Art History

7 Characteristics in weaver Allina Ndebele’s tapestries, who trained at The Rorke’s Drift Art and Craft Centre.

7 Characteristics in weaver Allina Ndebele’s tapestries, who trained at The Rorke’s Drift Art and Craft Centre.

Hey there, art enthusiasts! I’m artist Lillian Gray, and today I’ve got something exciting to share with you. Get ready to meet an incredible South African artist named Allina Ndebele.

Allina Ndebele is a super-talented weaver who creates tapestries that capture the traditions and stories of the Zulu tribe. It’s truly remarkable how she managed to become a respected artist, despite facing many challenges. She grew up in a traditional rural setting, where unfair rules from the time of Colonialism and Apartheid held her back. Plus, she had to deal with poverty. But guess what? Allina didn’t let any of that stop her!

Today, she is celebrated and honoured for her unique style and storytelling in her tapestries. She’s one of the most famous female artists from The Rorke’s Drift Art and Craft Centre in Kwa-Zulu Natal, South Africa. If you want to learn more about the centre, check out my video!

Oh, and by the way, I’ve got some awesome worksheets related to Rorke’s Drift available in my TpT Store. They’re designed for different ages and are loads of fun, so make sure to check them out!

In this video, I’ll take you through Allina’s biography, discuss her weaving process, and talk about seven characteristics of her tapestries. And to top it off, I’ll dive deep into two of her most famous works: “The Tree of Life” and “Nqamatshe and his muti magics.”

But before we get into all of that, let’s explore Allina’s inspiring story. Get ready for an artistic adventure!

Biography – Against all odds

Allina Ndebele was born in 1939 in South Africa into a traditional Zulu family. It is always important to note the date an artist lived. It gives us lots of clues about the time period, the zeitgeist the artist grew up in. To fully appreciate Allina’s story and artworks you need to know that South Africa went through Colonialism, which led to segregation, which transformed into Apartheid.

When the British arrived in Zululand, they imposed their own laws, governance systems, and cultural practices on the indigenous Zulu people. The British authorities frequently took away Zulu land, causing the displacement of the people and the disruption of their traditional way of life.

The arrival of European Christian missionaries, including Lutheran missionaries, also brought significant changes to the religious practices of the Zulu people. The missionaries aimed to convert the Zulu population to Christianity and introduced new religious beliefs and practices. The Zulu people were encouraged to abandon their ancestral worship and adopt Christianity as their primary religion.

So little Allina was born as a Zulu girl in a Lutheran Mission Station at a time when there was a lot of tension between traditional beliefs and the church. She was raised with her gogo, her grandmother always telling her stories of the Zulu tribe long before Colonialism. Allina fondly remembers listening to her gogo late at night huddled around the fire with the other kids from her village, listening to all of Gogo’s outrageous stories. These old stories were untainted by Christianity. Being curious she would often pester gogo to tell her favourite stories over and over.

However, these stories were not encouraged by the church and were seen as a threat to Christianity.

It created a lot of tension within Zulu families and communities as individuals navigated the complexities of merging their traditional beliefs with the new Christian teachings.

Allina also had to face the hardship of poverty and discrimination. To keep the economy running, the Apartheid government needed a cheap source of labour. So, they created a system of black migrant workers who had to leave their families and homes in the homelands and travel to work in the cities or mines owned by white people. Allina and her siblings were raised mainly by her mother since her father had to go work in Johannesburg.

She was also held back by discriminatory Apartheid Education policies. The government wanted to limit the education of black students so that they would be prepared only for jobs that were considered lower in status. Despite all this, Allina completed her Junior School Certificate (St9 / Gr7). Her tertiary education was limited by the Extension of University Education Act of 1959. Like so many other black women she then applied to study nursing.

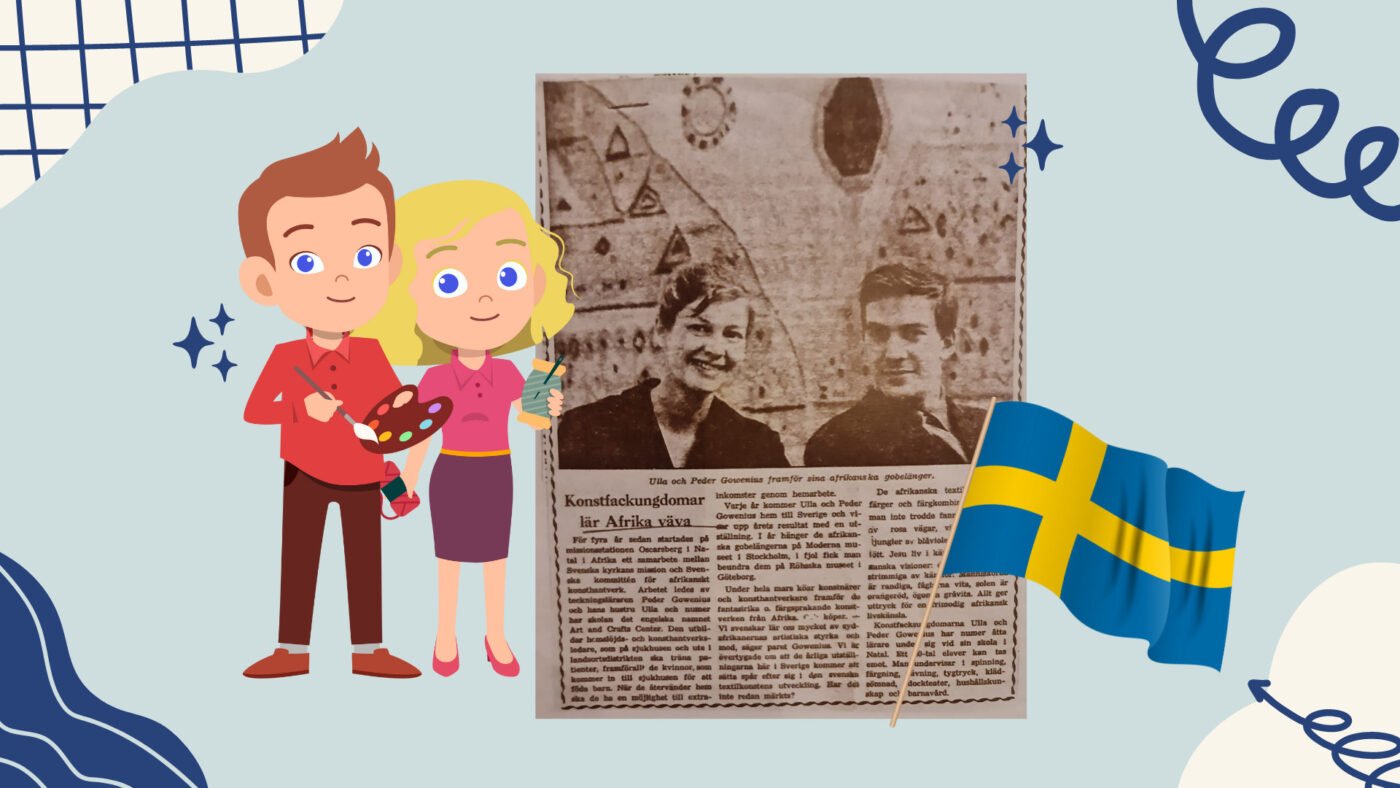

While working at Ceza Mission Hospital, she met a Swedish couple named Peder and Ulla Gowenius, who were teaching craft skills to black patients in the hospital. They asked Allina to be their translator for a weaving workshop, where she discovered her talent and love for weaving.

Peder and Ulla decided to establish an official arts and crafts centre and start teaching skills to all aspiring artists – no matter their skin colour.

Allina decided to join the couple at The Rorke’s Drift Art and Craft Centre. Peder encouraged students to find their own voice and tell their own stories. Allina recalls an interaction between them where Peder said, “Why not weave your own wedding?” And Allina said, “I had a Christian wedding”, which made her feel uninspired and bored. Peder replied, “Why not imagine the wedding you wanted to have?” Immediately Alina’s imagination ran wild with a wedding set in a jungle, with African animals and vibrant Colours.

Throughout her career Allina was naturally more drawn to traditional Zulu stories than Bible stories. She always felt more free and creative when working with tribal stories as opposed to Biblical tales.

Allina was a remarkably talented student. After intensive training by Ulla, she was awarded a scholarship to train further in Sweden. She returned later to become a full-time teacher at Rorke’s Drift.

To beginners, Allina taught basic weaving techniques, preparing one’s wool, dying wool, and achieving the correct tension in the thread. Geometric rugs were often made at Rorke’s Drift, however, what Allina was really drawn to was when students mastered the basics of weaving and could proceed to depict and tell stories.

After 15 years at Rorkes Drift, she was tired and exhausted. She felt that she was constantly teaching and had little time to develop her own art. She left Rorke’s Drift and moved back to her father’s land. There she started her own studio, which she named “Khumalo’s Kraal Weaving Workshop.” She needed to build up a body of work if she wanted to become a recognised artist in her field.

Summoning the ancestors – Building a traditional home.

At first, Allina felt a bit lost being on her own and having to produce tapestries. She wanted to tell stories of a time long before colonialism that was passed down by her Zulu ancestors. But she struggled to connect and speak to the ancestors.

To help her imagine and develop these stories as images, she felt the need to build a traditional Zulu home called an amaqugwana. However, building traditional houses like this was discouraged on Christian missions like the one she lived on.

At first, the mission officials resisted Ndebele’s desire to build a traditional dwelling because they didn’t understand her need for inspiration. Eventually, they did allow her to build a traditional home. She often translated and wrote documents for the mission and they wanted her to remain happy.

Allina Ndebele believed that her artistic inspiration came from engaging with the spiritual domain of her ancestors. It is believed that one’s ancestors’ spirit dwells inside the amaqugwana. She followed traditional procedures, made offerings and slept on a goat skin. Ndebele finally felt a strong connection to her grandmother’s spirit in this place. Through dreams, Ndebele received stories from her grandmother and incorporated them into her tapestries. By building the traditional Zulu home and following these traditional practices, Ndebele honoured and acknowledged her ancestors, believing that neglecting them could bring misfortune.

Her works seemed to thrive without the strenuous demand of teaching all day and living in her own traditional home. Most of her oeuvre was created during this time, until her retirement in 2005.

Overcoming poverty.

However, the work was not without its challenges. In the past, older women were often admired for their storytelling abilities. They were considered precious keepers of stories and wisdom. However, they didn’t have much power in society beyond this role. They didn’t have control over important decisions, and it was difficult to build wealth, since they weren’t allowed to own land.

With the encouragement of Jules and Ada van der Vijver, art teachers at Rorke’s Drift at the time, she embarked on the next phase of her life. Dyeing her wool required her to walk two kilometres to the river close to her house. Often the weaving of the tapestries had to be done by the light of candles or paraffin lamps because there was no electricity. She relied on buying off-cut wool from and strands the Rorke’s Drift Arts and Craft Centre. Only later, in the year 2000, she had access to running water at her house.

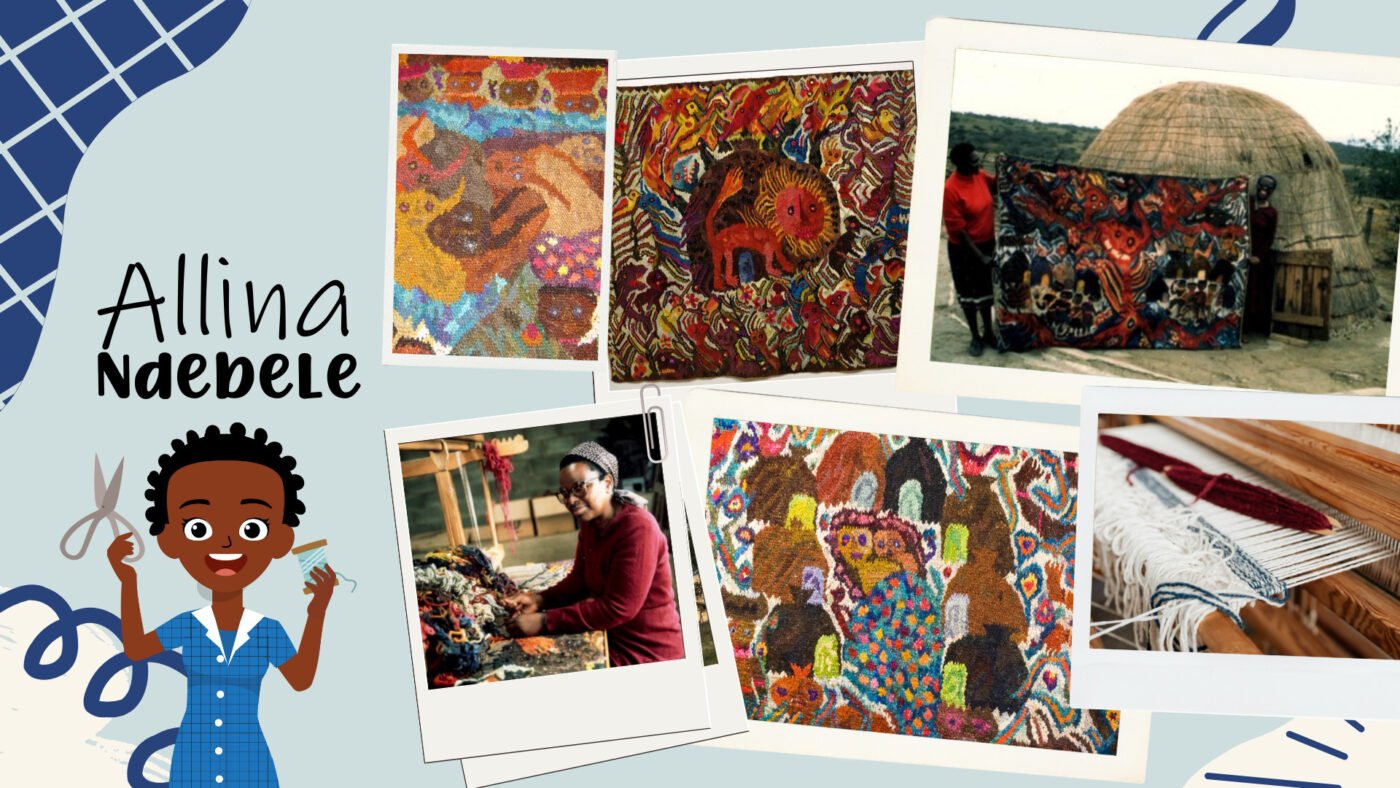

Weaving is a time-consuming craft, some tapestries took over a year to complete, however over her career, Allina produced over 100 unique narrative tapestries.

Recognitions, Exhibitions and Awards

Her artistic talent gained recognition, and she exhibited her work in various galleries and museums, both locally and internationally. In 2005, she received the Order of Ikhamanga in Silver, a prestigious award for her contributions to the creative arts.

Allina Ndebele’s work is held in permanent collections of almost every major South African art museum, as well as internationally, among others in the USA, Sweden, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland and Australia.

Allina’s Weaving Process – “Free weaving” – no planning or sketches.

Allina Ndebele, a celebrated artist today, is known for her unique “free weaving” style. This technique, taught to her by Ulla Gowenius, allowed her to create spontaneous designs without a preconceived plan. Allinas’ work has been described in the past as painting with wool. Instead of making detailed sketches beforehand, Allina would visualise the image in her mind and start weaving, making choices as she went along.

Free weaving presented its challenges, especially when weaving curved shapes and interlocking them. However, Allina embraced the difficulty and trusted her instincts throughout the process. She didn’t fear the uncertainty of not knowing how the final piece would turn out. This improvisational approach brought an element of surprise and spontaneity to her artwork.

While Allina usually didn’t plan her pieces or make sketches.

When weaving a tapestry the size is restricted by the size of the loom. It is easier to view a work in portrait orientation since it allows the artist to see the artwork the right way up. Allina however wanted to work much bigger and have enough space to tell her stories. She opted for a landscape orientation. This enabled her to make the tapestry as long as she liked. It is harder to do since you do not see your design from the right angle. Due to the size, she also had to roll the design as she worked and could only see a slither of the design as she wove.

Allina’s fondness for creating large tapestries, some measuring up to 4 metres in length, shows us what a skilled weaver she is. She not only mastered the craftsmanship of weaving but could also envision a complete image while only seeing one slither at a time.

Let’s take a closer look at seven characteristics of Allina Ndebele’s unique art style.

7 Characteristics of Allina Ndebele’s work:

1. Traditional Storytelling

The Zulu people have a strong tradition of passing down knowledge and stories through oral storytelling. This serves as a way of preserving their history and culture. The stories, often shared by female elders, teach valuable lessons and moral values. They promote love, discourage hate and warn against negative emotions like jealousy. Storytelling also strengthens community bonds and creates a shared identity. Importantly, storytelling encourages active participation, fostering critical thinking, creativity, and imagination among listeners.

Over the years, colonialism, migrant labour, the Apartheid Homeland scheme and rapid urbanisation all contributed to the decline in traditional Zulu storytelling. Despite these challenges, Allina believes in the importance of teaching and sharing these stories, especially with the English-speaking audiences. She sees herself as a teacher, using her artworks to communicate important lessons embedded within them.

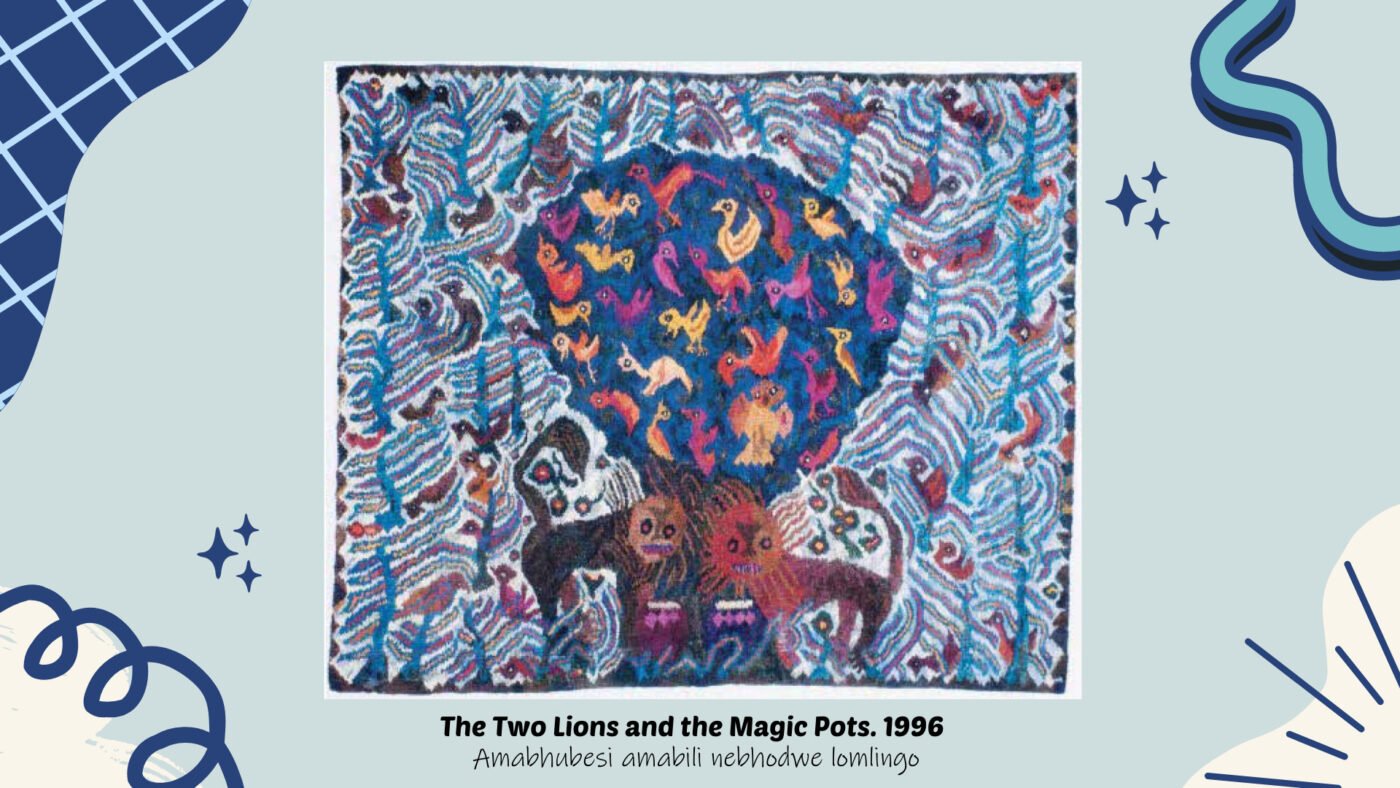

For example the tapestry called “The Two Lions and the Magic Pots,” depict two hungry lions who had scared away all their food, by being extremely rude and loud. They were all alone and feeling very sad. They were extremely hungry! Suddenly, two magical pots appeared and gave them an important message: “If you want to avoid getting in trouble with the birds above, you must stop being mean to others.” The lions promised to be kind, but it wasn’t easy for them. The magical pots kept a close eye on them from a tree nearby to see if they were really changing their ways.

Zulu mythology is complex using various Zulu symbols, important mythical creatures and sangomas also known as traditional healers. Therefor Allina Ndebele often added descriptions to her tapestries.It tells the story and explains specific elements, giving viewers a deeper understanding of the meanings and lessons. However, over time, as her works were sold to private collectors and various galleries, some of these texts became lost. This separation of tapestries from their accompanying texts disrupted the complete understanding of her artworks.

2. The ordered Homestead

In traditional African beliefs, there are two different places: the homestead and the bush. The homestead is where people live and work, and it’s essential to keep things organised and respectful there for their ancestors command it. On the other hand, the bush is a wild and untamed. It can be dangerous, but it’s also filled with special energy and power that Zulu people need in their lives.

The ordered Zulu homestead consists of huts arranged in a specific pattern, has a water source near by and contains a kraal with cattle. The homestead fosters unity, close social bonds, and a collective mindset among extended family members. It also connects the Zulu people to their ancestral roots and ensures the preservation of cultural practices.

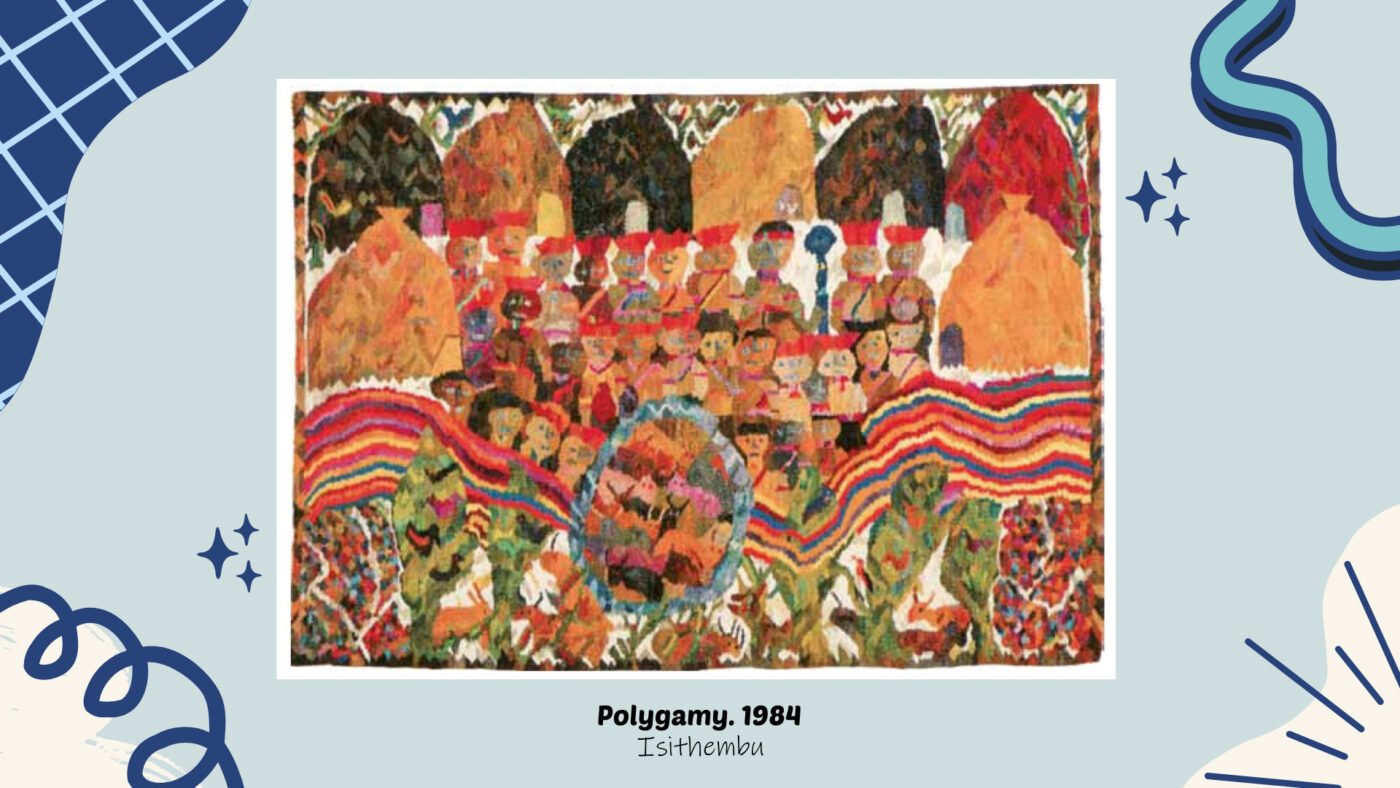

Allina Ndebele often depicts the ordered Zulu homestead in her tapestries. The tapestry called “Isithembu / Polygamy (1984).” tells a story about Ngolende, a wealthy and powerful man who has many wives, children, and cattle. Having many wives and cattle meant you were rich, and people were jealous of Ngolende. His neighbours planned to kill him and take his wives, but he had a dream warning him of the danger. Ngolende and his sons were able to stop the evildoers and protect their homestead.

In the tapestry, you can see a semicircle of colourful designs around Ngolende, his wives, and his children. In the centre, there’s an oval shape representing the cattle kraal. Beyond the colourful designs, there’s a portrayal of the uncivilised bush, where strange creatures live.

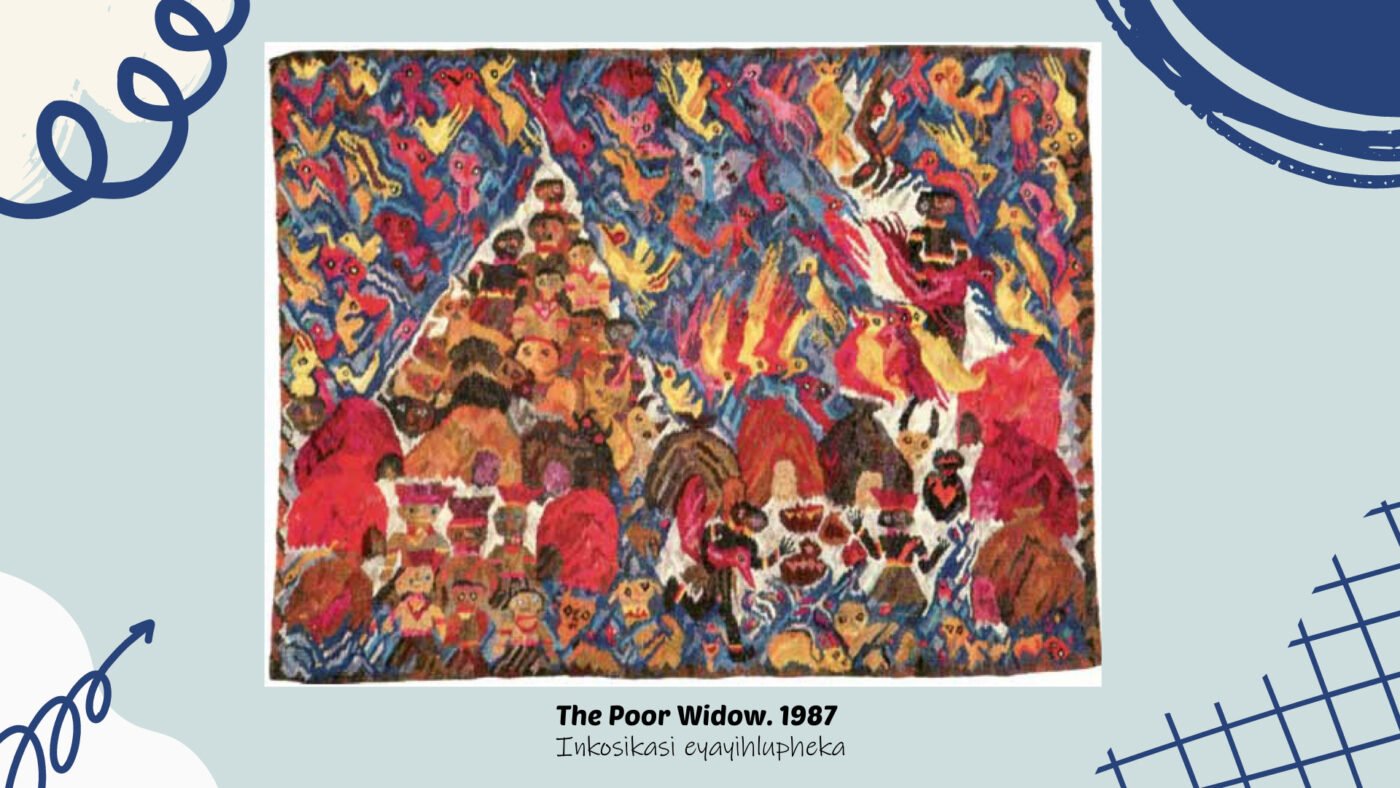

Another tapestry called “Inkosikasi Eyayihlupheka / The poor widow (1987)” tells a different story. The widow has no husband and only one son. They have no fields or cattle of their own, so they have to work for others. The tapestry shows a scattered and chaotic depiction of people, designs, and birds, representing the collapse of social and cosmological order.

It lacks an ordered homestead and stability. The colours used in this tapestry, like red, blue, and yellow, add to the feeling of disorder. However, the story turns out well for the widow and her son. With the guidance of his father’s spirit, the son captures a special bird that provides unlimited supplies of skimmed milk. This brings happiness and ends their hunger.

Both these tapestries show the contrast between ordered prosperity and chaos. They reflect the importance of the homestead’s structure, cattle, and the stability they bring to the Zulu people’s lives.

3. Water

In the Zulu Culture, water holds spiritual and symbolic significance. It is seen as a sacred element that connects their ancestors to the natural world. It is the dwelling place of ancestors, spirits, and other beings. Allina’s tapestries often depicts water bodies swarming with spiritual creatures.

Traditional Zulus believe that water is sent by a powerful being called uMvelingqangi, the Lord-of-the-Sky. He lets living water fall from the sky as rain. These living waters then fills rivers and pools, and eventually becomes the sea. uMvelingqangi also formed the first people in the water from the reeds. It is where people are born and where they return when they die. Water has the ability to judge human actions and also cleanse them.

Traditional healers, known as sangomas, obtain their instruments and powers from under a water source. These tools are protected by a serpent, which keeps away those who are not deserving or qualified to receive them.

Allina often depicts various water sources in her tapestries. Water is spontaneous and unpredictable and is often captured in curves running through Allina Ndebele’s designs. The tapestry “Nqakamatshe and his muti magics” contrasts the fluidity of water with the steadiness of the Zulu Homestead.

Nomkhubulwane is known as the heavenly virgin princess, the daughter of the Lord-of-the-Sky. She is associated with young women and fertility. Men should not look at her, she only reveals herself to children and maidens.

She appears in the morning mists and is linked to the rainbow, sometimes even being considered the rainbow itself. It’s believed that she can bring rain by asking her father, the Lord-of-the-Sky. If she withholds her generosity, it can be very harmful. The absence of water is also often depicted in Allina’s work.

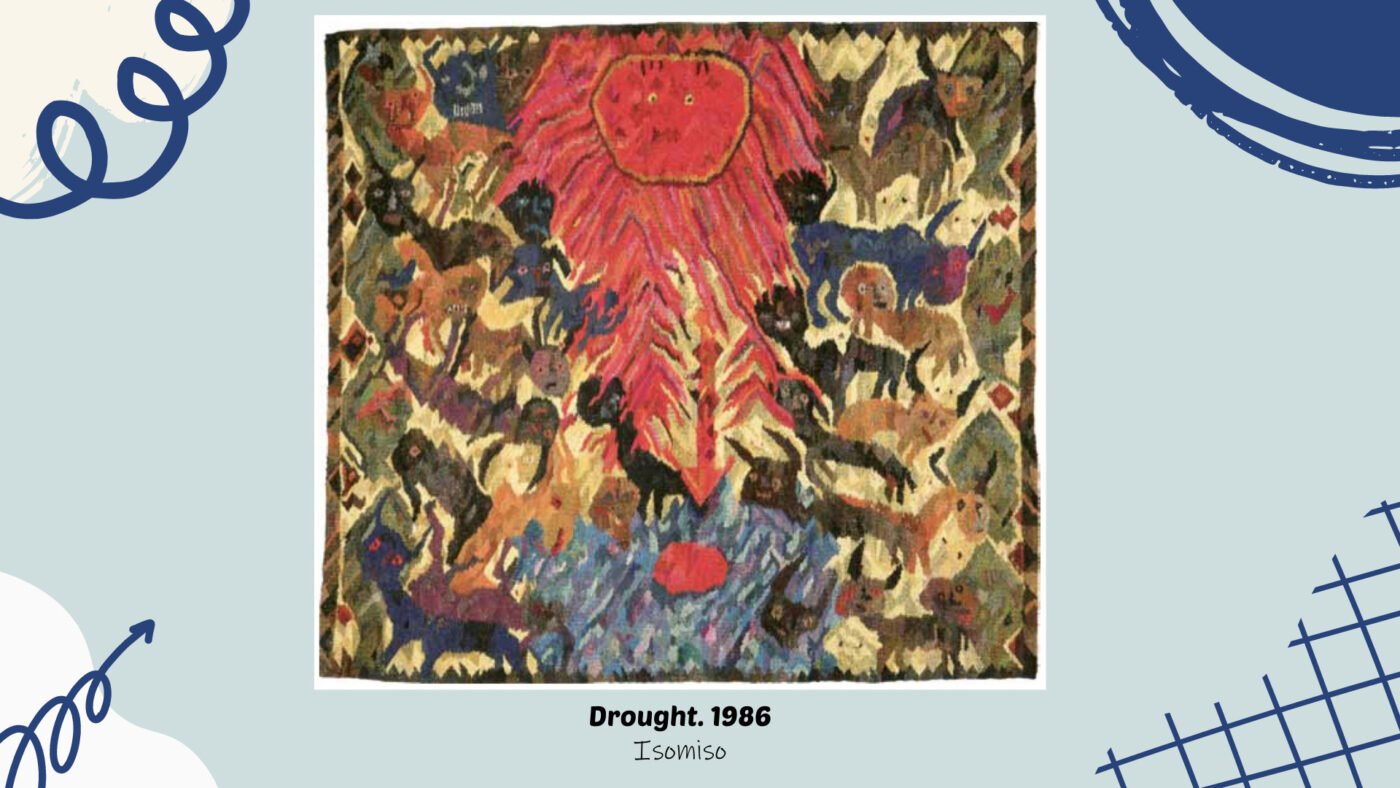

The tapestry called Isomiso / Drought (1986) shows a scorching sun shining directly down from the sky onto the creatures below. In this artwork, the artist portrays the powerful energy of the goddess as fiery bolts of heat. It resembles spears, destroying everything in its path.

The artist explains that during this devastating drought, the sun’s rays were so intense that they felt like spears piercing the water, making it boil. The grass dried up, and the animals suffered. The water in the dams became too hot to drink, and people were too sick and weak to pray for help from Nomkhubulwane.

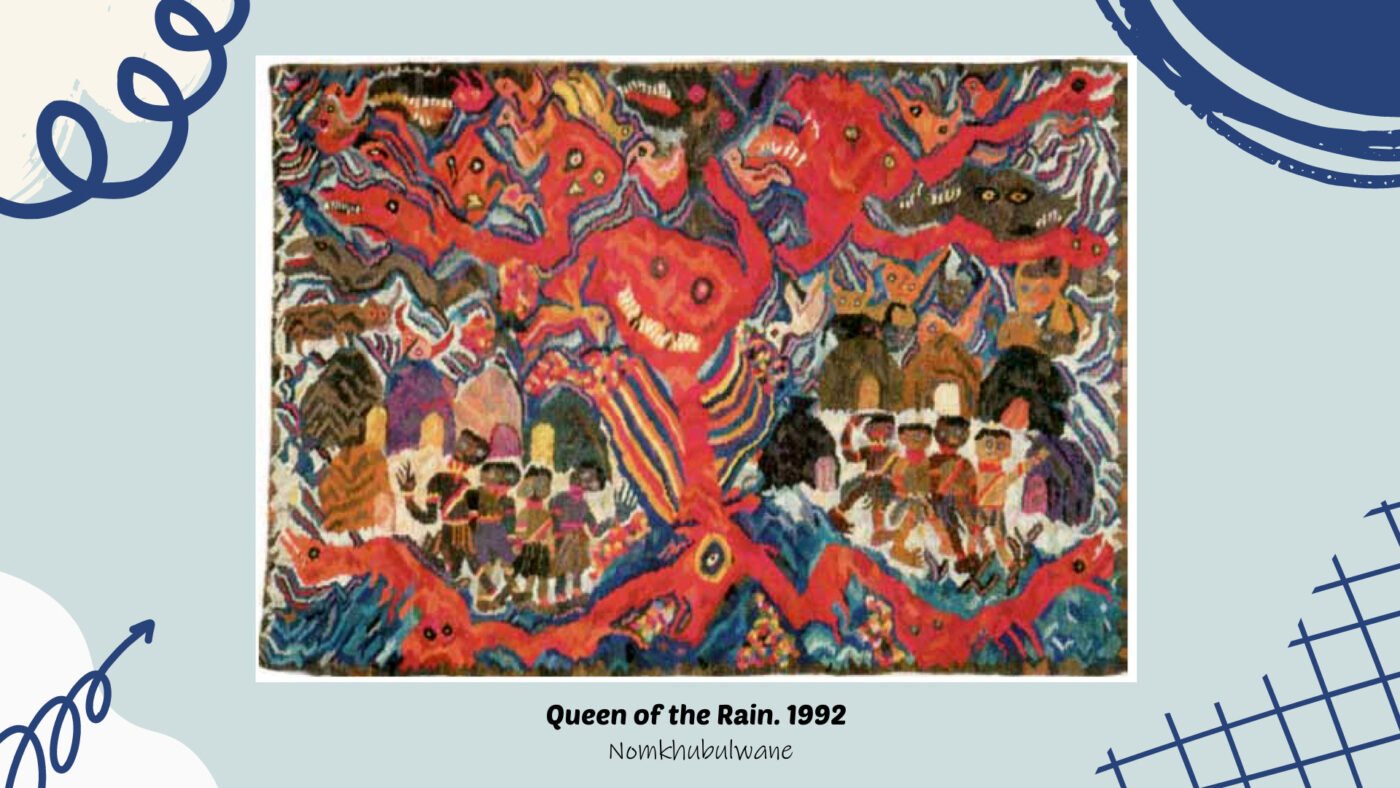

The tapestry, known as Queen of the rain / Nomkhubulwane .1992, depicts a serious drought that Allina’s gogo told her about. Because of the severe drought, the men in a village held a meeting. They decided to honour their ancestors and a deity named Nomkhubulwane.

Each man brought a black ox, and they climbed a mountain. On the summit, they made fires, prayed, and sacrificed the oxen. They feasted, danced, and thanked Nomkhubulwane. When they left, heavy rains fell, and a rainbow appeared. The women found seeds at its end, which they planted. Soon, the village had plenty of food. The artwork depicts powerful natural forces, with a central red face of Nomkhubulwane, showing her teeth. A red bolt of energy strikes from the powerful goddess releasing a rainbow at its sides.

Traditional Zulus believe that the water from the sea is different from the water in a river, and the ancestors love the sea. In Zulu belief the sea is similar to a good person that can’t do anything bad. This leads me to the next characteristic, shells.

4. Shells

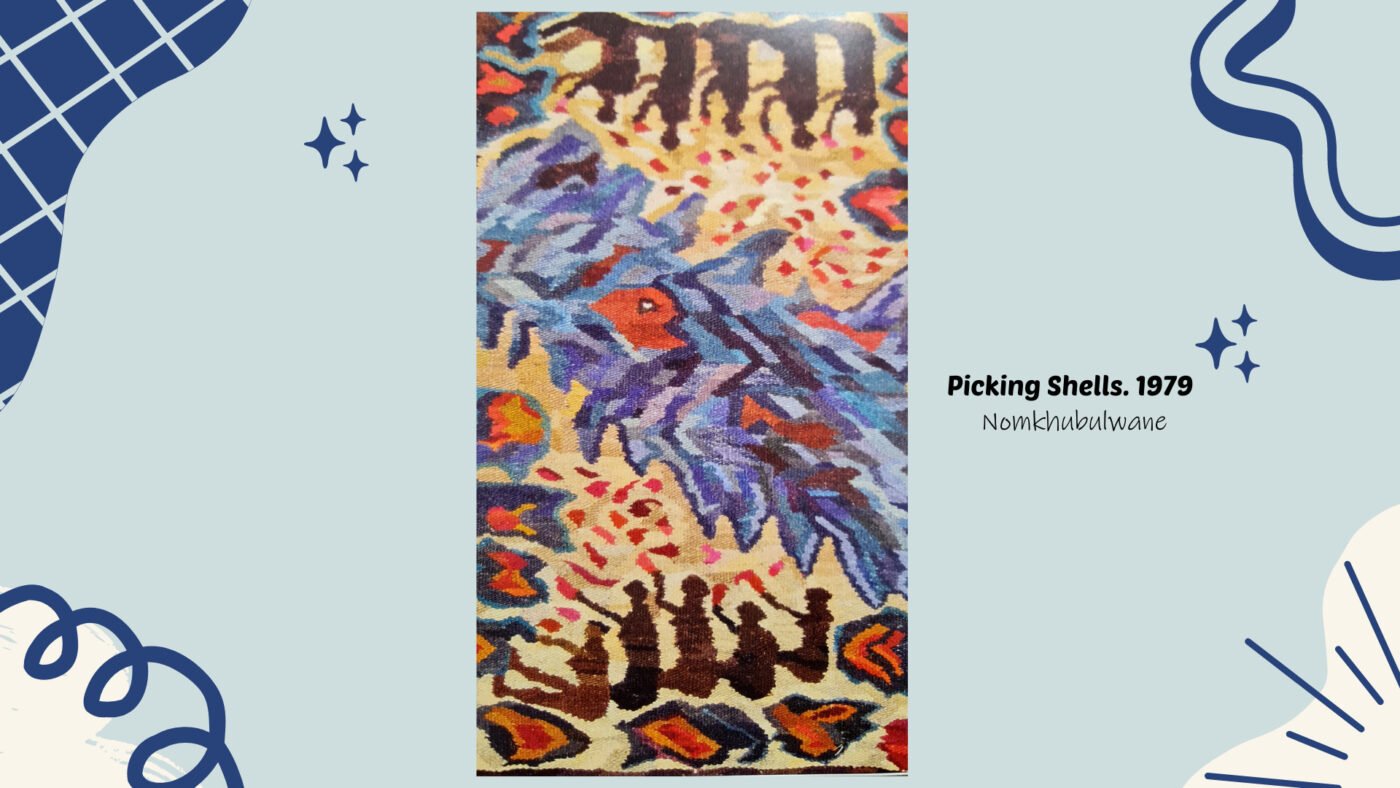

The tapestry “Picking Shells. 1979”, one of Allina Ndebele’s early artworks, focuses on the Zulu’s most sacred body of water, the ocean. The story conveys the importance of shells in the Zulu Culture. They are believed to have unique powers since they come from the underwater world. They are associated with fertility, healing, and protection.

The ancestors are believed to love the sea, and the shells are seen as messages from them, similar to a dream. Shells are symbols of wealth, status, and beauty in Zulu culture. They are often associated with royalty and are used to decorate traditional clothing, jewellery, and ceremonial items. Wearing shells can indicate a person’s social standing. Zulu women often wear necklaces from cowrie shells for protection. They believe that these shells connect them to their ancestors.

The story behind the artwork is about a chief named Nonkanda, who is warned by his ancestors that his daughter, Nomalanga, is in danger. The chief is told to have the girls from the village collect shells from the sea to protect Nomalanga. The artwork shows the girls successfully gathering the shells to make necklaces, arm rings, and waist belts for Nomalanga’s protection.

In “Picking Shells. 1979″ has a strong diagonal composition, with the main section of the artwork depicting a diagonal beach, with fish jumping. At the top and bottom are rows of seated girls that look like mirror images of each other.

One unusual aspect of the artwork is that the top row of girls is upside down while the bottom row is the right way up. This might make us think about how water reflects the real world. It could also be a reference to the parallel world beneath the waters where spirits and ancestors live.

Allina sometimes add little 3D elements into the tapestries, weaving these materials onto the tapestry.

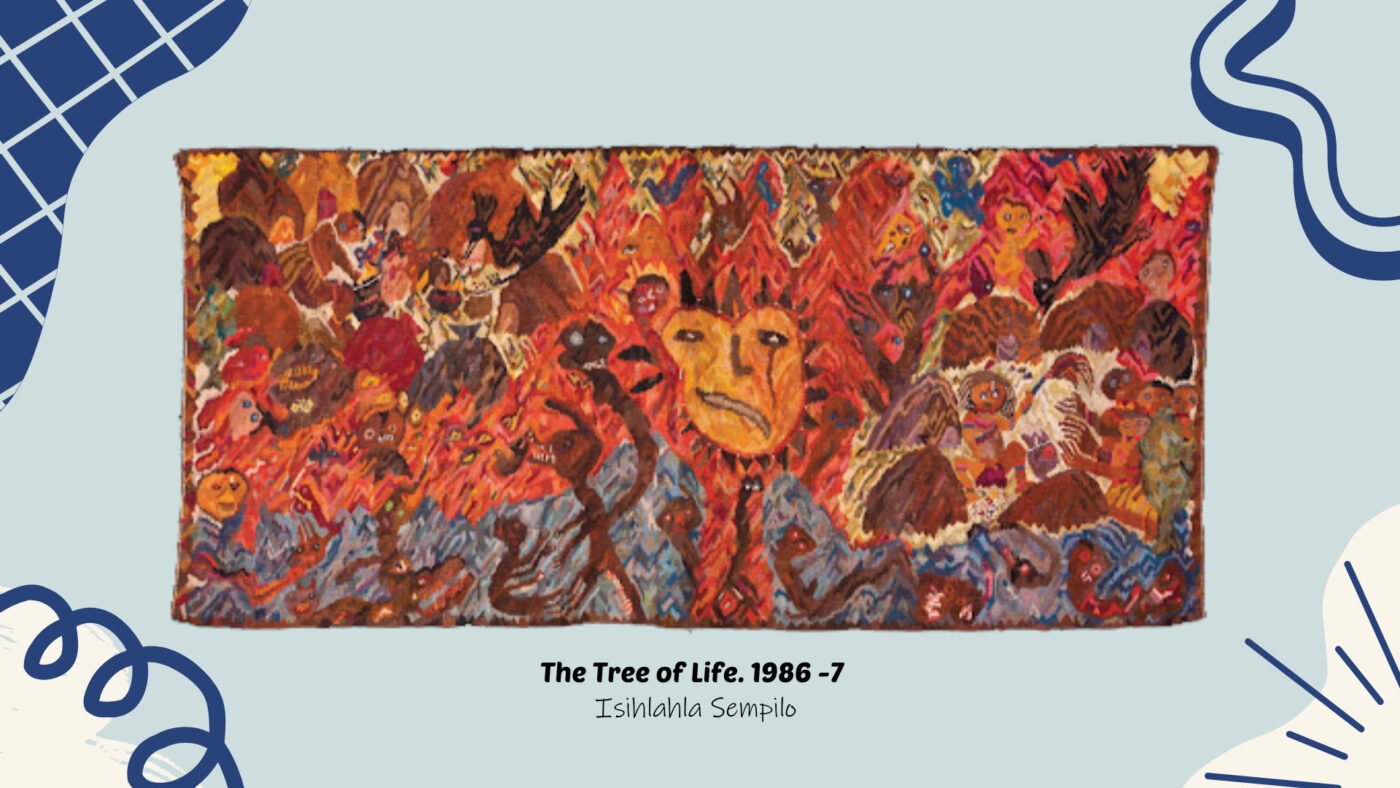

In one of her artworks called “The Tree of Life,” she weaved real divination materials like shells, bones, and beads onto the tapestry. It makes the Sangoma’s Muti bag like more real and draws our attention to its importance. The sangoma’s muti mixture, consisting of shells and bones, helps to neutralise the evil deeds and brings some relief to the village. So, shells have protective powers, and Ndebele incorporates them into her artwork to show their importance.

5. Use of Pattern & Repetition

Allina Ndebele often uses pattern and repetition in her tapestries. Pattern is when an artist uses the same design, shape, or motif over and over again in their artwork. It creates a sense of order, rhythm, and harmony. Repetition, on the other hand, is when an artist repeats a specific element throughout the artwork.

It also creates visual interest and draws our attention to certain parts of the artwork. When we see something repeated, our eyes are naturally attracted to it. Think of it like a catchy song with a repeated chorus that gets stuck in your head. In the same way, pattern and repetition can make an artwork more memorable and captivating.

Pattern and repetition can also create a sense of unity and cohesion in an artwork. By repeating certain elements, artists can tie different parts of the artwork together and make it feel balanced and harmonious. It’s like having a common thread that connects everything in the artwork. In the artwork Tree of Life, Ndelebe binds various items and figures together with a strong chevron pattern, resembling flames.

Another reason why artists use pattern and repetition is to evoke certain emotions or moods. For example, a regular and orderly pattern might make us feel calm and relaxed, while a more chaotic and energetic pattern might make us feel excited or restless.

Artists can use these visual techniques to communicate their ideas and feelings to the viewer. In the tapestry Drought, we can feel the heaviness of the suns’ heat bearing down on the earth through the repetitive triangle shapes.

The animal’s anxiety is also felt by repeating them, placing them close to each other in jagged shapes. In The Two Lions and the magic pots, the repetitive pattern in the background almost makes the bird’s incessant squawking audible. Creating a sense of disorientation and bewilderment for both the viewer and the lions.

Ndebele’s designs, have many curves, zig zag paterns and repeating geometric shapes. It required a lot of time and skill to make these complex patterns on a loom. She had to fasten each element of the design to the adjacent shape. This requires a lot of effort and skill to make sure the strands are tightly woven together.

6. Use of Colour

In Allina’s work, colour plays a significant role in creating beautiful and vibrant artworks. Peder Gowenius always praised her “good eye” for colour.

Allina modestly mentions that she has always adapted her work and ideas to the available colours and off cuts she had. Despite limitations, her tapestries showcase an exceptional understanding and application of colour.

She sometimes implemented suttle tones of colour, for example, in the tapestry called “Picking Shells,” the beige background alone consists of 13 different shades, and the waves are brought to life with 20 different tones of blue. In “The Tree of Life” tapestry, she portrays the sun with streaks of colour on its face, using as many as 22 different shades to represent the folds of skin.

To creat various shades and tones of a colour, Allina had to carefully tweak her dying process. More rinses created lighter shades, less rinsing kept a colour more vibrant.

She also loved vibrant bold colours. In her tapestries featuring the rain goddess, she uses intense reds and brown to highlight the power of this natural force.

Allina Ndebele’s tapestries showcase her skilful use of colour. She combines various shades and tones to create depth, texture, and visual impact in her artworks. The range and precision of colours she employs demonstrate her talent and enhance the overall beauty of her tapestries.

7. Central Composition & shallow depth of field

Allina often makes use of central composition in her tapestries. By placing the object in the middle, it becomes the main focus, and our eyes are naturally drawn to it. It’s like the star of the show! This also creates a balanced and symmetrical feel to the composition.

Allina’s figures appear flat without a strong sense of depth. Instead of using techniques like perspective to create the illusion of depth, she focused on creating clear and easily recognisable images. She wanted her art to tell stories rather than imitate the three-dimensional world.

She often used size to depict importance. It is a technique called “hierarchical proportion,” which means that the size of a figure or object in the artwork indicates its importance or social status. The more important or powerful the person or object, the larger it would be depicted in relation to others. This technique helped her communicate the importance of certain characters or elements in her artworks.

That concludes the 7 Characteristics of artist Allina Ndebele’s tapestries. I am so excited to finally tell you the two stories depicted in two of her most famous artworks.

Two Tapestries you should know by artist Allina Ndebele

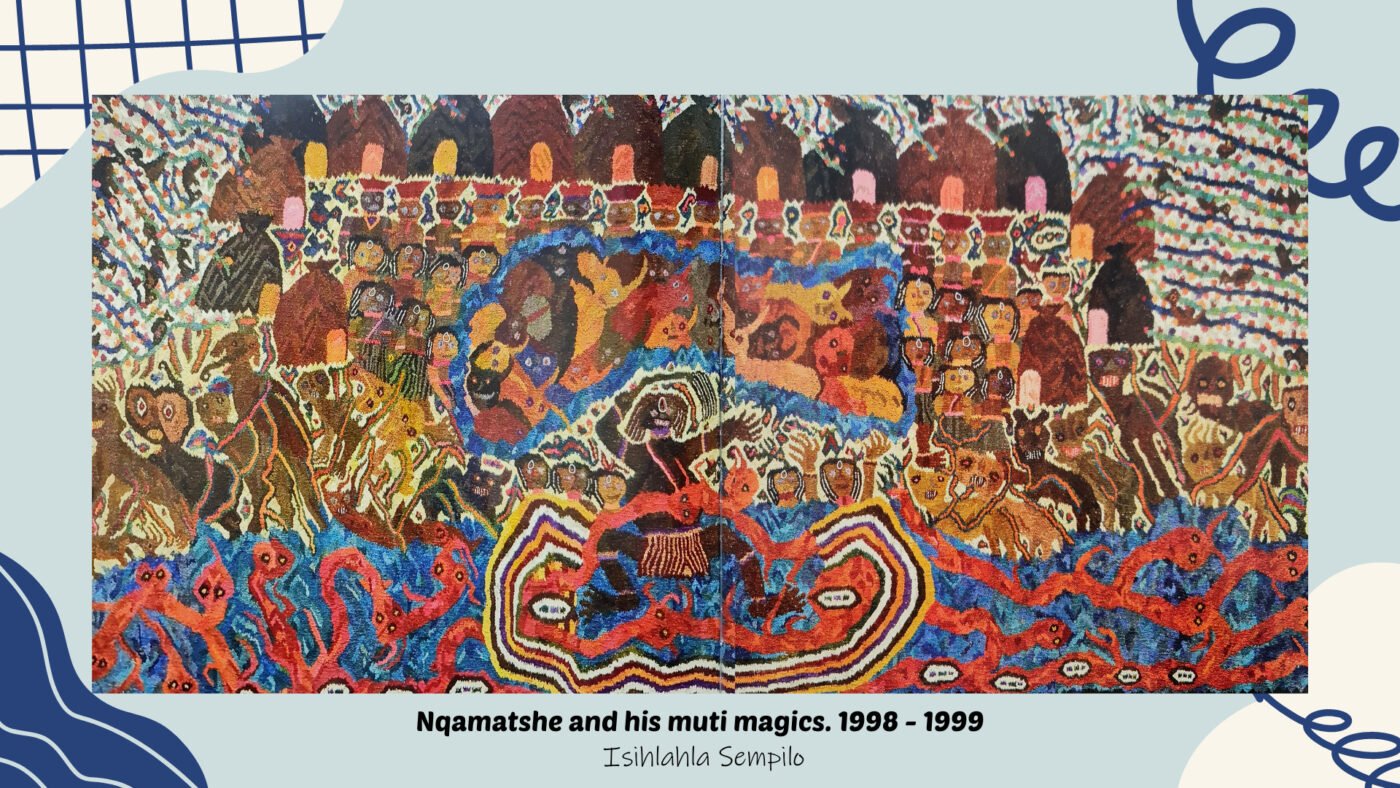

1. Nqamatshe and his muti magics. 1998 – 9.

Ndebele’s biggest artwork is called “Nqakamatshe and His Muti Magics,” which was commissioned for the MTN Art Collection in 1999. It’s a very large piece, measuring 2m x 4.5 m, and it took her 11 months to complete.

The story is about a traditional healer and diviner named Nqakamatshe. He lived far away from the community, close to a big river. In the river lived a snake-like creature called Mamlambo. It was a cryptid, part snake, park fish. It was believed that Mamlambo could bring luck and wealth to anyone who could control it. However he was also a vicious carnivore that could kill all living things.

Many people came to Nqakamatshe for help, but some women came not because they were sick, but because they wanted a special potion to make their husbands or future husbands love them more. When three beautiful ladies asked him for the potion, Nqakamatshe liked them so much that he made them fall in love with him and kept them with him.

When the husbands of those ladies found out, they were very angry and went to attack Nqakamatshe’s home to kill him. But he was warned about their plan, so he had the snake, Mamlambo eat them instead. Later, when Nqakamatshe saw some round objects that looked like large eggs on the river bed, he asked what they were, and he was told that they were the skulls of the men who came to attack him. The snake appeared and started swimming angrily in the river.

Nqakamatshe his trainee sangomas, were overcome with terror. Nqakamatshe’s ancestors were enraged. They started speaking in a loud voice and told Nqakamatshe that he had misused his magic powers. As punishment, he was stripped of all his magic and banished to live at the bottom of the river forever, and so peace returned to the village. In the tapestry, we see Nqakamatshe being sucked into the river.

We see just how much Nqakamatshe has fallen with this punishment by looking at the homestead he leaves behind. It is well-ordered, has many wives and contains a kraal well stocked with cattle. Outside of the homestead, we see the chaos of the wild teeming with spiritual creatures.

This story teaches us important lessons about greed and abusing power. It shows that when people act selfishly and harm others, there are consequences. It serves as a warning for anyone who might be thinking of behaving in a similar way.

2. The Tree of Life / Isihlahla Sempilo 1986 – 7.

This is not a story that Allina heard from her grandmother. It is a story formed from her own lived experiences and imagination. It is not about a genuine physical tree as we know it. The Tree of Life in this tapestry refers to a form of energy that contains all life.

This tree, or energy, seems to bear the face of a sun, with its branches stretching out over the tapestry represented as all consuming flames. The life force seems to flow through all the elements binding them together. The sun’s face is divided into two. The right side is tearful and sad while the left side is happy, depicting the duality of life.

You see the sun is is busy witnessing the humans disobedience unfolding in front of it. The tapestry tells a story set in Allina Ndebele’s home village, Egazini. Long long ago some people in the village loved each other and others hated each other. Soon the witch doctor in the village became jealous of his neighbour. He desired both of his neighbour’s beautiful wives. And so the witch doctor devises an evil cunning plan.

The jealous witch doctor summoned evil forces from the river to help him get rid of his neighbour. We see the Tokoloshe rise up out of the river and other evil spirits frantically slithering around. The tokoloshe has sharp teeth, even his one hind leg grows teeth. The harmony of the community life is instantly disrupted. The Tokoloshe infiltrates the house of the neighbour where the two wives live. You see the witch doctor has instructed the tokoloshe to poison the neighbour’s food.

In addition, he also summoned, Thekwane, the Hamerkop Bird, known as a lightning bird to strike their house. We see the hamerkop bird being repeated in the tapestry, on the left he sweeps in low above the homestead. Hamerkops are feared in Zulu culture, they symbolise trouble and are agents of misfortune.

Unfortunately, the two wives die from the lightning strike, the children and father survive. However, they do become sick from the poisoned food.

Scattered on the tapestry are the faces of the ancestors. They are waiting for the villagers to ask them for help by performing rituals. With all this chaos going on the community summons another witch doctor to identify the cause of the evil. On the left side of the tapestry we see this new witch doctor throwing bones. The witch doctor also uses her staff, the tail of the buffalo to feel the evil. She successfully identifies the culprit and we see the community cheering her on.

In the tapestry Allina attached small white beads all around the sun’s face. This represents the intricate umyeko hairstyle that a sangoma typically wears. These white beads plaited into dreadlocks are for luck, fortune and protection. It seems that these beads have worked for the Sun in this tapestry. The sun is flanked on both sides by two newborns born from the water, which represents a new beginning.

The tapestry doesn’t show the actual punishment of the first witch doctor, nor the moment of death of the two wives. Some parts of the story are left untold, hiding the worst horrors from the viewers’ eyes. Instead, it focuses on the cleansing of the affected homestead and the expulsion of bad omens.

In crafting the narrative for this tapestry, Ndebele blended various elements. She combined customary Zulu concepts, her own personal ideas, and a Christian symbol, as suggested by the title. The Tree of Life holds significance in both the Old and New Testaments of the Bible, which Ndebele was familiar with due to her upbringing on missions.

This is the only tapestry that Allina did actually make a planning sketch for. She had applied for a second visa to visit Sweden again and was awaiting a response from the Apartheid government. Unfortunately, her visa was denied. She was devastated by the news and stopped weaving for a while. She made a quick sketch to capture her idea, so she wouldn’t forget when she was ready to weave again.

Interestingly, when Allina eventually resumed working on the tapestry, she didn’t need the sketch anymore. She could visualise the pictures and colours in her mind once again, showcasing her remarkable ability to create and bring her artistic vision to life.

Conclusion

Artist-weaver Allina Ndebele has been creating beautiful tapestries for over thirty years. Most of her work was created after she left The Rorke’s Drift Arts and Craft Centre. She takes inspiration from traditional Zulu symbols and ideas for her work. You can now find Allina Ndebele’s tapestries in important art galleries and collections. Each piece is not only a valuable part of South African heritage but also a special tribute to the incredible determination of an artist who faced many challenges to share her art with the world.

Sign off.

I am artist Lillian Gray, and I love teaching art and art history. Remember to subscribe and ring the bell to get notified when a new video is released.

This is a reminder that you can shop various worksheets for all ages online on our TpT website. Connect with us on social media, and let us know what video you want to see next.

Until next time.

BUY OUR RORKE’S DRIFT WORKSHEETS

Worksheet pack that includes notes and fun activities. Ideal for art students and history students to learn more about the Rorke’s Drift Art Center

Resources

Allina Ndebele: Weaver-designer. 1985. Exhibition catalogue for ‘Tapestries by Allina Ndebele’, 6 November–6 December 1985. Pretoria: Pretoria Art Museum.

Berglund, A-I. 1989. Zulu thought patterns and symbolism, revised edition. London: Hurst and Company.

Biyela, N.G. 2009. Popular predictor birds in Zulu culture.

Hobbs, P. 2004. Shifting paradigms in printmaking practice at the Evangelical Lutheran Church Art and Craft Centre, Rorke’s Drift, 1962–1976. MA thesis, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.

Hobbs, P. and N. Leibhammer. 2004. Allina Ndebele and the increasing picture. In Veterans of KwaZulu-Natal, ed. J. Addleson. [CD Rom]. Durban: Durban Art Gallery.

Hobbs, P. and N. Leibhammer. 2011. Water and space: Unravelling meaning in the weavings of Allina Ndebele. de arte 83:5–20.

Hobbs, P. and E. Rankin. 2003. Rorke’s Drift: Empowering prints. Cape Town: Double Storey Books.

Hofmeyr, I. 1993. ‘We spend our years as a tale that is told’: Oral historical narrative in a South African chiefdom. Portsmouth: Heinemann; Johannesburg: Wits University Press; London: Currey.

Ndebele, A. n.d. The Tree of Life: Tapestry story. Transcribed by Nokuthulo Ndebele. Caja Stort files, Eshowe.

Ndebele, A. 2013. Personal interview with the author, 15 December, Swart Umfolozi. Ndebele, A. 2013/14. Telephonic interviews with the author, 15 December–20 April, Swart Umfolozi.

Roberts, A. 1969. Birds of South Africa. Revised edition, seventh impression. Cape Town: Trustees of the South African Bird Book Fund.

Tree of Life. 1965. Isihlahla Sempilo 1(September/ October):1. Philippa Hobbs files, Johannesburg.

Zulu, B.S. 2002. From the lüneburger heide to northern Zululand: A history of the encounter between the settlers, the Hermannsburg missionaries, the amakhosi and their people, with special reference to four mission stations in northern Zululand (1860–1913). MT thesis, University of Natal, Pietermaritzburg. http://brage.bibsys.no/xmlui/bitstream/ handle/11250/161941/Zulu_mthesis_2002. pdf?sequence=1 (accessed 10 January 2014).