No products in the basket.

Art History

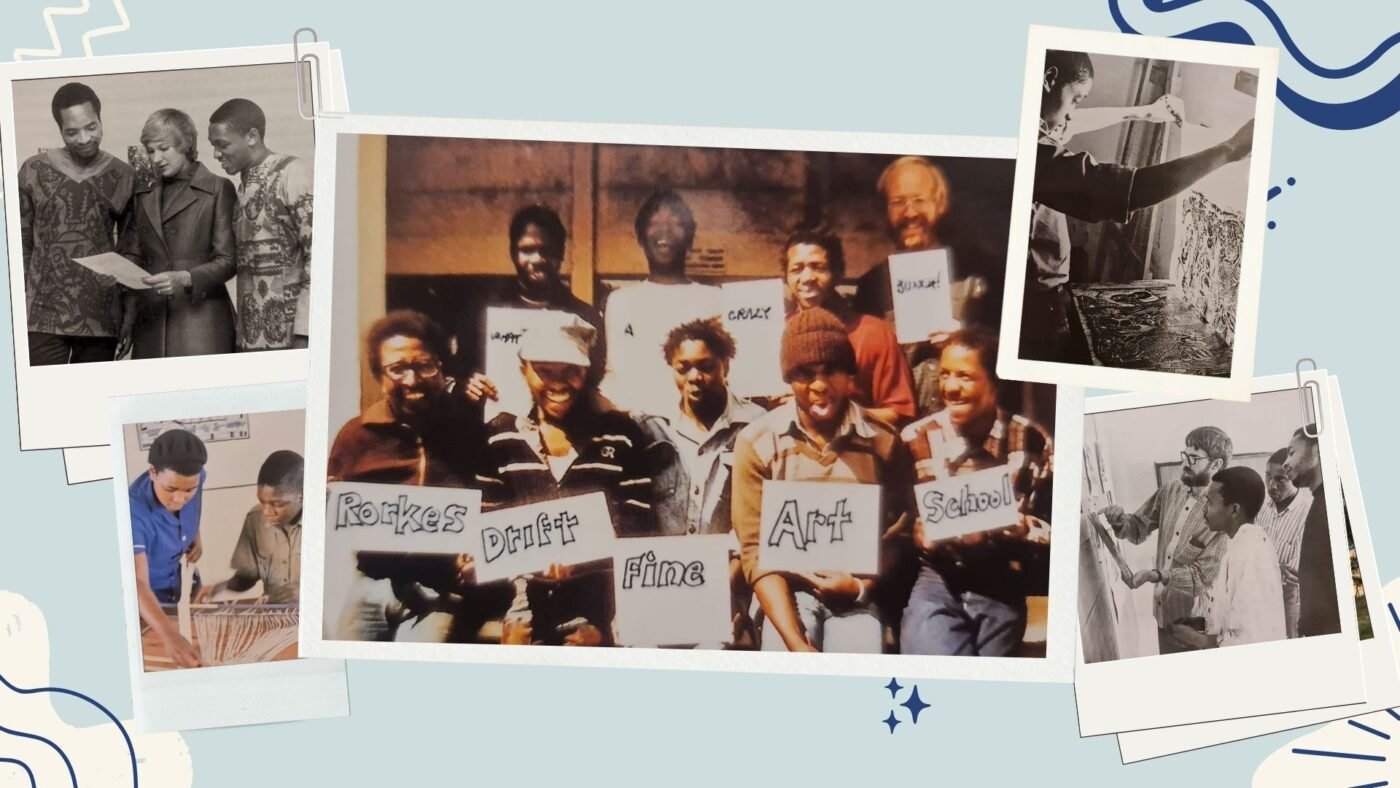

Namibian Artist John Muafangejo, who trained at Rorke’s Drift Art and Craft Centre

Intro

Hi, I am artist Lillian Gray, and today I would like to introduce you to Namibian Artist John Muafangejo (1943 – 1987).

John Muafangejo is often thought of as a South African artist. However, he is, in fact, a Namibian. People tend to think of him as South African because he is best known for studying at the Rorke’s Drift Art and Craft Centre in Kwa-Zulu Natal, South Africa (1968 – 69).

With Azaria Mbatha, Allina Ndebele, and Gordon Mbatha, John Muafangejo is one of the most celebrated artists from The Rorke’s Drift Arts and Craft Centre. His style is often seen as Rorke Drift’s trademark style.

This is a quick reminder that you can shop various worksheets based on Rorke’s Drift on our TpT Store. They are specifically designed for various ages and are fun to do.

Zeitgeist

Before we start, we need to cover the Zeitgeist that John Muafangejo lived in. Zeitgeist is a fancy word that simply means Spirit of the times. What was life like when Muafangejo was alive? During his life, Namibia was under South Africa Rule and known as South West Africa. The National Party of South Africa imposed its Apartheid laws, including racial classifications, on Namibia. In the later 20th century, uprisings and demands for independence started. Following continued guerrilla warfare, Namibia obtained independence in 1990. So as you listen to this story, bear in mind the unjust rules Muafangejo faced throughout his life.

Despite all odds, this boy, from a traditional rural upbringing suppressed by the discriminatory rules of Colonialism and Apartheid, became an internationally respected artist. Today he is honoured and celebrated for his unique, bold style used in his linocuts, woodcuts and etchings.

In this video, we will look at the five characteristics of John Muafangejo’s style; the lino cut printmaking process, the subject matter of John Maufangejo’s art and end with three artworks you need to know about this respected Namibian artist.

But first, let’s delve into his story and discover what makes his art remarkable.

Biography

John Muafangejo grew up in rural southern Africa in a traditional environment. John’s father was a wealthy Kwanyama chief from the Ovambo Tribe. The Ovambo people reside in the flat grassy plains of northern Namibia and southern Angola, sometimes called Ovamboland.

The Ovambo tribe practices Polygymy, which means a man can have more than one wife. The first wife is seen as the senior. His father had eight wives and 18 children. After his father passed away, his mother, one of his eight wives, wasn’t entitled to an inheritance and was left destitute. She left Southern Angola for Namibia, where she went to live at a Mission Station and converted to Christianity. The 12-year-old John had to follow his mother but found it very upsetting to leave the kraal where he grew up. He joined the small missionary school and learned to read and write, the only family member to do so.

His talent for drawing was noticed at the small school, and an uncle encouraged him to draw from everyday life experiences and to develop his style.

After school, an American priest (Mallory) helped Muafangejo with the application to the Arts and Craft Centre of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Rorke’s Drift, Natal in South Africa.

Now Rorke’s Drift Art and Craft centre was a special place. It is often described as “the most famous indigenous art centre in South Africa!” At the centre, Muafangejo came into contact with different artistic techniques. The centre is world-renowned for its Pottery, Tapestries and Printmaking.

It offered arts and craft training for black people during the Oppressive Apartheid Regime. Apartheid policies denied a formal education to black artists and crafters. Rorkes Drift taught craft and established a Fine Art School for people of all races. It created a unique space where people of all races were mixed to share ideas, insights and skills. Not only were people from different races but also from African and other International countries.

This created a unique fusion. European Skills mixed with African stories and styles. However, it is even more remarkable that European teachers at the school were careful not to influence their African students too much. They wanted them to maintain their Africancity.

Muafangejo trained at Rorke’s Drift from 1968 to 1969. However, he produced a number of tapestries and paintings while at Rorke’s Drift, Muafangejo is known almost entirely as a printmaker. Under the influence of his teacher, Azaria Mbatha, Muafangejo developed his artistic ability and preference for linocut as a medium.

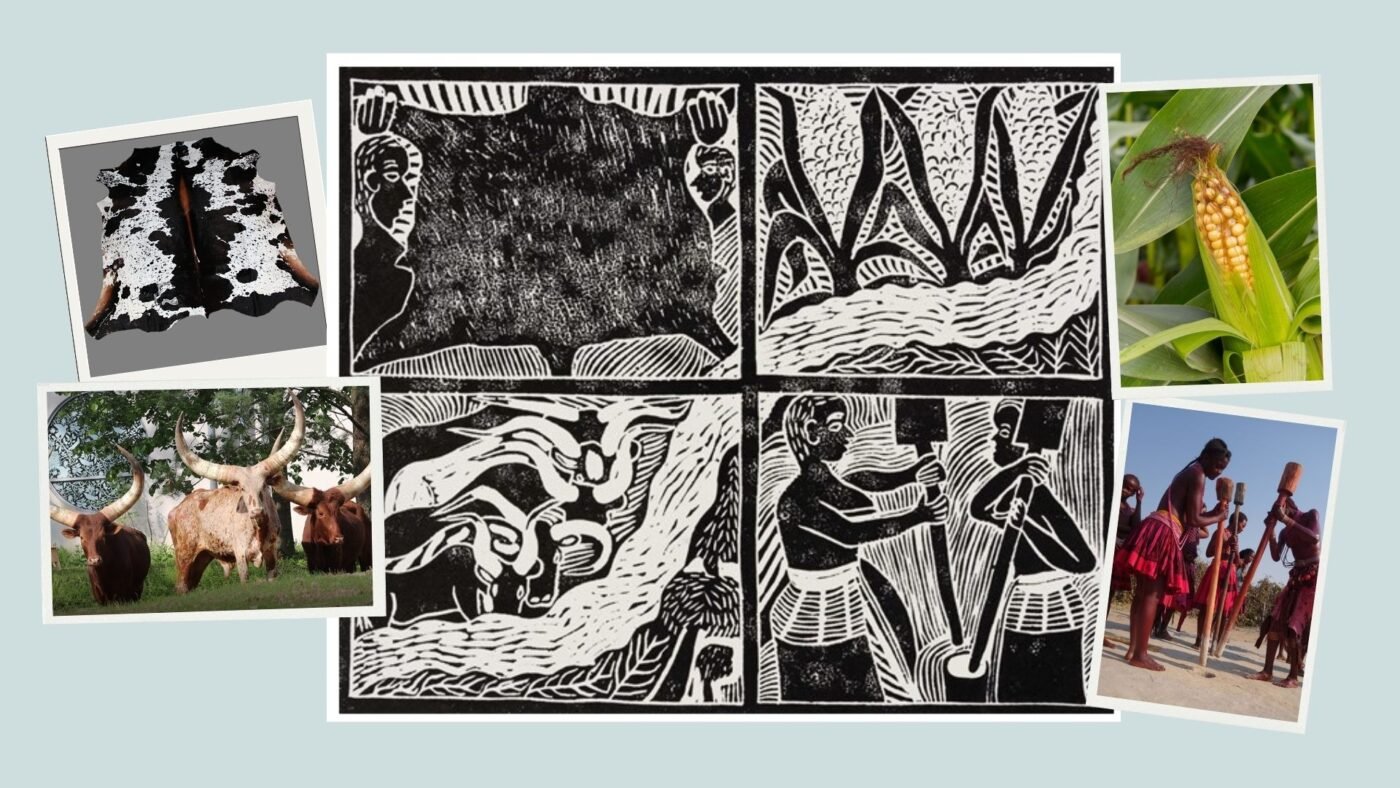

Why Lino? Well, two possible reasons. One, the skills Muafangejo learned as a young boy was similar to the technique and skills required for Linocut. In his traditional environment, the men were expected to be cattle herders, hunters and providers, but they also had to be creative. They created domestic utensils from wood, drums, leather garments, pottery, baskets and weapons such as spears and knobkerries.

On many of the wooden objects, they added design elements in poker work or pyrography. Two, Lino was easy to transport around and do almost anywhere. It was easy for art students to take their linoleum sheets with them to their dorms and keep carving at night while chatting. One also does not need a fancy printing press; you can do a beautiful lino print simply using a teaspoon.

When Muafangejo had access to the necessary equipment and materials, he produced an impressive body of woodcuts and intaglio prints. In intaglio, he used etching and was particularly adept in using drypoint – where the image is scratched directly into the plate.

Despite the fact that Rorke’s Drift is a super special and unique place for its time, Muafangejo’s life experience at the art centre was extremely difficult. Muafangejo was an intense and sensitive individual. He thought deeply about various matters and expressed and questioned them through his art. He could not speak isiZulu or Sesotho, and English was his third language. (His first language was OshiKwanyama) He experienced feelings of isolation and severe depression.

His intense focus on his artworks led to nervous exhaustion at the end of his first year at Rorke’s Drift. He suffered from manic depression, for which he had to be hospitalised. He completed his course at Rorke’s Drift in 1969 and returned to Namibia – the country he loved deeply – the following year. From 1970 he taught art at his former school in Odiba.

5 years later, he returned to Rorke’s Drift to work for a year as an “artist in residence”. Although he suffered greatly due to manic depression, he always tried not to impose this on family and friends but took his medicine and locked himself in his room until he could cope with work and life. In 1977 he moved to Namibia, where he bought a house outside Windhoek.

Muafangejo’s international breakthrough when he exhibited in London. An Art critic rated his linocuts “consistently the best of all the modern African masters.” Various historians expressed the same opinion. Invitations to other exhibitions and write-ups on his work followed.

Muafangejo received recognition for his outstanding printmaking representing South Africa at the Sao Paulo Biennale in 1971, The Museum of African Art in Washington DC in 1974 and the Brooklyn Museum of Art in New York in 1976. During the 1980s, his work was exhibited regularly in the United Kingdom, Finland and Germany. He visited Finland in 1981. A trip that possibly united him with his teacher Azaria Mbata who had left South Africa and been living in Sweden since 1970. He was a guest artist at the National Arts Festival in Grahamstown in 1987, the year of his death.

- 1969 Contemporary African Art Exhibition, Camden Arts Centre, London

- 1972 São Paulo Biennial

- 1975 Arts Centre, Durban (solo exhibition)

- 1976 Black South Africa: Graphic Art, Brooklyn Museum, New York

- 1980 John Muafangejo Graphic Art (solo exhibition), Bullankulma Art Gallery, Helsinki

- 1987 Black Art – John Muafangejo and Peter Clarke, IFA Gallery, Bonn

- 1987 National Arts Festival, Grahamstown (retrospective)

Muafangejo died in his house just outside Windhoek of a heart attack in 1987. He had yearned for Namibia’s independence but did not live to see it happen. However, one of his dearest wishes came true one year after his death. The John Muafangejo Art Centre was opened. It offers art classes for aspiring artists with previously disadvantaged backgrounds.

Let’s take a closer look at 5 characteristics of John Muafangejo’s unique art style.

His Style

1. Expressive and Stylized

Muafangejo’s style is characterised by simplified shapes with an expressive version of reality. It is a highly decorative pattern-like style with the repetition of lines and shapes. This created a strong rhythmic effect.

Muafangejo’s work could be classified as Realism with a capital R. Not realism as in realistic; his work is quite stylized. But rather Realism, which depicts society and daily occurrences without pretence. His artworks is can also be associated with German Expressionism. Because the emotion or the narrative is more important than depicting everything in minor details, he also sometimes distorts figures to aid the communication of emotion.

2. Shallow depth of field

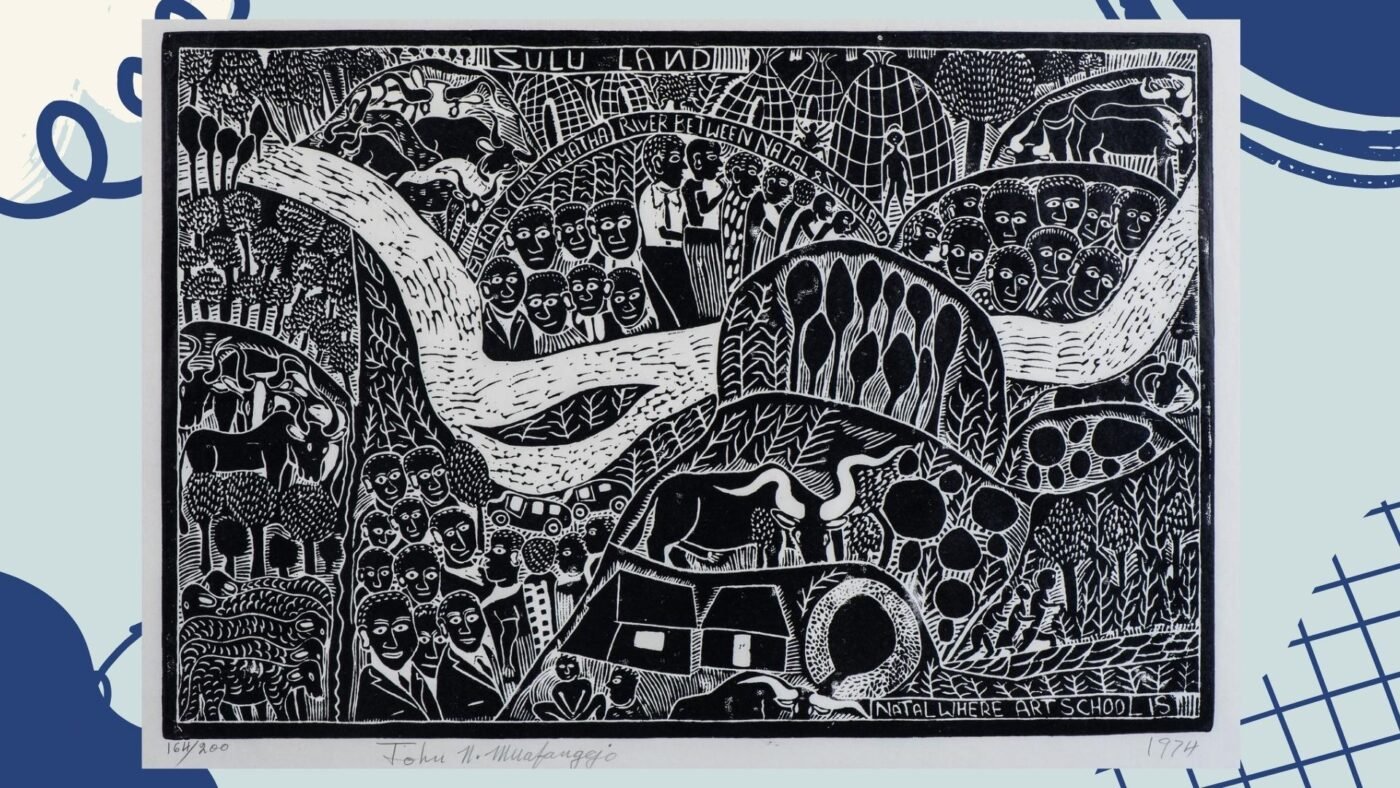

He implemented a shallow depth of field in his artworks and lacks depth and the use of a vanishing point. Most works are completed with a two-dimensional decorative background.

3. Narrative

There is always a strong narrative component in his work. When asked about his style, he said “It is a teaching style” it is intended to communicate clearly to the viewer. He conveys a story literally and figuratively in black-and-white. He often captures a specific dramatic moment of the story.

Many have described Muafangejo’s work as naive, but they often include complex narratives inside basic shapes. A circle, with an angle and a cross, inside a rectangle block. They are meant to be read in panels such as comic, or tryptic. He, in fact, produced work which comments with subtlety and insight on the world around him.

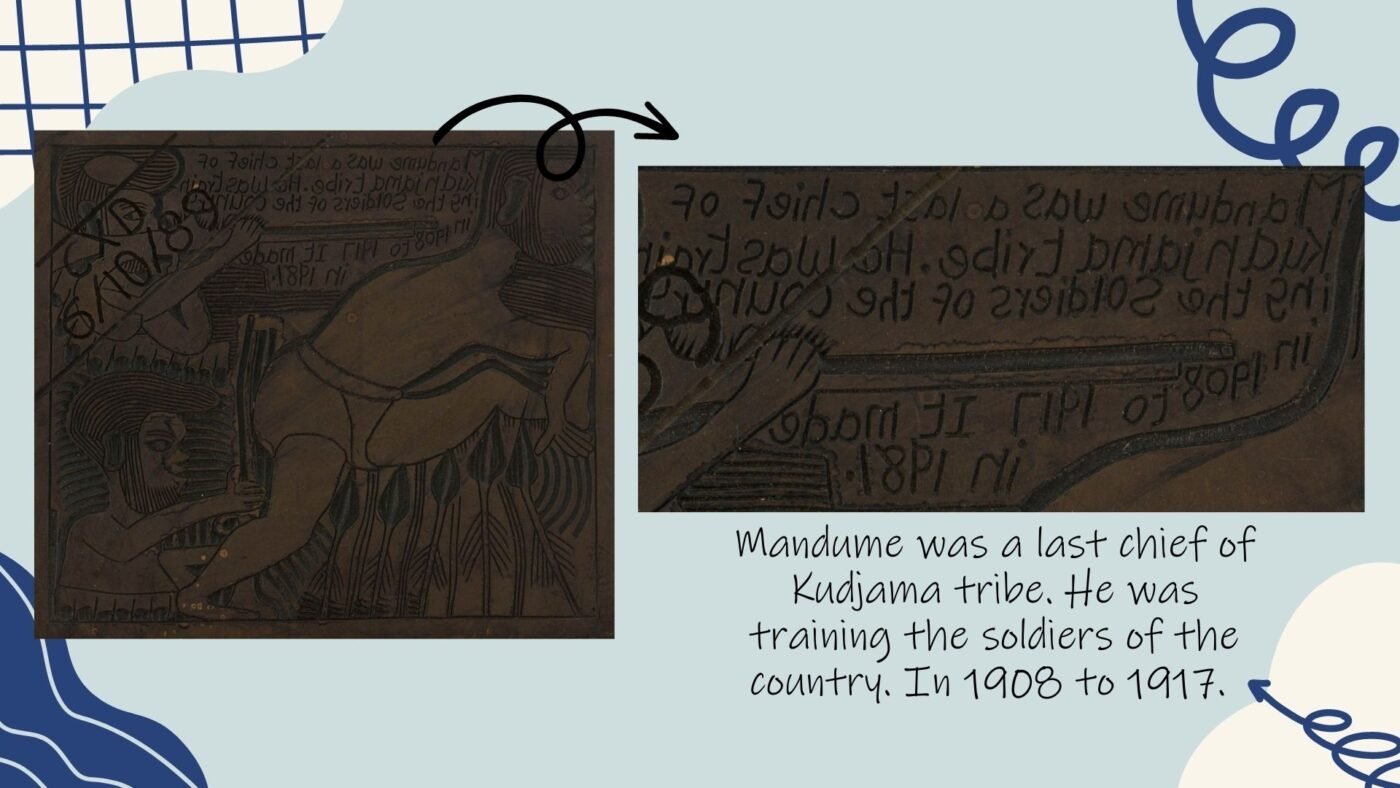

4. Use of Text

John Muafangejo was an artist that wanted to be understood. He often describes and explains his narrative by adding text to the image. His English was not always eloquent or correct, as it was not his first language.

In 1985 he said, “I am the only educated one [of my family], so the responsibility is mostly mine. I cannot go overseas anymore; there is no money.”

Much of the text in his artworks is English and so his art was aimed at white viewers. He presented the European Audience with a dignified view of black’s everyday lives. Changing the perspective of the gaze….

The text confirms that his works are documentations of actual events and incidents rather than stories. Text at times becomes so important that the print resembles a page from a medieval illuminated manuscript.

5. Use of Colour

Predominantly Muafangejo’s art is done in black and white. There is a stark contrast found in the linocut prints. Depending on the specific artwork, Lino cuts’ black and white colours could symbolise a few meanings. One meaning is the racial tension at the time in both Namibia and Apartheid South Africa. Race determined the path people’s lives were likely to lead. The black and white printing colours could also represent the struggle between good and evil. The colours could also refer to the duality that is part of life and underlies all human activities and events.

When asked about the lack of colour in his work, John Muafangejo stated that he enjoyed creating black and white artwork since “it does not tire the eyes of the viewer.” Allowing them to engage with the story longer.

Linocut Printmaking Process

I’m going to take you through the process of the lino printing technique. First, you draw your desired picture onto your lino sheet. With your lino tools, carve out the areas you want to keep white. So it is the opposite of drawing. You are carving the areas around the black lines, the negative space. Once you are done carving, apply ink with a roller.

You carefully place the lino sheet onto a piece of paper. Now you need to apply lots of pressure. You can do this with either a printing press or a teaspoon. The ink will be transferred from the sheet to the paper. Carefully remove the lino sheet to reveal the result. Now you have your first print.

As you can see, this printmaking process generates a mirror image. So when you carve text, you have to carve it backward.

The wonderful thing about Lino is that you can keep printing the same image multiple times. Professional artists usually decide how many prints they want to make of a specific design. For example, 50. Each print will then be number 1/50, 2/50, 3/50 and so forth. John Muafangejo was a master printer. He kept a meticulous record of everything he produced.

He was responsible for limited print editions. You’ll see the cxd on the top left corner and the date, which is essential because they can never be used to reprint this particular design. This is vital to art investors as it prevents fakes from entering the market.

Subject Matter of his artworks.

John Muafangejo’s oeuvre of work is of an autobiographical nature and reflects the state of his mind and his daily experiences, like a diary. They include the following categories.

1. Tribal Life

Many of his artworks provide us with essential snapshots of Ovambo traditions and rituals. This culture is under threat. Christianity arrived among the Ovambo people in the late 19th century (the 1870s) Ovambos predominantly converted and identified themselves as Lutheran Christians—the influence of the missionaries not only related to the religion but cultural practices.

For example, the typical dress style of the contemporary Ovambo women, which includes a head scarf and loose full-length maxi, is derived from those of 19th-century Finnish missionaries. The Ovambo now predominantly follow Christian theology, prayer rituals and festivities, but some traditional religious practices have continued. Most weddings feature a combination of Christian beliefs and Ovambo traditions. With his artworks, John Muafangejo keeps the memory of the Ovambo tradition alive.

2. Church Life

John Muafangejo came from a rural background and had to make his way in the Western art world. His family was part of rural African culture, yet he became a deeply devoted Christian, with this Christian faith becoming an essential aspect of his life.

He struggled to reconcile the brutal politics of the day with Christianity. Muafengejo’s art is deeply religious. His work portrays a message of deep human feelings and hope and an intense belief in the dignity of all human beings. He often depicts the Church’s social role in resisting and opposing an inhumane and unjust Apartheid regime.

3. Social conditions

John Muafangejo was not a protest artist. However, he did comment on and record the social inequalities and conditions in his art as he recorded everyday life.

4. Local Historical events

One of Muafangejo’s most famous artworks is The battle of Rorke’s Drift – 1981.

This artwork was inspired by a teaching aid used at Rorke’s Drift art school. Adolphe Alphonse de Neuville (1835-1885) Defence of Rorke’s Drift, 1880, oil on canvas. Alphonse was a noble artist that was paid by the British to depict the battle. In Alphonse’s work, the British are depicted as heroes. Notice the crates in the foreground of the painting.

The Battle of Rorke’s Drift was one of the favourite subject matters of the students at Rorke’s Drift Art and Craft Centre. They enjoyed depicting their local history. John Muafangejo created his own version of the painting done by Adolphe Alphonse de Neuville. Muafangejo reverses the entire composition. In his artwork, the Zulu warriors are active and dynamic. They corner the British in a crate, or maybe the small hospital building.

Natal Where the art school is – 1974

Bird’s eye view of where Rorke’s Drift is located. Cutting through the picture is the river with a little island. That’s where the actual drift was, and easy to cross the river with a wagon. In the bottom right-hand corner, we see the text where the art school is. This refers to these two tiny little buildings in the foreground. He shows that art is part of the community. In the print, we see daily activity, cattle herding, huts, sheep, and farming.

5. Personal Experiences

Muafangejo’s work is filled with touches of humour, experiences or observations. Such as, Lion kills in a funny way. The work known as The lucky artist – 1974, was conceived after the announcement on Radio Owambo that Muafangejo had won a silver cup for an exhibition.

Muafangejo did not know for which exhibition he had won the award but decided to celebrate by making this print. This was just as well, for in the end, he did not receive a cup at all! Although very disappointed, Muafangejo typically does not show this in his print.

6. Travelling

John Muafangejo travelled pretty extensively in what is now Namibia, in South Africa and on several occasions to Europe, the U.K. and Scandinavia. The Swedish missionaries who ran the Art and Craft Centre at Rorkes Drift made much of this possible. Wherever he was, he usually depicted something of his experiences in his artworks, keenly observing life and the people around him with his typical social commentary and engaging sense of humour.

He recorded his travel experiences in linocuts such as British Airways traveling by plane. Holidays traveling by bus and from Finland, a small ship was going to the small island. This work is called Snow was making the artist fall down twice in Finland – 1981.

He depicts himself in the foreground, having fallen flat on his back, one arm and one striped trousered leg stiffly and comically up in the air. For some traveling from blazing hot Namibia to Finland, and experiencing the slipperiness of snow, must have been quite a funny ordeal.

7. Animals

John Muafangejo looked after cattle in his early years and through this, he became aware of animals, their beauty and their danger. In his artworks, he depicts the tenderness and respect for animal and human life showing that we are not so different in Africa.

Artworks you should know by John Muafangejo

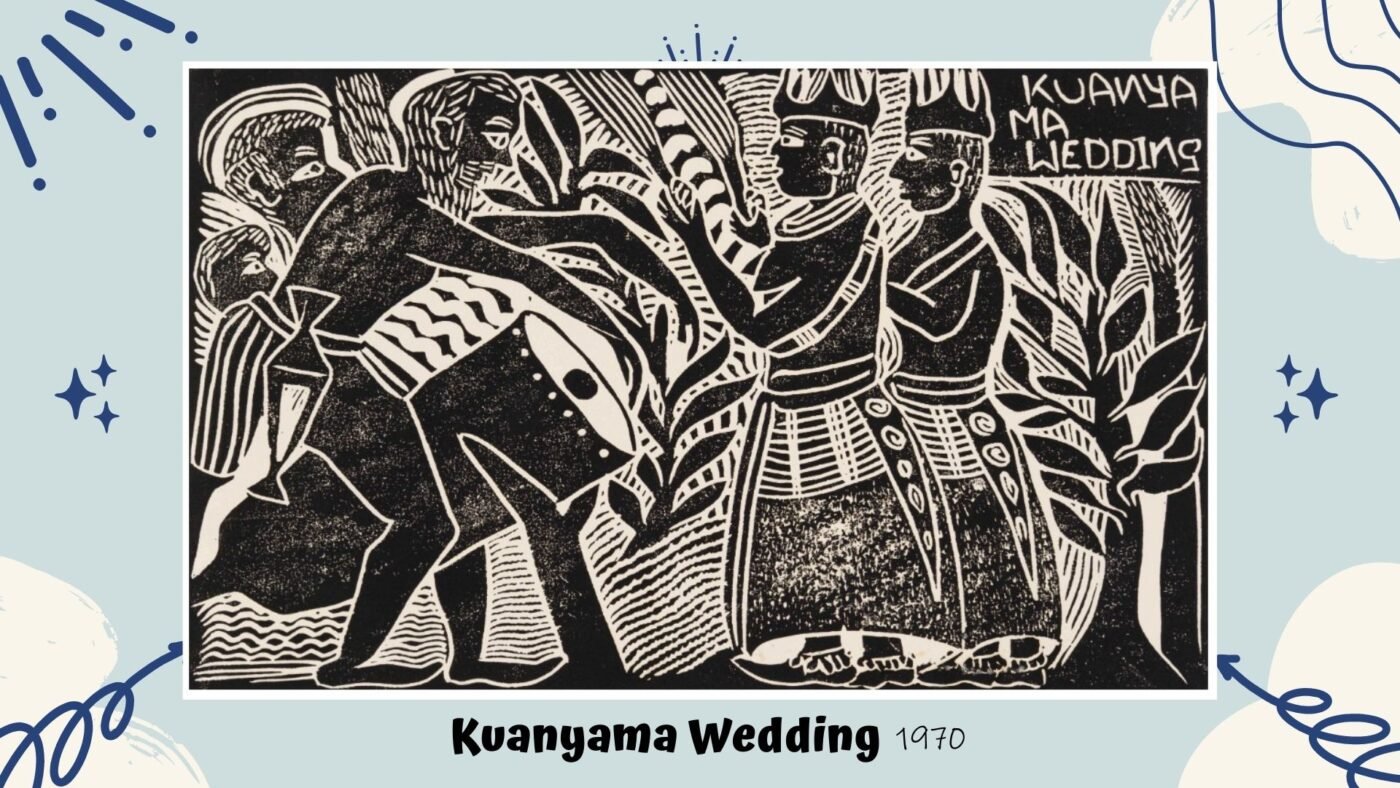

Kuanyama Wedding. 1972

In the artwork Kuanyama Wedding – 1972, Muafangejo depicts the ancient wedding traditions of his community. He depicts the topic of Ovambo weddings in various artworks. This gives us an indication of how important this event was within the traditional environment. The work creates awareness of the complexities of tribal life, responsibilities, relationships and hierarchies.

These artworks depict the brides and drummers integral to the ceremony. The composition is filled with five figures. The grooms, the drummers and the two brides with their backs towards us.

Mufangejo describes the scene clearly in the caption at the top of the composition:

The traditional clothing of the brides in the print is significant. Traditionally Kwanyama girls were required to follow a strict initiation ritual when they reached marriageable age. This ceremony is both a rite of puberty and a group marriage ceremony that is eagerly awaited by the girls. It would only occur every three to four years when enough girls participated.

The ceremonies were held over four days and were supposed to prepare the girls for the toughness of the life awaiting them. Continuous dancing to the sound of drums played by men was part of the ceremony.

After this, the girls had to attend a field school of eight weeks, during which they were forced to fend for themselves. As preparation for the field school, they had to create a unique headdress that was supposed to test their endurance as they had to create it in the blazing sun.

The omhatela-headdress is characterised by five horn-like points, of which the front three symbolise a bull, while the two horns positioned at the back symbolise the form of a cow. After attending field school, they were cleansed of the white ash covered with the field school initiation rites, and their bridegrooms were allowed access.

The young women continued to wear the omhatela-headdress as a sign that they had achieved married status. With time the headdress became untidy and unattractive it was replaced by a new one or simply discarded. The omhatela would also be worn if a widow or divorced woman re-married. These women were no longer subjected to any ceremonial obligations.

Muafangejo emphasises the women’s appearance as they are portrayed as larger than the men.

We see expressive movement in the drummer. The man seems older than the two bridegrooms as he has a long beard. He is bent over the long traditional drum that he holds steady between his legs. Muafangejo’s depiction of the detail of the drummer’s hands emphasises the action of drumming. The two bridegrooms raise their arms, with their hats in one hand, to recognise their brides’ performances.

The drummer and one of the bridegrooms wear Kwanyama knives of exaggerated size in wooden sheaths. With these artworks, Muafangejo conveys the importance attached to the initiation of girls and the following wedding ceremony in his traditional culture. He keeps the memory of it alive through this artwork. Traditional cultures are under threat. People are following western traditions because of their conversion to Christianity. Works such as these are valuable as a remembrance of that culture.

New Archbishop Desmond Tutu enthroned. Linocut. 1986

The announcement in 1986 that the new Archbishop of Cape Town would be Desmond Tutu was big news. This was South Africa’s first black Archbishop of Cape Town; with the country still in the grip of Apartheid, the eyes of the world were upon South Africa. Various VIP guests attend.

Muafangejo documented the memorable event for South Africans in his lino cut called New Archbishop Desmond Tutu enthroned.

The work consists of two strips of imagery with captions underneath each. The top depicts the New Archbishop Desmond Tutu – the shape of his head is exaggerated. His robe with chain contributes to the significance of his position.

His facial expression is solemn, and he holds the pointed finger of his right hand towards the crucifix of Jesus to remind people that they should not forget why they are there. From the left, a white dove enters the composition, symbolising the Holy Spirit entering Bishop Tutu. Next to the crucifix, two cupped hands, one white and one black symbolise prayer.

In the strip below, the church is jam-packed. People are depicted one black, and one white, spread equally throughout the rectangle with friendly facial expressions. In the row, a white and black man stretches their arms to take each other’s hands, encircling three other people.

This event was significant for South Africa as a country. SA was locked in the final stages of the segregation of races caused by Apartheid. It is a clear sign of the integration of the church in defiance of the country’s laws. The inscription is a blessing to Muafangejo’s support of the changes occurring in South Africa and his strong Christian beliefs.

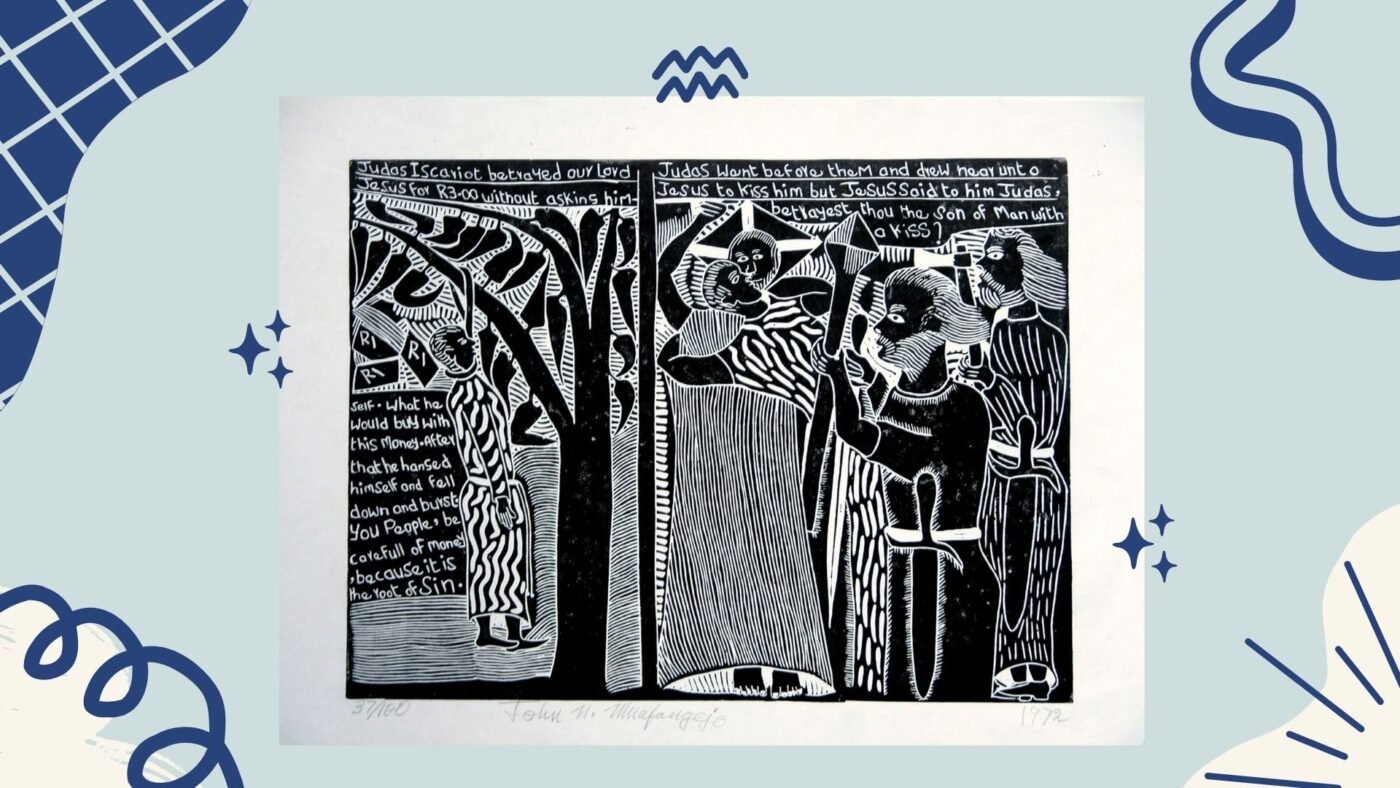

Judas Iscariot betrayed our Lord Jesus for R3.00 Linocut. 1973.

This artwork needs to be read right to the left and tells the story of Judas Iscariot betraying Jesus Christ in the garden of Gethsemane.

First, he depicts the scene where Judas is kissing Jesus in a dramatic embrace. On the left, we see the shocking scene of Judas’s suicide. He hanged himself after realising the gravity of his deed.

Judas is portrayed expressively in a position that looks like a serpent entwining Jesus. The print on his long dress resembles the scales of a snake. This starkly contrasts with Jesus’s dress, depicted with fine peaceful lines. This could symbolise the idea that Judas was possessed by the devil at that stage.

The title “Judas Iscariot betrayed our Lord Jesus for R3.00” immediately draws our attention as he used South African Currency. It was the amount of money that Judas was willing to take to be bribed. In the Bible, it is stated that Judas would betray Jesus for 30 pieces of silver.

When Muafangejo created the work, an R1 was a note, not a coin. R3.00 was worth more back then, but it was still not a lot of money. He was implying that Judas would have done anything for money.

Jesus’s feet are depicted in a frontal position, which creates the feeling that Jesus is floating. The two men on the right are armed; one holds a knobkerrie and the other an axe. These were soldiers, not disciples – probably on their way to arrest Jesus. Both have swords tied around their waists.

Muafangejo depicts the tree with large simplified leaves that resemble the shape of daggers or swords. He also depicted the three one-rand notes scattered uselessly on the ground. His caption is dramatic and informative, and it conveys the moral of this story:

A recurring theme in his work is the struggle between good and evil. He always wanted to convey a message that contained a lesson for the viewer, much like Jesus’s parables.

Conclusion

And that is an overview of this remarkable artist’s trailblazing award-winning, and trend-setting career. Muafangejo is considered one of his generation’s most important visual artists and Namibia’s most famous artist.

In a relatively short working career, he produced 260 prints, influencing generations of printmakers in Southern Africa. His artwork contains humour, social realism, contemporary history, mythology, religion and culture of the ovaKwanyama, Ovambo tribe.

He did not live to see the independence of Namibia, but the violent struggle for it formed the background for his art.

John Muafangejo’s legacy remains ever-present in Namibia today. You can shop various Muafangejo merchandise and a soundtrack to commemorate his life.

Muafangejo is still with us, and we are all inspired by his work.

Art Curator, Elize van Huysteen

Another Namibian, who celebrates Maufangejo’s work, Lize Ehlers voices,

“He was a genius. John Muafangejo has put Namibia on the map with his vivid linocuts and his art is a world-class representation of brilliance. He will remain one of Namibia’s greatest visual artists ever”.

Lize Ehlers

Sign off.

I am artist Lillian Gray, and I love teaching art and art history. Remember to subscribe and ring the bell to get notified when a new video is released.

This is a reminder that you can shop various worksheets for all ages online on our TpT website. Connect with us on social media, and let us know what video you want to see next.

Until next time.

BUY OUR RORKE’S DRIFT WORKSHEETS

Worksheet pack that includes notes and fun activities. Ideal for art students and history students to learn more about the Rorkes Drift art and Craft center