Art History

5 Artworks by South African Artist Lady Skollie you should know.

Hey there, art enthusiasts! I’m artist Lillian Gray, and today I’ve got something exciting to share with you. Get ready to meet the vibrant South African artist known as Lady Skollie!

A word of caution due to the sexual nature, violence and dark humour of some of these artworks, we have created this video for 16-year-olds and up. We also have a PG video on Lady Skollie you can watch here.

Oh, and by the way, I’ve got some awesome worksheets related to Lady Skollie available on our TpT Store. They’re designed for different ages and are loads of fun to do, so make sure to check them out!

Introduction

Lady Skollie is a contemporary artist known for her thought-provoking artwork. She is a versatile and multi-disciplinary artist, adept at expressing her vision through a diverse range of mediums. Her repertoire includes painting, drawing, printmaking, and performance art. She often incorporates elements of sexuality, gender, desire and power dynamics. She loves challenging societal norms and conventions.

Her work is easily recognisable with its fusion of Khoisan drawings combined with vivid colours, intricate patterns, and bold lines, creating visually striking and engaging compositions. She draws inspiration from her personal experiences, as well as South African history, politics, social issues and her Khoisan Heritage.

She was born in 1987 in Cape Town, South Africa, as Laura Windvogel. Growing up in the new South Africa, in the Cape Coloured community, she was eager to understand what being coloured truly meant.

In South Africa we differentiate between black people and coloured people. In America, all these people would be classified as black, but not in SA. This is because during Apartheid people were separated into four different racial classes. White, Coloured, Black and Asian.

Each class had different rules and regulations and different experiences under the oppressive apartheid regime. So we still distinguish between the two.

Over the years, she crafted her moniker Lady Skollie, her alter-ego, as a place where femininity and masculinity meet. The name is a complete oxymoron. Lady refers to European conventions, especially the expectations placed on women in British society. Skollie is a word used to describe a male person of mixed race in South Africa who is an outcast, an uncouth thief or a thug.

She wants you to think of Lady Skollie as “that dirty auntie Skollie who says what you’ve been thinking but would never admit to…”

This combination of Lady and Skollie refers to the tension and struggles that shaped the Cape Coloured Community of South Africa throughout its history.

This video will touch on this complex history so that you can truly understand her art. Buckle up and prepare yourself because I am about to unveil the top five mind-blowing masterpieces by Lady Skollie that you absolutely cannot miss!

1. They’ll suck you dry, beware. 2016

At first glance, we see an orange woman hunching over, with four breasts, a papaya for her head and a broken chain around her neck under a starry night on a barren land. What on earth is going on here? I am glad you asked; let me explain.

This piece is about Krotoa (1643 -1673). Krotoa was a KhoiKhoi girl who suffered at Colonialists’ hands during the Cape Colony’s founding. She was the niece of Harry die Strandloper (the beach walker) chief Autshumao who often traded livestock with the Dutch for various goods. At the mere age of 10, Krotoa was sent to go live in the household of Jan van Riebeeck, the first governor of the Cape Colon, to train as a translator for the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC).

During her teenage years, Krotoa dedicated herself to learning Dutch and Portuguese and began working as an interpreter for the VOC. Her linguistic skills allowed her to swiftly establish herself as a shrewd and capable business partner to the Dutch. At the time of her death, Krotoa spoke four European languages fluently. In this role, she occupied a truly exceptional position as she skillfully navigated the cultural divide between the indigenous people and the European colonisers.

She became a woman caught up in man’s world, sitting in council with male officials and military officers. At the height of her career as an interpreter, Krotoa held the belief that the presence of the Dutch could bring mutual benefits to both sides. However, her role as a mediator between her tribe’s needs and the expansion of the colony placed her in a constant state of conflict. Nevertheless, she emerged as a highly valued peace negotiator during times of war. Krotoa personified the genuine state of being suspended between two cultures moving back and forth between two cultures.

Tragically Krotoa became a pawn in this male-dominated world. At first, she was under the protection of Governor Jan van Riebeeck. The circumstances surrounding Krotoa’s entrance into Jan van Riebeeck’s household have been the subject of various accounts. One version suggests that she was forcibly taken as a child, although no concrete evidence substantiates this claim. However, she did attempt to run away on multiple occasions but was always found and brought back to the fort. It could also be that Krotoa was a pawn in one of her uncle’s treaty deals with the Dutch.

It is possible that she joined as a companion to Jan van Riebeeck’s children or as a servant to his wife. Krotoa was never completely clothed like a European but rather wore clothes usually assigned to slaves. A symbol of being accepted in the social society of the Dutch VOC was baptism. She was only baptised 3 days before Jan van Riebeeck left the Cape and was given her new Christian name, Eva.

The late baptism indicates that she was never a part of his family. Several authors and historians speculate that her living conditions likely involved sexual abuse, based on the affectionate tone Jan van Riebeeck displayed towards her in his journals. mention her name over 200 times in 65 entries in the journal.

There have been speculations of Jan van Riebeeck’s rape of Krotoa, there is no definitive proof of such events. The problem with interpreting Krotoa’s history is that we only have written accounts by the perpetrator and not the victim. Together with this evidence, we can study the Zetigeist and then only speculate what life was like for Krotoa. The establishment of colonies came with a certain culture of violence. Once the Cape Castle was completed, it had a dungeon and torture chamber. It was a society that practised slavery; they bought and sold people.

In her article titled “Was Eva raped? An exercise in speculative history,” Yvette Abrahams argues that slavery and rape were commonly employed tools of exerting dominance during colonialism.

Krotoa birthed her first child at the mere age of 15 when she was still under Jan van Riebeeck’s protection. There is much speculation as to who the father of this first child was. The VOC blamed it on a French lieutenant passing through on his travels. Later at the age of 17, Krotoa birthed her second child in the fort. This could indicate abuse as a female teen in this overwhelmingly male environment or suggest a secret love.

Moreover, Abrahams demonstrates how Krotoa exhibited several signs of Rape Trauma Syndrome later in her life. Heritage activist Van Anderen supports the belief that Krotoa endured abuse and rape, possibly at the hands of multiple Dutch officials, and does not discount the possibility of van Riebeeck’s involvement in these acts.

Once van Riebeeck left the cape, the new Governor had no use for Krotoa since the colony was firmly established by then. She lost her protected status. Krotoa, now known as Eva married Pieter van Meerhof, and her name was officially changed to Eva van Meerhof. She was the first KhoiKhoi to be baptised and had a Christian marriage.

To the Dutch, she was seen as a cultural bridge between the Dutch and the indigenous KhoiKhoi, but it created conflict with her own tribe and was met with disapproval. Unfortunately, Krotoa’s husband was murdered on an expedition, and she was left with their 3 children. She has now lost her male protection once again, and her life took a tragic turn.

Eva, spiralled into alcoholism and chose to leave the fort, seeking refuge in the native KhoiKhoi “kraal.” As time passed, her relationships with both the Dutch and the Khoikhoi became so strained that she became an outsider in both societies. Regrettably, she was imprisoned for immoral behaviour and subsequently banished to Robben Island. Tragically, Krotoa lost custody of her children.

This woman, with a brilliant mind and aptitude for languages and politics, is said to fall into prostitution. Prostitution was a part of most port cities already in the 1600s. Krotoa eventually dies at the mere age of 31, drinking herself to death. By this time, she had birthed eight children in total, of whom three Died in infancy.

In retrospect, her Dutch name, Eva, meaning “first woman,” ironically encapsulates her experiences under colonialism, which were shared by countless Khoisan women throughout history.

Krotoa has become a symbol of resilience, cultural hybridity, and struggle for identity in the context of South Africa’s colonial past.

Let’s delve into the analysis of Lady Skollie’s artwork once again. It is evident that the drawing style draws inspiration from Khoisan Rock paintings, characterised by elongated arms, a side view perspective, prominent buttocks, and exposed breasts. The vibrant orange hue also recalls the iron-rich pigments utilised by the Khoisan.

Including a papaya head accompanied by four breasts symbolises fertility and pays homage to Krotoa’s significant role as a mother figure of the nation. Following Krotoa’s banishment, Elizabeth Van Opdorp, Jan van Riebeeck’s niece, adopted some of Krotoa’s children. The youngest daughter, Pieternella Meerhof, later became known as Pieternella van die Kaap.

She entered into marriage with a VOC farmer, and together they had four sons and four daughters. Krotoa’s descendants include prominent Afrikaner families like the Peltzers, the Krugers, and the Steenkamps. The artwork also serves as a commentary on how women’s sexuality has historically been objectified, desired, and exploited by men. The depiction of an empty womb could represent Krotoa’s anguish and loss over the separation from her children.

It is worth noting that the acknowledgement of Krotoa’s descendants and their integration into Afrikaner lineages was met with vehement denial by white South Africans in the past. During the era of Apartheid, that was characterised by “white” supremacy, this recognition conflicted with the prevailing ideology.

Krotoa is also seen as the mother of Afrikaans. She was one of the first people to speak both the KhoiKhoi language and Dutch. Today many KhoiKhoi words are officially adopted into Afrikaans.

Lady Skollie aims to draw our attention to the suffering and struggles of her Khoisan ancestors, caught in the midst of two contrasting cultures during a turbulent era of colonisation. Similarly, Lady Skollie herself has experienced the sense of being caught between two cultures. Born in 1987, she witnessed a pivotal period of change as the resistance against Apartheid grew stronger.

In 1991, the doors of white schools opened to children of all races. Lady Skollie, a coloured girl raised in Cape Flats, had the opportunity to attend a prestigious white school. Reflecting on this experience, she remarks,

“We go to white schools and try to assimilate to whiteness, a result of apartheid, but we cannot assimilate too much. Our success has limitations. So my princess Krotoa wears a collar, but it’s broken.”

Lady Skollie

The modern representation of Krotoa shows the breaking of her shackles, signifying newfound freedom.

Both the chains and the moon are depicted using crumpled gold leaf, intricately connecting them. In the Khoisan religion, the moon holds particular significance as a deity embodying the remarkable power of resurrection, undergoing rebirth every 29 days. By visibly intertwining the chain with the moon, it symbolises the Khoisan god breaking Krotoa’s shackles, liberating her and facilitating a rebirth of her spirit. However, she must now navigate her way and shape a new future for herself.

Furthermore, the moon takes on the appearance of a yoni shape, possibly alluding to new deceptive promises that may ultimately lead to fresh forms of confinement. It serves as a cautionary reminder to women to remain vigilant against the power dynamics imposed by men.

Also encrusted with Gold Leaf is a halo around the papaya head. The halo is a symbol of holiness and establishes Krotoa as a martyr and a saint.

2. Khoisan Kween Mother. 2019

In 2019 Lady Skollie painted this mural, especially for an exhibition in London. It envisions a Khoisan queen, arms raised to the sky, smiling, while Khoisan ancestors dance inside her halo. She is wearing a slave collar with no chain attached, rocking a banana skirt and a bright red manicure.

Oh my goodness, so much going on in this artwork. Let’s start by picking apart some of the symbols. So a Banana Skirt? What’s up with that?

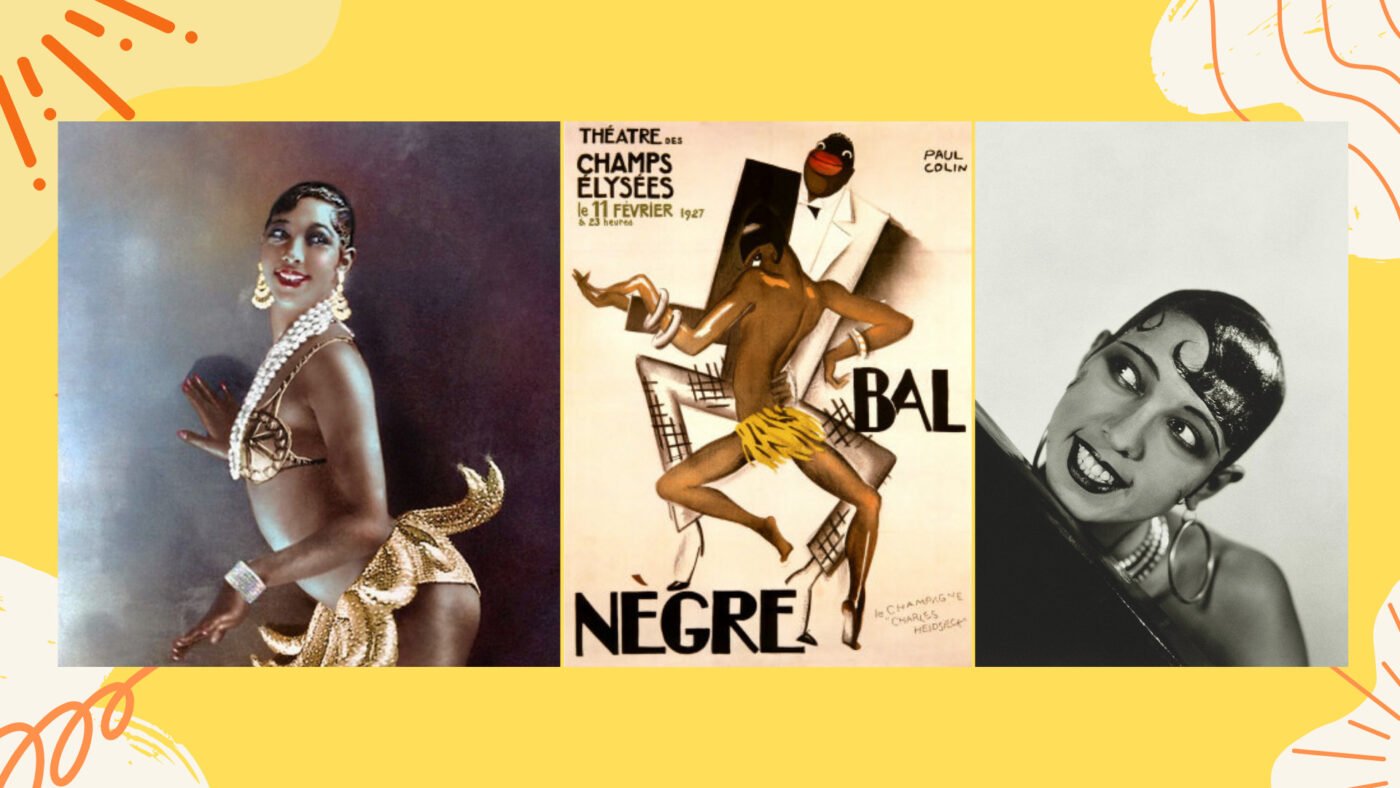

Travel back in time to the summer of 1926 in Paris. Picture this: a bustling theatre filled with eager Parisians awaiting the start of La Revue Nègre, a jazz-infused musical extravaganza. Suddenly, from atop a palm tree, Josephine Baker emerged in her iconic outfit—a skirt made of 16 rubber bananas, accompanied by pearl strings and wrist cuffs. As she began to dance, the atmosphere crackled with electricity and astonishment. Her performance shattered preconceived notions of race and gender, redefining them through style and artistry.

Throughout history, the black female form in Europe has been burdened with damaging stereotypes, portraying black women as sexually deviant, primitive, and hypersexual—a spectacle subjected to the perverse white male gaze. This dance, the danse sauvage, propelled Baker to become the world’s biggest black female star almost overnight.

The impact was immense. Banana skirt-clad dolls flew off the shelves, and Baker’s devoted fans sought to emulate her look by purchasing Bakerskin, a skin-darkening lotion, and Bakerfix, a hair gel. Postcards featuring Baker in her famous banana skirt circulated widely.

By reclaiming her image, Baker defied societal expectations and forged a groundbreaking career for herself—a feat unheard of for women in that era. Even as her banana skirts evolved into fierce spiked versions in later years, the initial design remains revolutionary. Beyoncé paid tribute to Baker by donning a banana skirt during her 2006 Fashion Rocks performance. Rihanna made a memorable statement at the 2014 Fashion Awards, wearing a sheer Baker-inspired dress.

In this vibrant mural, Lady Skollie pays homage to Baker. By depicting her Khoisan Queen wearing the iconic banana skirt, it becomes a powerful commentary on the over-sexualization of the black female body. Links it to Sarah Baartman.

Zoom in on the collar worn by the queen. It symbolises the profound impact of colonialism and the slave trade on the indigenous Khoisan people. Although no longer connected to a chain, the queen still wears the collar, representing how the consequences of this destruction persist today as indigenous communities strive to reclaim and revitalise their cultural identities.

The title “Kween Mother” holds significance, particularly as this art exhibition in London. It alludes to the Queen of England and the monorachy role in colonialism. Lady Skollie explains, “You can’t discuss the UK and South Africa without acknowledging colonisation and the destruction it wrought upon Khoisan traditions.”

The deliberate spelling of “Kween” serves as a reminder of the limited education often associated with various coloured neigbourhoods. It refers to the challenges faced in post-apartheid crime-ridden Cape Flats area.

The fact this is a mural painted on a gallery wall is an Ode to Khoisan Cave Paintings. It is all about claiming the space. This is important because this Khoisan Kween, references both Sarah Baartman and Krotoa as influential historical Khoi women who suffered under colonialism. It’s about rewriting history.

Europeans travelled to South Africa, dispossessing the Khoikhoi of their land, culture, and language in the name of colonialism, serving the interests of their kings, countries, and empires. Almost 400 years later, Lady Skollie, a descendant of the Khoikhoi, ventured to London to showcase her art, shedding light on the influence of colonialism on her culture and community.

“I was on MTV Africa yesterday, and they were like, Lady Skollie – colonising London! It’s not about colonisation. It’s about confronting them and making them notice, ”

said Lady Skollie.

Through the skilful use of repetitive patterns, she infuses rhythm into her art. The queen’s entire body is adorned with intricate patterns, paying homage to the significant role that repetition plays in Khoi culture. In Khoi traditions, the act of repeating the same action is integral to entering a trance state, fostering a profound sense of tranquillity and inner peace.

However, this queen goes beyond tranquillity. With her five long arms outstretched and the graceful figures of her ancestors swirling around her halo, she exudes an unmistakable aura of power and majesty. There is no question about who holds authority in this space—the queen reigns supreme.

3. Papsak Propaganda II. Like the clashing image of the champagne flute tower, pouring into the top, trickling to the bottom. 2018

From Lady Skollie exhibition called Papsak Propaganda.

In the background, a settler ship approaches the cape, accompanied by a vibrant rainbow overhead. In the foreground, a towering settler pours wine onto a Khoisan woman’s face, which trickles down her neck and over her breasts. Beneath her, severed Khoisan heads float in the ocean.

Clutched in her hands are bottles of wine, from which she feeds two of the heads as if bottle-feeding them. The remaining heads are each mindlessly drinking their own bottle of wine. The subtitle draws attention to the chain reaction, likening it to a cascading champagne tower, filling from top to bottom. However, the irony lies in the fact that the heads do not appear celebratory; instead, they appear lifeless and devoid of thought. So, who is truly celebrating?

According to Lady Skollie, this artwork speaks about how the colonists weaponised the Khoisan. It delves into the destructive impact of alcohol on the coloured community.

The mid-17th century marked the initial encounter between the Dutch settlers and the Khoikhoi, the first indigenous people of the region. The settlers were in dire need of the Khoikhoi’s cattle, as they required fresh meat to supply their ships en route to India for spice trading. To compensate the Khoikhoi, the settlers started providing tobacco and wine as payment.

As the Dutch expanded their farms, the Khoisan people faced dispossession, extermination, and enslavement. Interactions between the Dutch, British settlers, Khoisan, and neighbouring Bantu populations led to a unique mixed-race community known as the Cape Coloureds. Enslaved individuals from Malaysia, Indonesia, Madagascar, and India were also brought in by the British, further adding to the diverse ancestry of the Cape Coloured population.

As the Khoisan integrated with the Dutch and became enslaved, they were employed on Western Cape farms, particularly wine farms. This gave rise to the dop system, where farm workers received monetary payment along with a daily allowance of cheap wine. The Afrikaans word “dop” refers to a shot of an alcoholic drink. This practice contributed to the exacerbation of alcoholism among farm workers, resulting in significant social harm within communities, particularly among the Cape Coloured community. It trapped them in a cycle of poverty and dependence.

Although the dop system has largely been eradicated today, the legacy remains, as alcoholism continues to be a prevalent issue. The Western Cape still faces one of the highest incidences of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS) globally, and despite receiving cash wages, many workers still struggle with alcohol misuse. Alcoholism remains a significant challenge within the coloured communities of the Western Cape today.

Lady Skollie has a personal connection to the issue of alcohol abuse as her father served as the head of the Liquor Board of South Africa. She remembers accompanying him to small towns in the Western Cape, where he would educate communities about the dangers of alcohol. He would take two tins and place a bean in each. Giving one alcohol and the other water demonstrates the dangers of drinking during pregnancy. The heavy abuse of alcohol was deeply rooted in the culture, making such awareness efforts crucial.

The title of the artwork, “Papsak Propaganda,” has a significant meaning. “Papsak” refers to a cheap wine sold in litres, commonly consumed by Coloured farm workers. It is made from overripe, spoiled grapes that are no longer suitable for sale. The second word in the title alludes to the propaganda machine of the Apartheid regime. Apartheid ensured political, social, and economic dominance by the white minority. Propaganda was employed to maintain white supremacy, controlling the media and shaping a specific image of the Afrikaner volk.

The celebration of Jan van Riebeeck as a national hero and the singing of songs in his honour was part of the narrative she encountered. There she was standing as a coloured girl, a descendant of the Khoisan, asking to thank him, to be grateful that her people were almost destroyed and are still recovering from the aftereffects of colonialism.

It was clear that Lady Skollie was on the wrong side of this narrative. For a creative writing assignment, all the children in the class were asked to write a letter, imagining they just arrived on a boat sailing into Table Bay. They had to close their eyes and imagine what it would have been like. In Lady Skollies’ imagination, she, a Khoisan would have been standing on the beach, not writing a letter to her family back in Europe.

A class outing to Cape Town Castle, where Khoisan people were imprisoned, became a moment of amusement for the white students, highlighting the trauma endured by her ancestors. Reflecting on her childhood experiences, Lady Skollie recognises the power of propaganda in shaping children’s perceptions.

“When faced with propaganda, you can either resist it or just go with the flow.”

Lady Skollie

The rainbow in the artwork serves as a sarcastic reference to the modern propaganda employed in post-apartheid South Africa. It challenges the notion of a “Rainbow Nation” and concepts of unity such as “Ubuntu” and “Simunye.” The artwork aims to rewrite narratives, reevaluate long-held stories, and confront the true struggles faced by South Africa and the factors that have brought the nation to its current state.

4. Cut-cut, kill-kill, stab-stab: a South African love story. 2016.

Lady Skollie an advocate against Gender-Based Violence (GBV), she fearlessly raises her voice, using her art as a powerful tool for social change.

Gender-based violence (GBV) remains a deeply rooted and extensive issue in South Africa, impacting almost every aspect of life. South Africa has unprecedented levels of woman abuse and violence. The most recent data from the World Health Organisation shows that South Africa’s femicide rate was almost five times higher than the global average. This systemic problem is deeply ingrained within South African institutions, cultures, and traditions.

It’s a political thing to be a woman in South Africa, regardless of race, gender or background.

– Lady Skollie

One particular week in August 2019 left a profound impact on the nation. The tragic death of Uyinene Mrwetyana, a 19-year-old first-year student, shocked and outraged the South African population. Her disappearance for nine agonising days spurred a nationwide search with the hashtag #bringnenehome. Regrettably, the search concluded when her burned body was discovered.

It was revealed that Uyinene had visited the post office to collect a package, where she was brutally raped and killed by one of the staff members. This incident ignited the #TotalShutDown protests held across the country, demanding urgent action against GBV.

Unfortunately, violence against women often faces a lack of serious attention from local authorities in South Africa. While political leaders may acknowledge it as a “national crisis” and pledge resources, the endemic nature of this issue hampers decisive action, and officials may dismiss or trivialise women’s reports of crimes. During the COVID-19 lockdown, many women were trapped with their abusers, leading to an alarming escalation of GBV in South Africa.

With all the protests, Lady Skollie’s art became more relevant than ever and a large part of fighting back and raising awareness of GBV. She has always been passionate about sex education and used to run a blog and radio show focusing on sex education called Kiss and Tell with Lady Skollie.

South Africa is suffering from Rape Culture. South Africa has one of the highest rape statistics in the world, even higher than some countries at war, and statistics confirm this. There were 42 289 rapes reported in 2019/2020, as well as 7 749 sexual assaults. This translates into about 115 rapes a day. But honestly, I don’t even know if any of these statistics are accurate. Many women live in fear of what will happen if they do report a crime; they tend to stay silent.

Lady Skollie’s painting “Cut-cut, kill-kill, stab-stab” deals with the gaslighting of women’s faces when they’re reporting cases of sexual assault to the police.

Lady Skollie has a series of artworks dealing GBV. They tend to be vibrant and colourful, often featuring luscious fruits that initially exude a sense of joy and appeal. However, upon closer inspection, reading the titles and grasping the underlying message, it delivers a profound impact, striking the viewer like a forceful blow to the gut.

Despite their seemingly ordinary nature, fruits possess the remarkable ability to evoke strong emotions. Lady Skollie skillfully employs fruits, such as sliced paw-paw and apples, as potent metaphors for genitalia. This artistic choice aligns with a longstanding tradition among feminist artists who have utilized food imagery to portray the female body as an object subjected to consumption. Furthermore, it cleverly references the Biblical tale of the forbidden fruit, which led to Adam and Eve’s expulsion from the garden. The act of cutting the fruit also conveys a sense of violence, adding another layer of meaning to the artwork.

[…] I think sometimes I don’t only wrap provocative elements in sweetness but also the rot. No one wants to look at rot, but once it has a layer of sweet, we try to ignore that stench of violence

– Lady Skollie

It is time for people to feel uncomfortable and for people to ask themselves very hard questions about how they relate to women, how they treat them, how they talk to them

– Lady Skollie.

Lady Skollie fearlessly harnesses her art to dismantle patriarchal power structures and expose societal inconsistencies. Through her thought-provoking works, she challenges gender roles and encourages viewers to reconsider their beliefs. Combining influences from the ancient Khoisan heritage with contemporary political relevance, her works convey potent messages about consent and power dynamics.

5. The artist’s booty print, objectified by eyes and digital media, 2016

In this artwork, we encounter ink prints of Lady Skollie’s bum on canvas, a process that must have been super fun to make. Surrounding her buttocks are numerous eyes, some judging, while others admire. Many hands are engaged in taking selfies, capturing the moment.

Lady Skollie often utilises humour as a means to convey her thought-provoking messages.

“I use humour as a way of unwrapping severe issues in a palatable way — so that people will actually start thinking about change,”

– Lady Skollie.

This particular work delves into her identity as a Khoisan-coloured woman in the contemporary world, drawing a parallel to the narrative of Sarah Baartman.

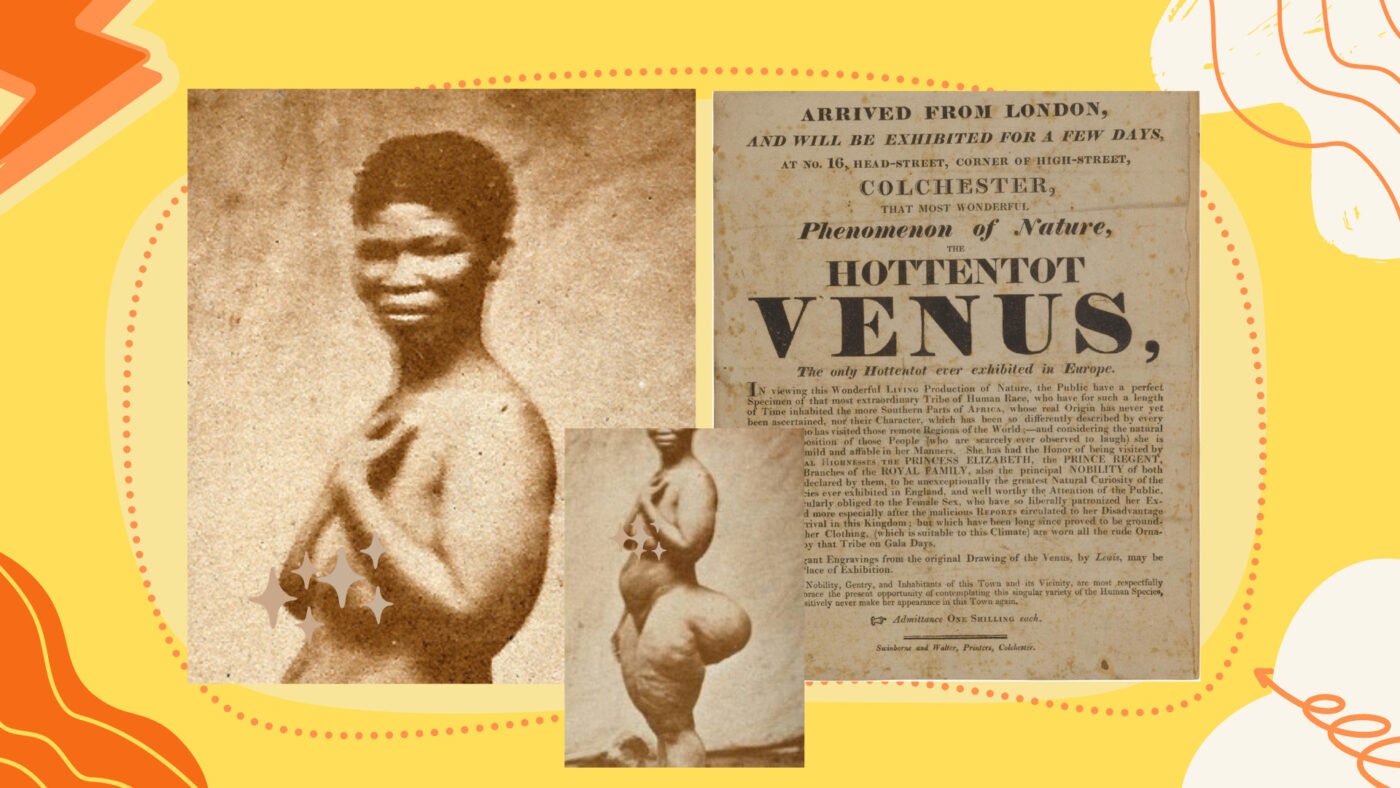

Sarah Baartman (1789 – 1815), also known as Saartjie Baartman, was a Khoikhoi woman who was exploited as a freak show attraction in 19th-century Europe under the deplorable name of the “Hottentot Venus.” The Khoisan were called the ‘Hottentots’ by European settlers. Hot-Tot was supposed to mimic the click sounds and staccato pronunciations that characterise the Khoikhoi language, which was so different from any European language. These terms are deemed derogatory today because of their connotations of slavery and Apartheid. European audiences flocked to see Sarah Baartman due to her steatopygic body, which was considered unusual in Western Europe.

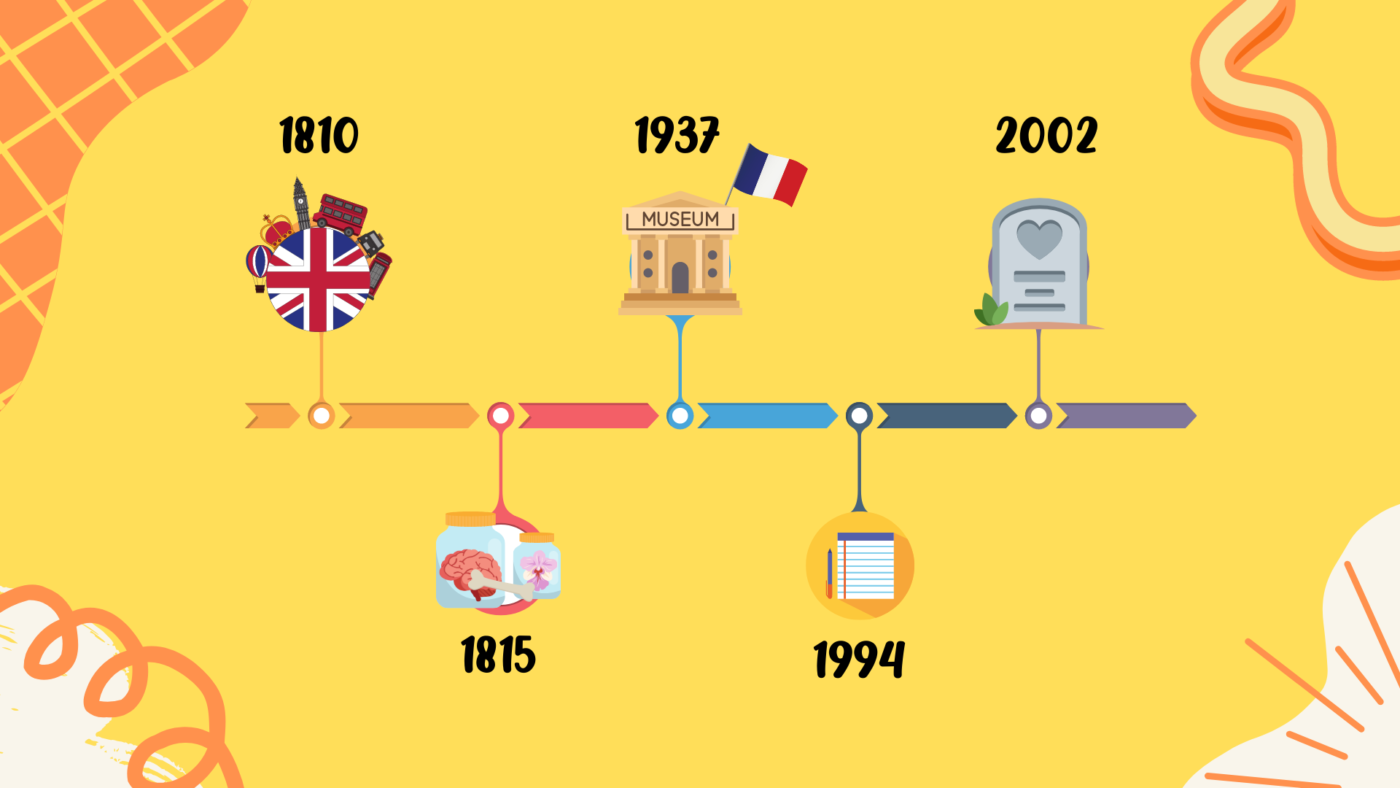

Now I am sure many of you know of Saartjie, but do you know the extent of her story? The details are shockingly disturbing. She was promoted as the “missing link between man and beast”, which sparked a disturbing fascination with her genitalia among the European public. Scientists dissected her body, and a museum retained her remains, including her brain, genitalia, and skeleton. The timeline of Saartjie’s restitution is deeply troubling. She departed for Britain in 1810, passed away in 1815, and her remains were put on display.

In 1937, they were transferred to a new museum. Finally, in 1994, Nelson Mandela officially requested her remains to be returned to South Africa. Following extensive debates, her remains were repatriated in 2002, and she was laid to rest in peace. That’s an awfully long time before she received a proper burial if you ask me. Sarah Baartman has become an icon in South Africa, symbolising various aspects of the nation’s history. Her story epitomises the racist colonial exploitation that occurred, highlighting the commodification and dehumanisation of black individuals.

European colonisers exerted control and authority over the Khoikhoi people, simultaneously constructing racist and sexist ideologies about their culture. London, in particular, was where Sarah Baartman was exhibited as a “wild, savage, unclothed, and untamable woman.” Her body became a symbolic representation of “all African women,” playing a pivotal role in colonising parts of Africa and shaping narratives.

Travel accounts and imagery depicted Black women as “sexually primitive” and “savage,” perpetuating the belief that Africa would benefit from colonisation by European settlers. Colonisers believed they were reforming and correcting Khoisan culture in the name of Christianity. Dehumanising the Khoisan was deemed necessary to strip them of their human rights and establish dominance and supremacy.

Lady Skollie’s representations of Sarah Baartman differ from historical representations and are also seen as a self-portrait.

‘My family used to call me ‘Saartjie’, the diminutive form of Sarah, as a joke. [because of my big bum] I remember being consumed by a vague feeling of shame”

– Lady Skollie.

Through portraying herself as Sarah Baartman, Lady Skollie directs our attention towards the unrealistic ideals imposed on the female body, particularly the black female body. Historical evidence suggests that Sarah Baartman’s features were exaggerated in illustrations to further emphasise her “freakish” nature and enhance her appeal as an attraction. Even her facial expression was depicted to imply a lack of intelligence. However, it is important to recognise that Sarah Baartman was far from unintelligent. In reality, she was a multilingual individual who spoke three languages fluently. During her trial, she eloquently defended herself in Dutch and was even skilled in playing the harp.

The legacy of Baartman has been resurrected recently with renewed attention to issues of body shaming and objectifying women of colour. Rumours circulated that Beyoncé wanted to make a movie with herself starring Sarah Baartman. Reality TV star Kim Kardashian also referenced Sarah Baartman in her widely publicised “Break the Internet” nude photo shoot for Paper magazine in the fall of 2014. Besides showing off her rear end, Kardashian is also seen recreating an iconic 1976 photo of model Carolina Beaumont by photographer Jean-Paul Goude which was embedded with Sarah Baartman references. Critics felt that it showed a lack of respect for the indignities Baartman endured. Sarah Baartman’s story is about centuries of trauma under Colonialism.

Various South African fine artists have created artworks to honour Sarah Baartman, to clothe her with dignity and give her an honourary place in South Africa’s troubled history. These include Willie Bester’s iron sculpture, Penny Siopis’s exhibition called “I am Saartjie” and international French artist Brigitte Derbigny.

This show is dedicated to Sara Baartman and the years she was stripped, put in jars, preserved and paraded against her will. Now my ass has become my Samson’s mane; I draw strength from it. I revel in it. I take pictures and videos of it that I’ll never share because what if I contribute to the over-sexualization of the black female form? What if I’m just a 2016 version of Sarah rolling in my digital grave trying to find the perfect ass pic angle.

– Lady Skollie

Lady Skollie’s art also underscores the unfortunate truth that unrealistic expectations of the female form have not changed much over the years.

Conclusion

And that concludes the five artworks you need to know by the daring artist Lady Skollie.

Lady Skollie is an exciting and unapologetic artist who challenges societal norms. She aims to spark conversations about rape culture in South Africa through her politically-charged paintings that reflect women’s realities. Her art uniquely blends elements of fruit, humour, violence against women, and her Khoisan heritage, addressing the impact of colonialism and apartheid on her culture.

Lady Skollie has not only achieved recognition as an artist but has also become a fashion icon, merging urban-coloured street style with Khoisan influences. Her talent and creativity have led to collaborations with fashion brands like Woolworths. Notably, she was commissioned to design a commemorative coin for South Africa’s 25th anniversary of democracy, portraying stylised Khoisan figures participating in their first vote. Lady Skollie’s art has gained critical acclaim both locally and internationally, earning her awards such as the FNB Art Prize.

Her work has been showcased in renowned galleries, museums, and art fairs worldwide, including the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa, the National Gallery of Zimbabwe, the London Art Fair, and Art Miami. Lady Skollie’s bold, honest, and unapologetic exploration of complex themes resonates with audiences and contributes to her growing recognition as an exceptional artist.

I’m that dirty auntie Skollie who says all the shit you’ve been thinking but never admitted to. It’s coaxing things out of you with a bright and sunny disposition. Humour is a perceptive vehicle for social change. People hate being preached to, but they’ll listen if you wrap it up in sexy.

– Lady Skollie

BUY OUR LADY SKOLLIE WORKSHEETS

Worksheet pack that includes notes and fun activities. Ideal for art students and history students to learn more about the South African Artist Lady Skollie

Resources

Abrahams, Yvette. Was Eva raped? An exercise in speculative history. Kronos No. 23 (November 1996) , pp. 3-21 (19 pages) Published By: University of Western Cape

Camissa Museum (2021) Krotoa – Khoi Child, YouTube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tbEm7b7N5iM (Accessed: 22 June 2023).

Deevia Bhana Professor Gender and Childhood Sexuality (2023) Rape culture in South African schools: Where it comes from and how to change it, The Conversation. Available at: https://theconversation.com/rape-culture-in-south-african-schools-where-it-comes-from-and-how-to-change-it-166925 (Accessed: 28 June 2023).

Gouws, A. (2022) Rape is endemic in South Africa. why the ANC government keeps missing the mark, The Mail & Guardian. Available at: https://mg.co.za/thoughtleader/opinion/2022-08-09-rape-is-endemic-in-south-africa-why-the-anc-government-keeps-missing-the-mark/ (Accessed: 28 June 2023).

Hlalethwa, Z. (2019) Lady Skollie: A pussy power prophet delivers us from good and evil, The Mail & Guardian. Available at: https://mg.co.za/article/2019-06-17-00-pussy-power-prophet-delivers-us-from-good-and-evil/ (Accessed: 28 June 2023).

Hart, G. (no date) Drowning and denialism: Lady skollie’s ‘good & evil’, ArtThrob. Available at: https://artthrob.co.za/2019/06/21/drowning-and-denialism-lady-skollies-good-evil/ (Accessed: 20 June 2023).

Mellet, T. (2016) Krotoa – drawing the longbow in the fort 1642 – 1674, Camissa People. Available at: https://camissapeople.wordpress.com/2016/08/20/krotoa-drawing-the-longbow-in-the-fort-1642-1674/ (Accessed: 15 June 2023).

NB-Uitgewers/Publishers (2020) Patric Tariq Mellet’s ‘The lie of 1652’ is a plea for restoration and recognition of the ties that bind us as Africans, TimesLIVE. Available at: https://www.timeslive.co.za/sunday-times/books/non-fiction/2020-09-29-patric-tariq-mellets-the-lie-of-1652-is-a-plea-for-restoration-and-recognition-of-the-ties-that-bind-us-as-africans (Accessed: 03 July 2023).

Sexual violence in South Africa (2023) Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sexual_violence_in_South_Africa (Accessed: 03 July 2023).

http://www.e-family.co.za/ffy/RemarkableWriting/UL021Krotoa.pdf

http://www.e-family.co.za/ffy/g8/p8000.htm