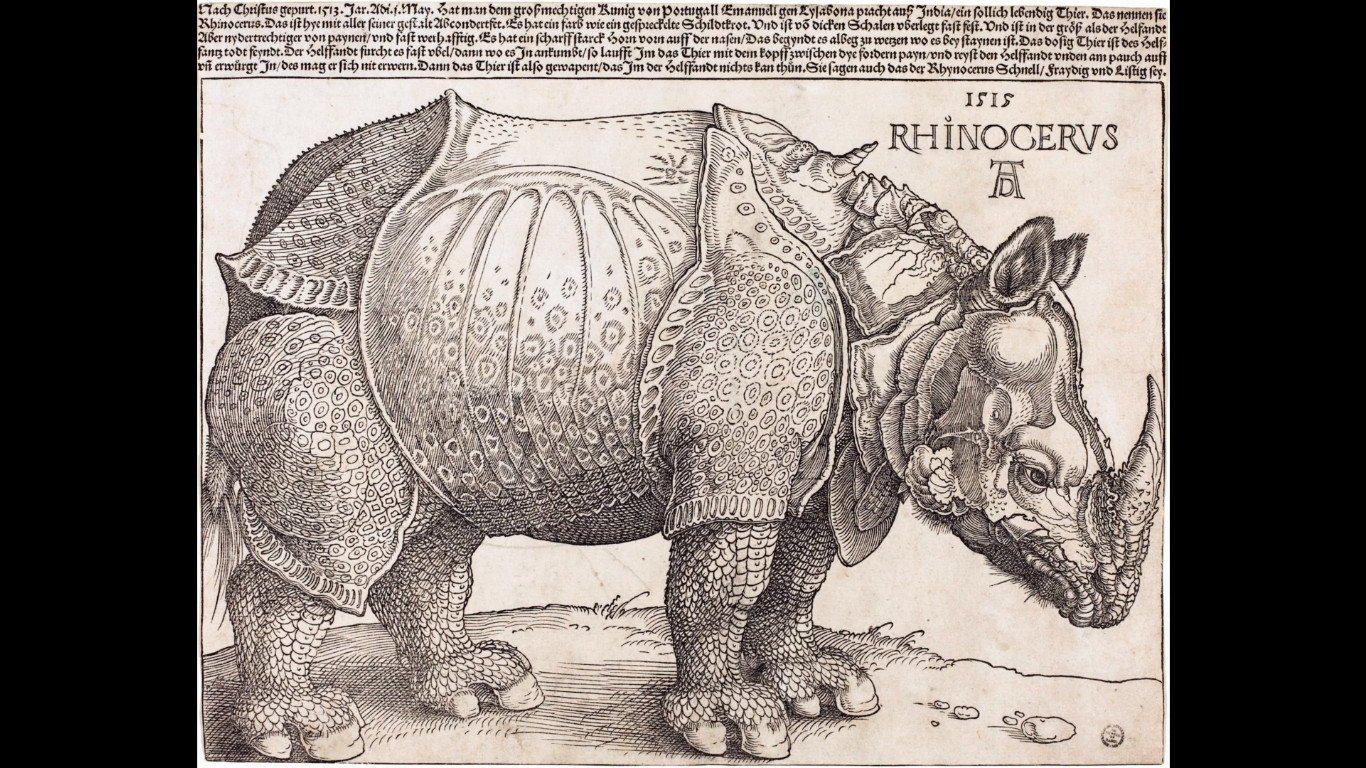

Two artworks have really influenced the meaning of the Rhino behind Kentridge’s work. One is an Albrecht Dürer woodcut print made in 1515. Pietro Longhi, Clara the rhinoceros painted in 1751.

In short Dürer has never seen a rhino in real life and created this image based on what others have seen.

The rhinoceros was sent l as a gift for Pope Leo X. While carrying the rhinoceros from Portugal to Italy; the ship was lost in a storm. As a record of the gift, Durer was asked to make an image of the drowned animal. He was reduced to making an image based on reports of others who had seen the rhinoceros. Dürer’s woodcut is not an entirely accurate representation of a rhinoceros.

He depicts an animal with hard armour-like plates with rivets holding them together at the edges. The rhino has an additional horn and scaly legs. None of these features is present in a real rhinoceros. Despite its anatomical inaccuracies, Dürer’s woodcut became very popular in Europe and was copied many times in the following three centuries.

Westerners regarded it as an accurate representation of a rhinoceros into the late 18th century. Eventually, it was supplanted by more realistic drawings and paintings, particularly Clara the rhinoceros by Pietro Longhi, 1751.

In Pietro Longhi’s painting of a rhinoceros in 1751, we see the rhinoceros at a carnival in Venice. Now, this rhinoceros was Clara, a celebrated rhinoceros that was taken on a tour of Europe between 1741 and 1751. The picture is strange indeed.

We see five men and two women, and a child observing the rhino. The horn is cut off and held by one of the men in the front. The power of the rhino is transferred from the rhino to this man. By naming the Rhino Clara, she sounds like a family member, yet there is a barrier between the people and the beast.

Because of these two artworks, the Rhino to Kentridge symbolizes Europe’s misunderstanding of Africa. It also illustrates how Europe has taken Africa’s power and treasures. The rhino also represents ‘The Other’. We are both attracted and repelled by the rhino’s otherness.

Today Rhinoceros are almost extinct because man still covet their power. The compressed hair of its horn is ground up to make aphrodisiacs and other medicines. Armed gangs with AK47’s and axes hunt rhinos and sell them to the Asian market. Man’s obsession for power will stop at nothing; even possible extinction is not sufficient warning.

14. Concept of time

Kentridge often plays with the concept of time in his work. Back in 1850, when photography was invented, the process was slow. A photo’s slow development times caused sitters to sit still for a long time and not move (Don’t smile) to capture their image. The photography becomes thick with time. Kentridge loves referencing this in his works, the accretion of time.

He adds layers and layers to one drawing to make it thick with time. By adding time to his drawings, he creates movement and life. When he holds a roll of film, he is holding a certain amount of time.

Kentridge often also toys with the reversal of time in his films. When he films himself throwing books around in his studio, it becomes an act of chaos. When he plays that same footage in reverse, chaos becomes order.

15. Referencing Famous Paintings in his own works

Kentridge also often makes reference to famous paintings in his work. These include Goya, Poussin, Turner, Watteau and Renoir. He has particularly been inspired by Goya’s ‘3rd of May’, Giotto’s ‘Massacre of the innocence‘, and Titian’s ‘Flaying of Marsyas‘. We can see how these works influenced Kentridge by the way he also depicts his victims of violence.

He draws stacked bodies in bunks underground in Mine 1991 and murdered bodies and fragments of bodies in Felix in Exile 1994. Kentridge’s most famous reference to a famous painting is his Triptych The Boating Party – 1985, based on Renoir’s painting of a similar name. The wealthy are unphased by the violence surrounding them. Their oblivious nature causes havoc. This artwork is seen as one of the most severe comments on the state of South Africa during Apartheid.

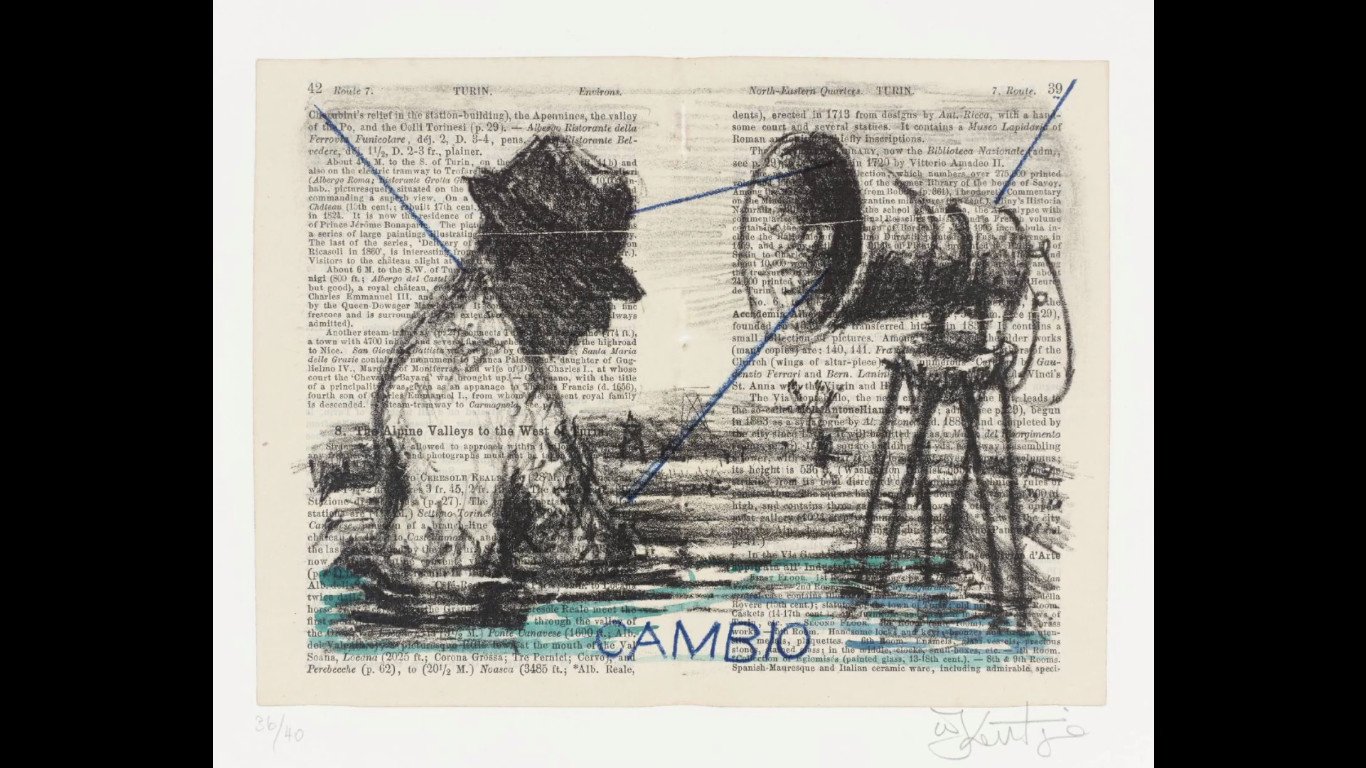

16. Written Text

Ketridge also often combines written text into his artworks. He often prints or paints directly onto discarded pages of text. He is also known for turning old books into sketchbooks. He has been influenced by the Dada Art Movement and how they incorporated text and automatic writing into their artworks and performances.

17. Theatre

The theater has a massive influence on Kentridge’s work. He is often combining art on stage backdrops, inserting actors into his artworks, or dressing actors as art pieces. Some of his artworks take the shape of an actual little mini-theater that he builds and film and his studio.

That concludes some of the major themes in Kentridge’s artworks. Let’s move on to the various phases of Kentridge’s Art Career.

The various phases of his art career.

Kentridge has a long art career spanning over three decades. His work is generally divided into two parts. All work done prior to 1994, is classified as Resistance Art. All work done after 1994 is classified as Multi-Media or New Media Art.

1994 is significant because it marked the end of Apartheid. Kentridge’s early drawings and films were influenced by the brutal society that resulted from the Apartheid Regime. In 1962 Nelson Mandela was arrested and sentenced to life imprisonment. In 1976 more than 600 students were killed in the Sharpeville Massacre. 1990 Nelson Mandela was released from prison, and in 1994 Nelson Mandela was inaugurated as President of South Africa. This marked the beginning of New South Africa.

Why is Kentridges artworks so imporant and why should we study them today?

Kentridge is one of the most thoughtful and engaging artists of his generation. Equally skilled at animation, drawing, sculpture, performance, stage design and bookmaking, among many other practices. Only a handful of artists in a lifetime whose work stops you dead in your tracks and makes you think and feel differently. His work speaks to a universal audience eventhoug he addresses complex themes specific to South Africa’s racial discrimination and Apartheid history.

Kentridge’s work dared to underscore the essential ways in which biography and history, national identity and colonialism, the traumas of survival could be investigated through the visual arts. His unflinching examination of himself and his country, of the structures of power and resistance, and the racial and ethnic tensions that have defined and plagued South Africa, not to mention the rest of the African continent, are as compelling as they are fraught with emotional and psychological tension.

Due to the complicated narratives and layers of meanings in Kentridge’s artworks, we have decided to extend this video by adding two additional videos. Please stay tuned to watch an in-depth analysis of Kentridge’s artworks done prior to 1994. This is followed by a video discussing his artworks done after 1994.

Make sure to watch the video on Contemporary South African Artist, Mary Sibande as well.

Be sure to check out our blog for more interesting artists.