No products in the basket.

Art History, Visual Diary

5 Famous Visual Diaries and Sketchbooks

Visual diaries, journals and sketchbooks have a long, rich history. Our need as humans to record our lives and document what we see is such a deep primitive need. It reaches for immortality by leaving a lasting mark, standing up, and saying, “Here I am, see me. I exist”. It is one thing that makes us as humans special and unique on this planet.

The Lascaux caves in France recorded the daily life of cave dwellers. The caves in Elands bay South Africa show a unique KhoiSan ritual of a tribe initiating its new members and recording each individual’s existence.

When a paper-like substance known as Papyrus was developed, it became easier to record daily life. One of the oldest diaries known to us is the Diary of Mere, which dates back to the reign of pharaoh Khufu during the 4th dynasty of Egypt. The text, written with hieroglyphs, mainly consists of lists of the daily activities of Mere and his crew on his boat.

The Chinese developed paper similar to the paper we know today (Han dynasty 202 BCE – 220 CE). Paper became central to the artforms of China.

Paper made its way to Europe and made books accessible to all. Books could now be carried in one’s hand rather than transported by cart. Which ultimately leads to that little sketchbook or Visual Diary you carry around daily.

Over the decades we have not only recorded our lives and daily experiences but also started plotting down our concepts and objectives. It became a way to keep track and revert back to ideas to explore them even further. Recording daily life become more personal and introspective.

Today as artists and designers, we have the privilege to look back at some of the greatest artists’ visual records. It helps us to peer into their creative thinking and better understand their thought processes.

In this video, I take a quick look at some of the most famous artists’ sketchbooks and visual diaries. In a previous video, I explained the difference between a Visual Diary and a sketchbook; please remember that the way we define a visual diary today has changed over the years. Some of these examples balance the fine line between a sketchbook and a visual diary. Some lean more towards journals; others are simply sketchbooks. The vital thing to notice is how these artists kept track of their thoughts, ideas, and inspiration over time. They did not rely on their minds to store their great ideas. Our minds are brilliant but not always reliable. It will remind you at 3 am about an assignment that is due tomorrow, while in class, it daydreams.

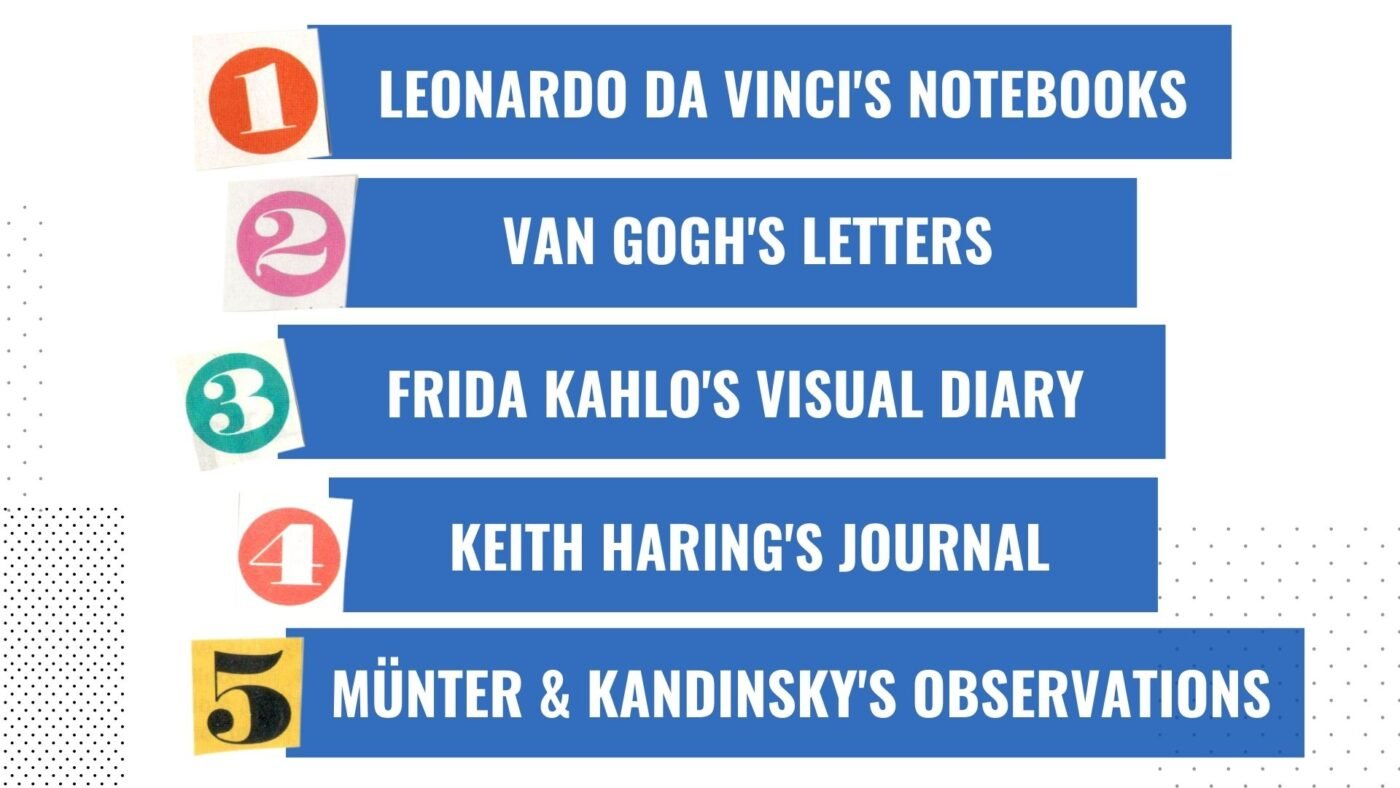

Here is a list of 5 famous visual diaries or sketchbooks by various artists. Stay tuned until the end of the video for a small bonus section on how scientists also used visual diaries.

1. Leonardo Da Vinci’s Notebooks

The most famous sketchbook or visual journal of all time is Leonardo Da Vinci’s. Leonardo wasn’t only an artist but an architect, a designer, inventor, engineer, and scientist. He had an unlimited desire for knowledge. Leonardo believed that sight was man’s highest sense. Every single experience that he observed became a source of knowledge. Leonardo was constantly developing new ideas; this often drove his clients nuts since he was distracted by new ideas and not finishing projects.

In his visual diaries, we see him recording ideas to enable him to fly, build giant war machines, explore the inner workings of the human body, or record the faintest movements of water. He even invented a mechanical knight for the Duke of Milan, which is considered today as the first prototype robot.

He combined his intellect, observation, and drawing skills to study nature, allowing his pursuit of knowledge in science and art to flourish. He is known for writing backwards using a mirror so no one could read or steal his ideas.

Leonard’s true legacy today is considered to be his visual journals. He only produced 20 paintings before his death. However, he made hundreds of sketches in his private visual journal. He started with his journals when he was 26 years old and continued to write an average of 3 pages a day until age 67 in 1519. It is estimated that da Vinci produced between 20,000 to 28,000 pages of notes and sketches spanning across 50 different notebooks. Bill Gates bought a collection of Leonardo’s visual journals for 30million Dollars.

Today this genius is credited with many inventions, such as the helicopter, parachute, armoured fighting vehicle, concentrated solar power, the double hull, and even the calculator.

Knowing how to see makes us artists or scientists

Lillian Gray

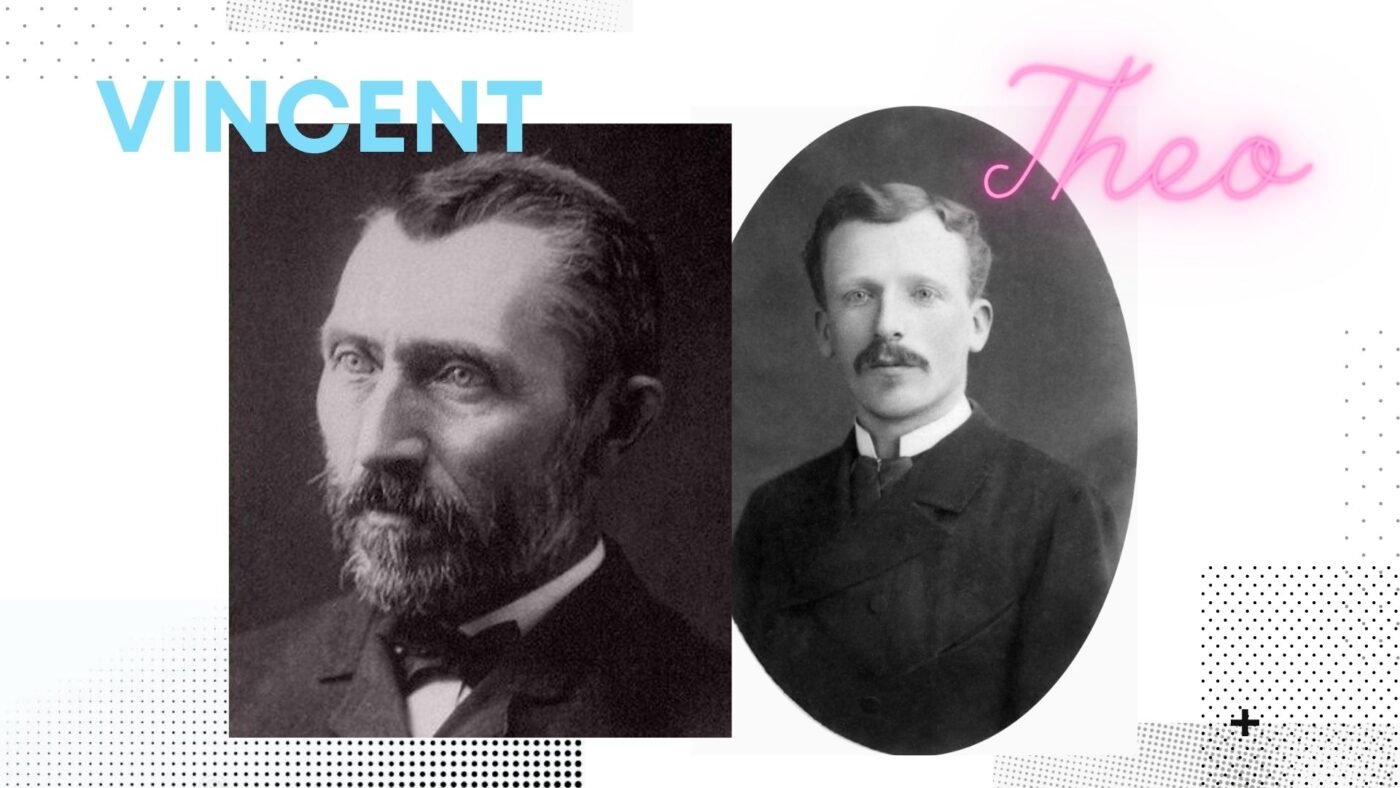

2. Van Gogh’s & Theo’s Letters

Next up, we have the letters that Vincent van Gogh and his brother Theo exchanged almost daily. People often think the Van Gogh family only had two boys, but that was not the case. There were six children in total. However, the relationship between Theo and Vincent was remarkable. Vincent was the misunderstood depressed genius artist, and Theo was a successful art agent. Theo supported Vincent financially and believed in his artistic abilities even though Van Gogh’s paintings didn’t sell. There were times that Van Gogh wrote Theo daily.

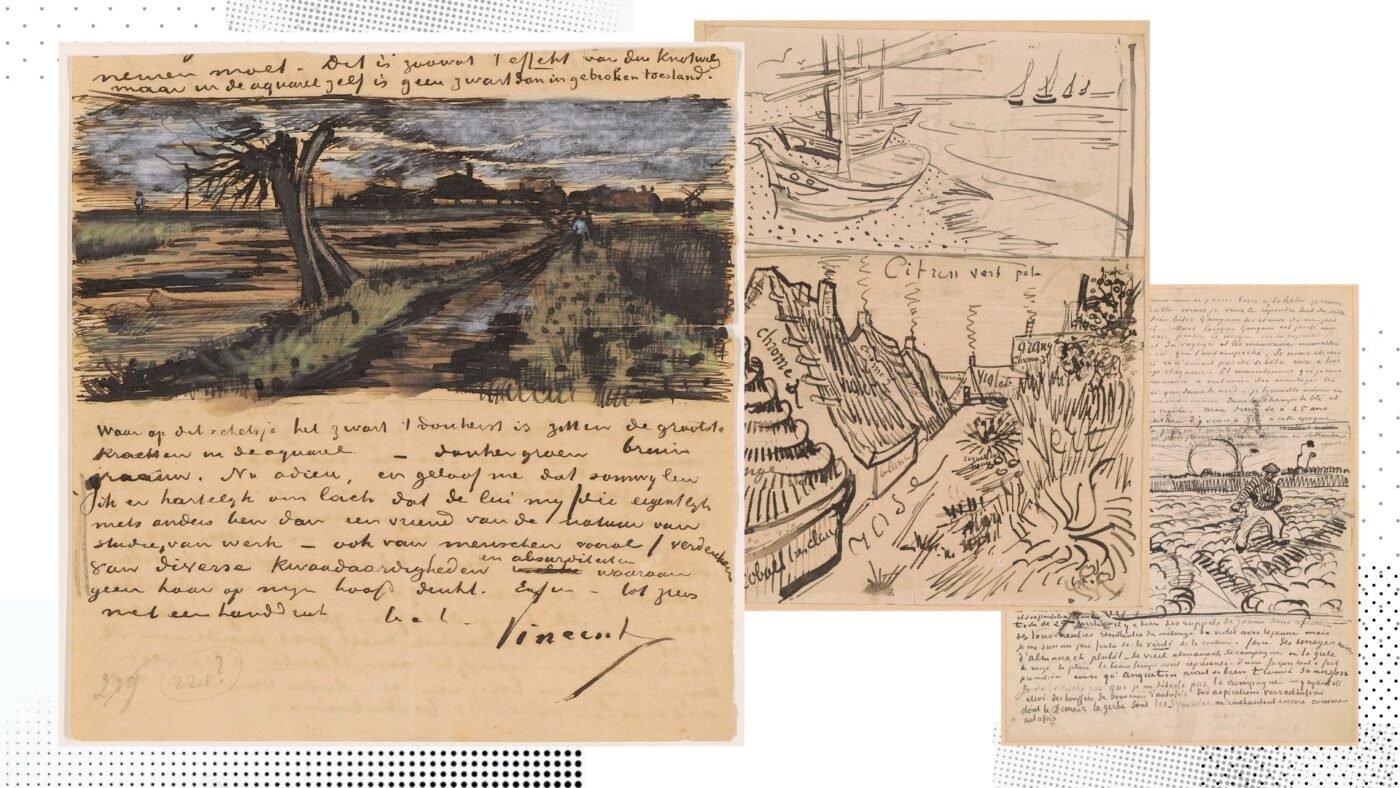

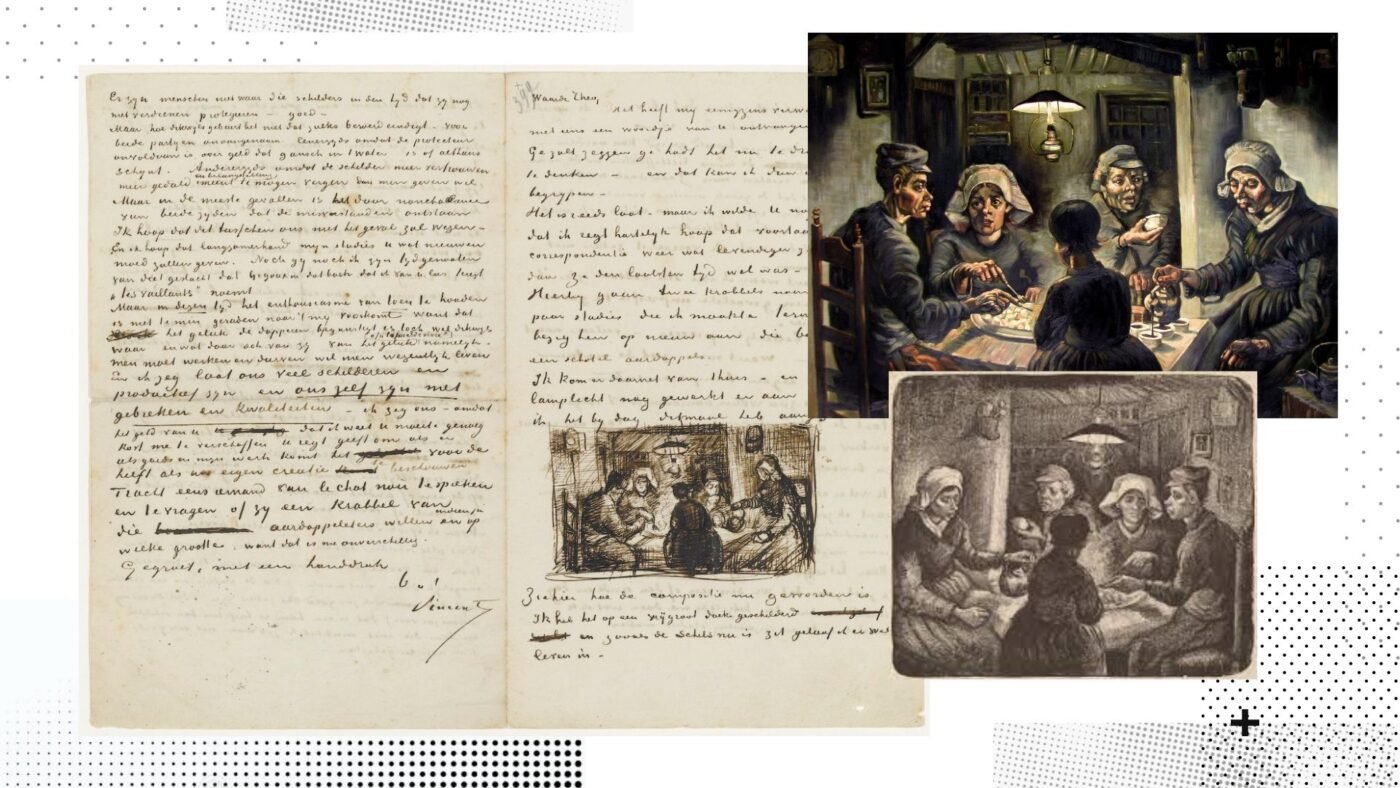

To this day, 844 letters written by Vincent van Gogh survive. Of the 844, he wrote 663 to his brother Theo. The first letter was written when Vincent was only 19. Today, these letters serve as a visual diary for Vincent Van Gogh since they explore various ideas and stories behind Vincent’s paintings. Vincent often included little sketched illustrations into his letters. He included sketches of ordinary people, such as miners and farmers, and landscapes. Letters to his brother are reflective and filled with his insights and philosophies.

Letters were written to fellow artists such as Émile Bernard, and Gauguin covers his techniques, use of colours, and various art theories.

Chronologically the letters form an autobiographical record of the artist. We can track his movements from Brabant, Paris, London, Antwerp, Arles, Saint-Remy, and his final destination Auvers.

Throughout his life, the tone of his letters changes. When stationed at the coal mines, it is filled with a sombre atmosphere and covers the hopelessness of Dutch peasant life. We can also see this mood reflected in his painting known as “The potato eaters 1885”.

The tone in his letters written in Arles is more positive. He describes his utopian dream of establishing a community of artists who lived and worked together. In this project, he was joined by Paul Gauguin in late 1888.

After Vincent’s tragic suicide, his brother died three months later. These incidents left Vincent’s sister-in-law, Johanna, with all his art and boxes of letters. One box filled with all the letters Theo wrote to Vincent and boxes of all Vincent’s letters to Theo. She started sorting through the letter and organising them chronologically. By reading them, Johanna soon realised that Vincent was, in fact, an artistic genius and had a unique way of seeing and conveying the world around him. She resolved to make Vincent’s artist’s genius world-renowned and became his strategic marketing strategist (before that even was a title). One of her strategies was publishing the letters as a book, which she did in 1914. Van Gogh’s correspondence became instrumental in spreading his fame.

Van Gogh is generally considered the greatest Dutch painter after Rembrandt van Rijn. His work has sold for record-breaking sums around the world. Partly because his journals have exalted him as an artist troubled by profound emotional experiences and religious and philosophical questions, this later inspired the script for the Hollywood movie Lust for life 1956 that would ultimately catapult Van Gogh’s worldwide fame. He is forever immortalised as the greatest Post-Impressionist painter that lived a tortured, troubled life.

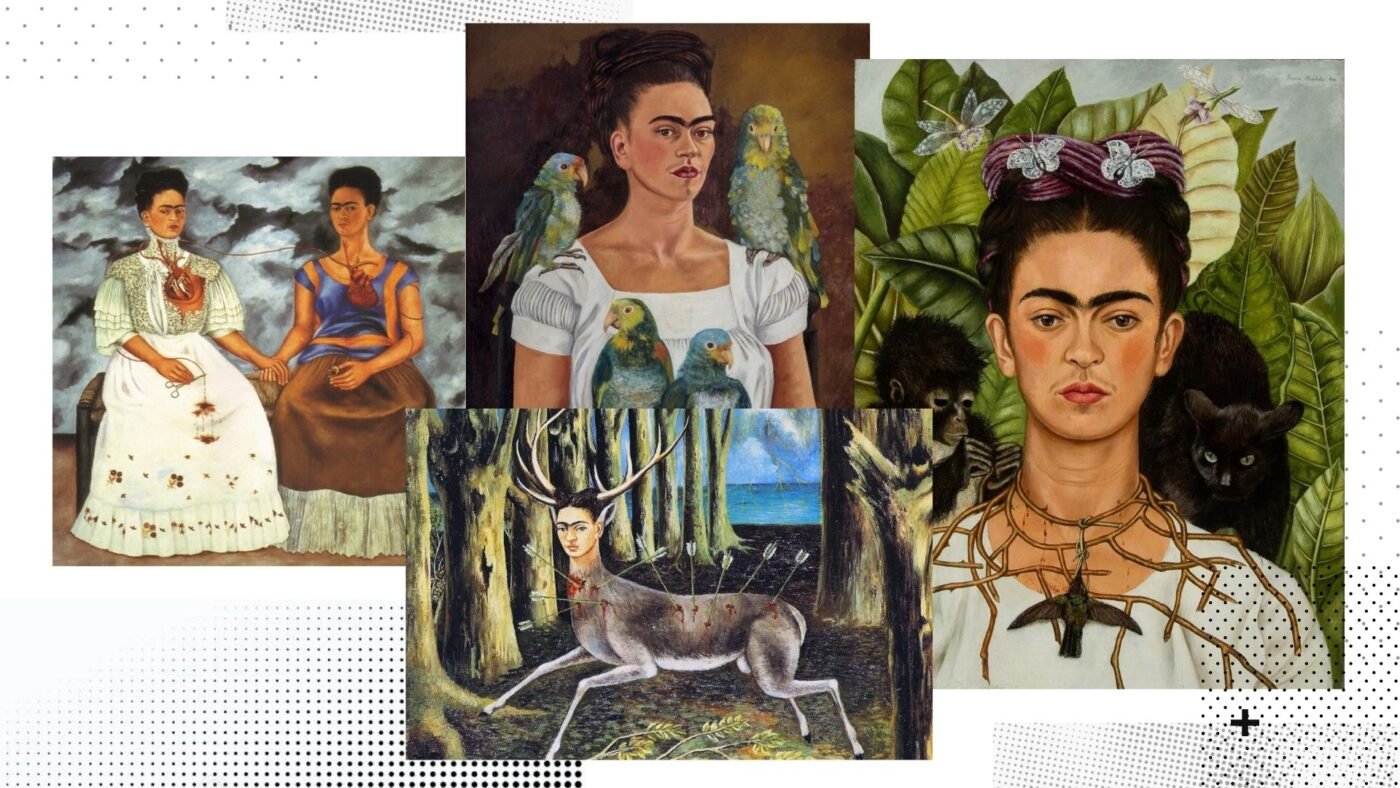

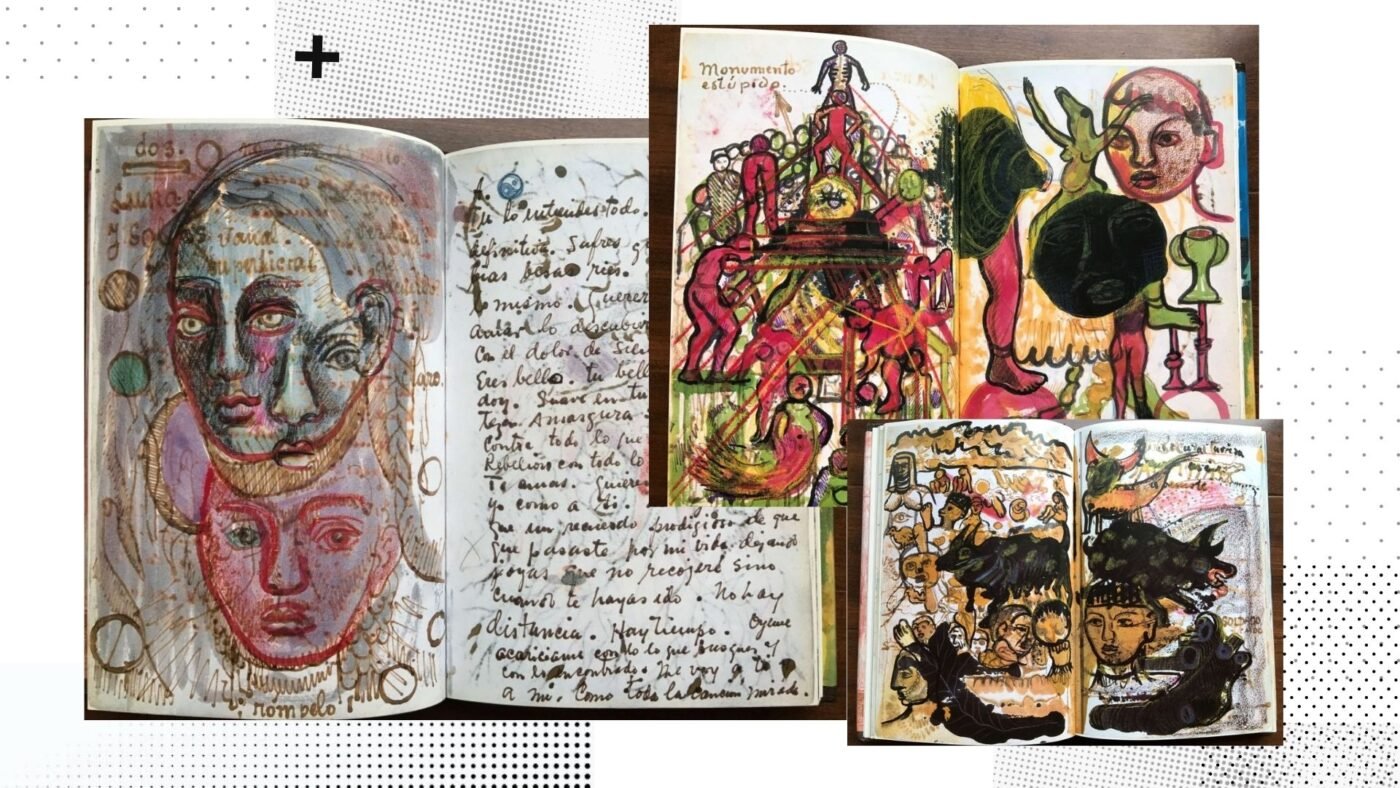

3. Frida Kahlo’s Visual Diary

Today the world suffers from Frida mania. What makes this Mexican woman with a unibrow so remarkable? For many, it is the way she dealt with tragedy and pain. She has shown many of us how to overcome trauma and disappointment. As a child, she suffered from Polio. As a young student, her body was severely damaged in a tram car and bus accident. She lived in tumultuous political times with the Russian Revolution and the rise of Communism. She was bound in love and devotion to an unfaithful husband and celebrated artist Diego Rivera.

For Frida, her art was cathartic – a way to deal with and release all her anguish. A sequential look at her artwork provides an understanding of the events that changed her life: her motivations, disappointments, passions and desires.

Frida only started keeping a visual diary at the age of 36 for the last ten years of her life. By then, she had already divorced and remarried Diego Rivera, her father had passed away, and she had undergone several surgeries and miscarriages with still more to come.

Frida’s paintings are carefully planned; however, her diary is created with impulse and freedom. The pages are not planned but rather a spontaneous release. The pages carry an impasto-like quality in the layers of text, scratch-outs, and drawings. Splotches and writing seep through the page, adding to the sense of all-consuming anguish.

Her diary is filled with symbols that relay this pain: teardrops, distorted bodies (with particular emphasis on feet and legs), lists, songs, letters, and fragments, all riddled with sources of suffering. We can also see strong influences in her work, such as Aztec Ruins, Mexican Culture, nature and animals, religion, and Communism. She also reveals her deeper connection to colour – Blue refers to “electricity and purity,” Yellow represents “madness, illness, fear, part of the sun, and happiness.”

The written part of the journal is filled with her tumultuous relationship with her husband, the Mexican artist Diego Rivera. One of the most potent images is a sketch that leads to a painting. She cradles Diego in her arms like a baby, while he holds the fire of creativity in his hands. Both artists are embraced by the Mexican earth goddess and the spirit of the universe.

Kahlo also describes a battle during the Mexican Revolution in her visual journal. She witnessed the battle at the age of four and credits this early exposure as the source for her political beliefs. The party’s revolutionary fervour gave her a purpose to survive. Throughout the latter part of the journal she analyses and reaffirms her faith in Communism.

In 1953, she was forced to amputate her gangrenous left leg; her spirit never entirely recovered. Frida wrote in her diary one of her most well-known phrases: “Feet, what do I need you for if I have wings to fly?”

According to Claudia Madrazo, a renowned art critic, “The diary is the most important work Kahlo ever did. It contains energy, poetry, magic.” Sarah Lowe said, “In Kahlo’s paintings, you see only the mask. In the diary, you see her unmasked. She pulls you into her world. And it’s a mad universe.” It is wild, hypnotic, and unplanned.

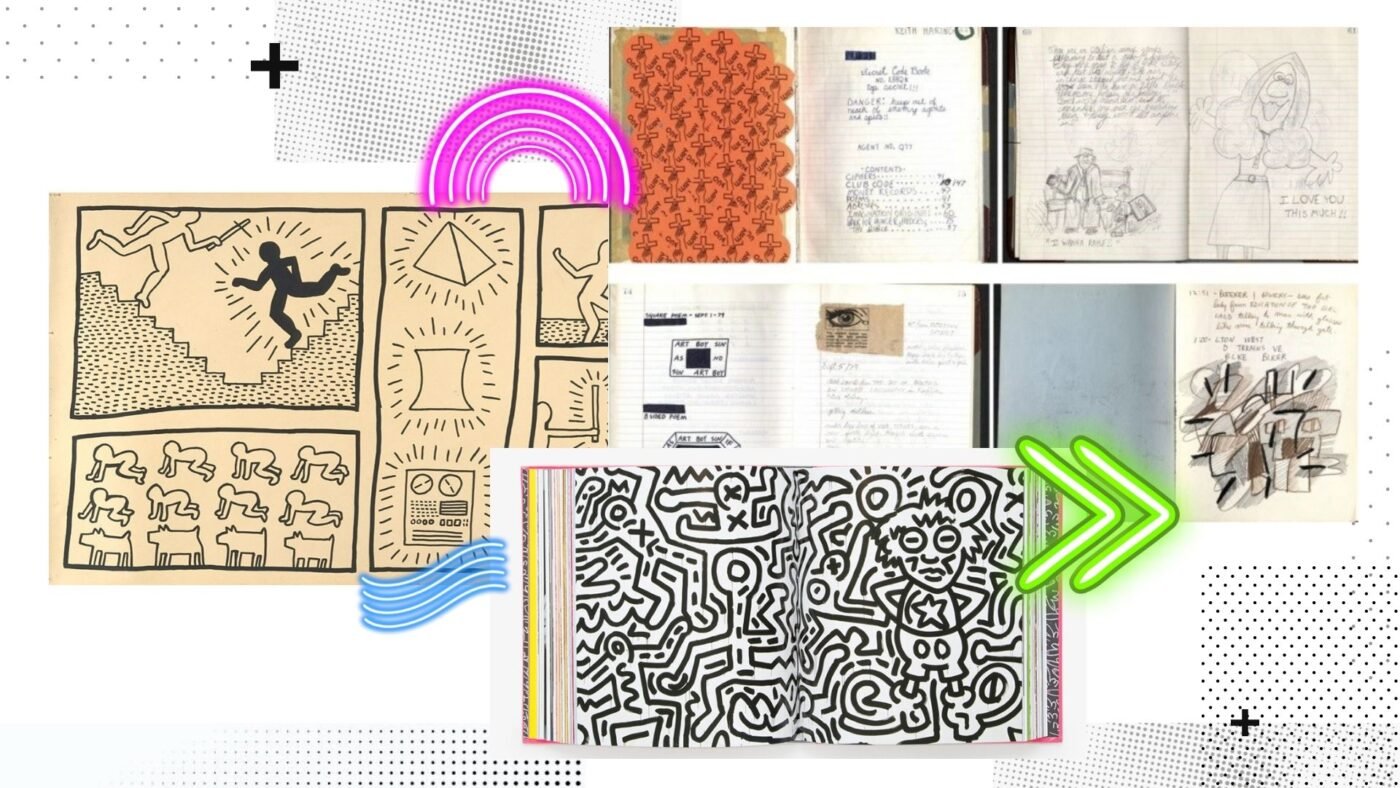

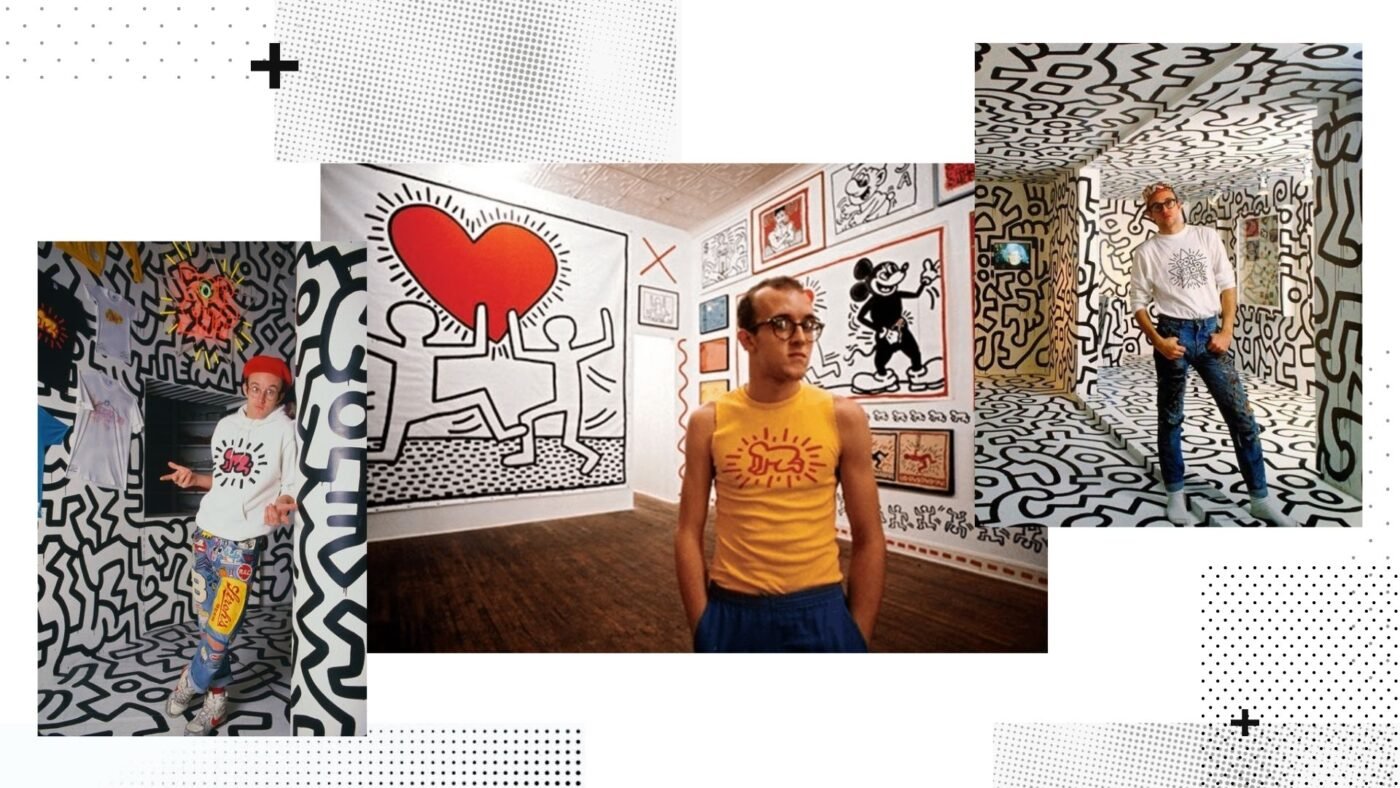

4. Keith Haring’s Journal

Keith Haring (1958 – 1990) is a pioneer of the downtown New York POP art scene of the 1980s. He is renowned for his spontaneous drawings of simple figures with bold lines. He has developed a coherent visual identity that makes his artwork instantly recognisable.

Rejected by high-end art galleries, Haring took to the streets to show his art. He aimed to make art accessible to everyone stating that “the public has a right to art.” Inspired by graffiti artists, he began drawing in New York’s subway stations. He filled empty poster spaces with chalk drawings that people would walk past every day.

“There is an audience that is being ignored, but they are not necessarily ignorant. They are open to art when it is open to them.”

Keith Haring

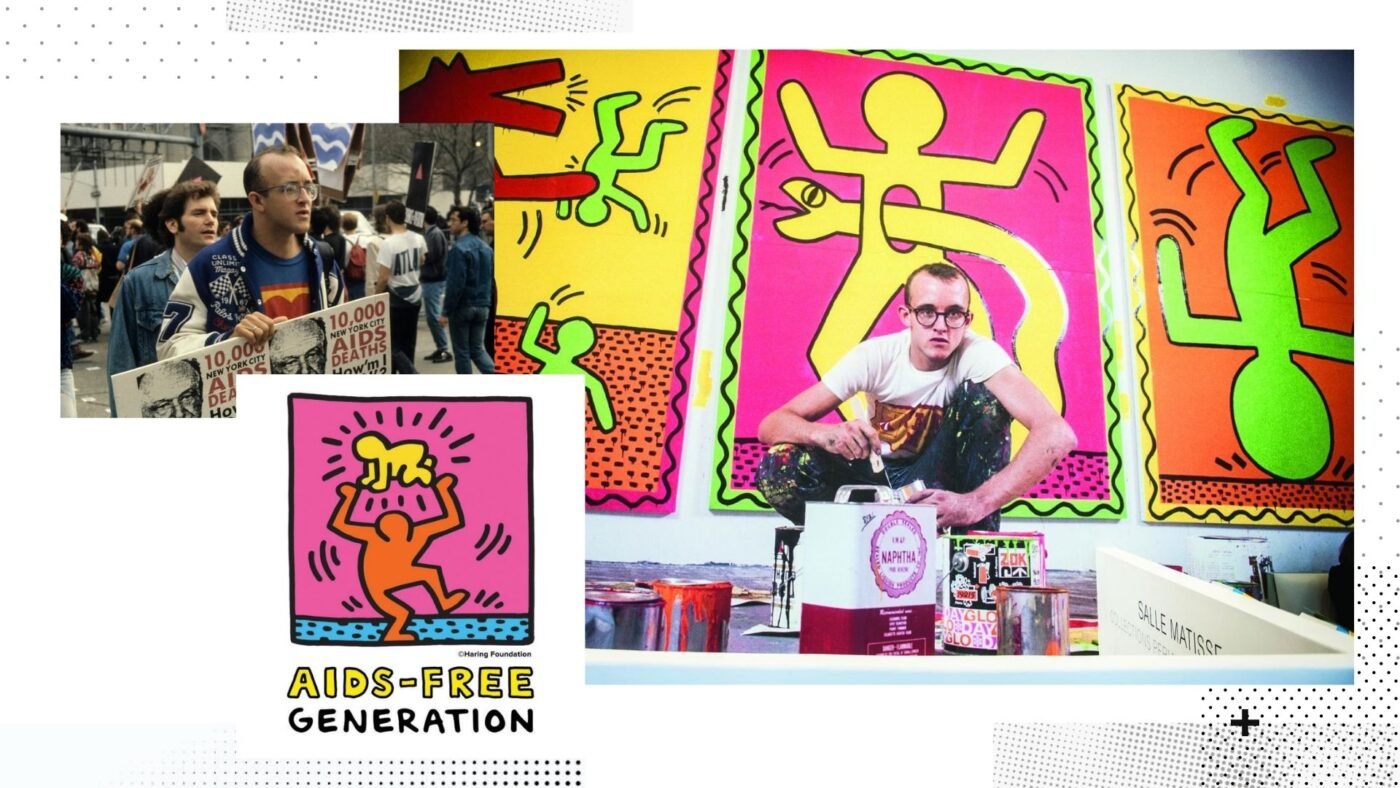

Haring is known for his colourful works and iconic motifs, such as the radiant baby and the barking dog. However, his work also addresses the social-political events of the time, covering AIDS, drug abuse, politics, the battle to end Apartheid, and LGBTQ rights.

He kept a vivid journal of his thoughts and travels. He started the journal as a teen and used it until his tragic death at the age of 31 in 1990. The journals attest to his hard-working nature and constant urge to create. They are not celebrated for his analytical insights. In the beginning, 1978 – 1980, the journal focusses on Haring’s arrival in New York and his ideas about the art world. It shows notes on art history and other artists, proposals for video projects, and future paintings and sculptures ideas. He was born and raised in a Christian home. His journals are filled with Christian symbols and apocalyptic visions.

During his career, many people who witnessed Keith Haring at work noted how his process did not rely on preliminary sketches. This is mainly due to work done in his Visual Journal. In his journal, we can see the development of the clean, precise linework he becomes known for. In his journal, He practised his drawing speed. He challenged himself to draw interesting compositions without preliminary sketches. He wanted to create in just one step, without hesitation, mistakes, interruptions, or corrections. His goal was to do legible work quickly before the police could catch him. From 1980 to 1985, Haring found his trademark cartoon-graffiti style. He rapidly became popular. His work featured on T-shirts, posters, hoodies, and urban murals.

Unfortunately, however, Haring wrote almost nothing during his transition from eager art student to international pop art celebrity. The journals resume as a record of his travels, oversee exhibitions and set up a store in Tokyo.

The latter part of the diary is overshadowed by death. In 1987 Keith’s mentor, friend, and art companion, Andy Warhol, died. Haring’s health started to deteriorate with his struggle against Aids. Knowing that his time is limited, he took delight in life’s mundane details.

5. Gabriele Münter’s and Wassily Kandinsky’s Observations

Recently I had the privilege of visiting the Lenbachhaus in Munich.

The Lenbachhaus is most famous for the extensive collection of paintings by Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), a group of expressionist artists established in Munich in 1911, including the painters Wassily Kandinsky, Gabriele Münter, Franz Marc, and Paul Klee.

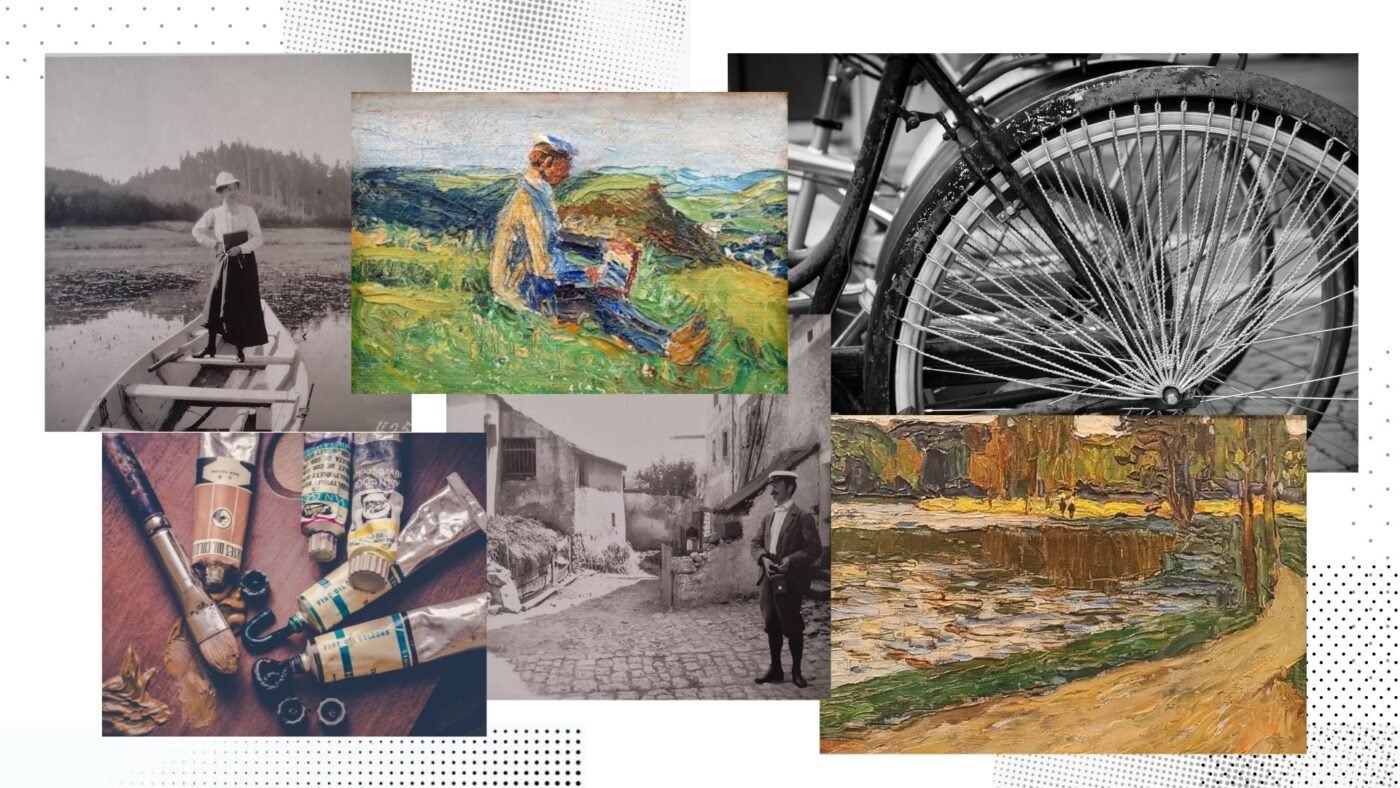

The museum is currently showcasing the close collaboration between Wassily Kandinsky and Gabriele Munter before The Blue Rider was founded. To me, it was simply fascinating. The exhibition reconstructs their travels and art pursuits from 1902 to 1908. The pair travelled light, with cameras, folding easels, paint tubes, and pasteboards. They created paintings and sketches in plain air and often travelled the landscape on their bicycles. They captured scenery and landscapes with photographs that inspired drawings, woodcuts, paintings, and oil pastel sketches. If all of these sketches, paintings, mini paintings were bound together in a book, it would make an impressive visual diary. They were capturing how each artist develops their style and perspectives. Due to constantly being on the road, the format of their work is small. We see the strong influence of the Impressionists on their work. They apply unmixed paint onto the canvas panels, not using brushes but palette knives.

Their wanderings ended when they decided to settle in Munich in 1908.

Other Visual Diaries – 3 Scientists that kept journals.

I want to veer away from Visual Artists and briefly show you how other historical figures used visual diaries to explore and document ideas.

1. Albert Einstein

The famous physicist Albert Einstein kept a visual journal. Few people realise that it took almost two decades for Einstein to be awarded the Nobel Prize for an idea he developed in his journal in 1902. In 1921 he won the Nobel Prize for Physics. Einstein started his journals at the age of 24. His research spanned from quantum mechanics to theories about gravity and motion. His one of the most notable works of general relatively spanned eight years, and his Zurich Notebook captures his work and views building up to the discovery.

2. Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin (1809-1882) transformed how we understand the natural world with ideas on the Theory of Evolution.

In 1831 Darwin obtained an offer to embark on a five-year voyage aboard HMS Beagle.

The journey would change both his life and the course of Western science.

Charles Darwin started to use his journal as a daily ritual on the voyage. He filled in more than 15 notebooks about his observations and findings.

Darwin explored remote regions and marvelled at the wonders of the world. He encountered sharks with T-shaped heads, giant tortoises and birds with bright blue feet.

Darwin collected plants, animals, and fossils on his travels and took ample field notes. These collections and records provided the evidence he needed to develop his remarkable theory on Evolution.

Darwin returned to England in 1836. A highly organised scholar, constantly collecting and observing, he spent many years comparing and analysing specimens before finally declaring that Evolution occurs by the process of natural selection. It is, therefore, safe to say that the journal played a considerable part in his contribution to his theory of Evolution.

Throughout his life, Charles Darwin kept diaries and secret notebooks. Darwin referred to it as the “little diary, which I have always kept”. His last entry was four months before he died. These records have allowed historians to piece together the thought from Darwin’s complex life. His theory on Evolution caused distress due to conflict with the Church, Victorian Society, and even his wife. The diaries give us insight into his theories but also these personal struggles.

3. Thomas Edison

The famous American inventor Thomas Edison (1847 – 1931) also kept a visual diary. He held a world record for over 1,093 patents. He played a critical role in the development of modern electricity. From his laboratory came the phonograph, the telephone speaker and microphone, the incandescent lamp, a revolutionary generator, the first commercial electric light, an electric railroad, and critical elements for motion pictures apparatus.

Edison documented his inventions with extreme details in a series of 3500 notebooks. Some sketches are crude and rough; others are done with the precision of a draftsman. The entire collection includes more than four million pages. The notebooks are filled with revolutionary ideas, captivating observations, and insights. Many ideas are unrelated and seem to jump between various technologies spontaneously. Some historians have compared his abundance of ideas with Leonard Da Vinci’s.

He also encouraged his colleagues to jot down diagrams and their ideas in his laboratories and workshops.

While Edison was not the inventor of the first light bulb, he came up with the technology that helped made it accessible to everyone. Edison bought a light bulb patent and improved the design.

While making 10,000 mistakes with the light bulb and 50,000 with the alkaline battery, Edison also prioritised extracting lessons from each of those 60,000 attempts so he could get closer to what could work. For Edison, there were no failures, only lessons learned.

Conclusion

And that concludes our presentation of 5 famous artists’ visual diaries as some highlights from prominent scientists.

From Eddison, we learn that a visual journal is not about hiding mistakes but instead embracing them and to keep delving into possible solutions. From Leonardo and Eddison, we can see the ability to generate not just one idea but multiple ideas and potential solutions for a problem. Frida and Van Gogh see how vital our opinion, understanding, and insights are critical to the creative process. From Frida, van Gogh and Keith Haring, we can see how we can develop our own visual language that is unique and can stand the test of time.

Leonardo, Van Gogh, Frida, Haring, Kandinsky and Muter used their journals and sketchbooks as tools. A means to record their ideas and master new techniques and skills. Even though some of these inventions and visual solutions were complicated, the process used was and is simple. We can all follow the method of keeping a journal or a visual diary. Our logical left brain fears the unknown. Sketching or writing a problem on a page allows our brains to approach the problem step by step. So regardless of which stage of life you are currently in, I would like to encourage you to start keeping a visual diary. If brilliant scientists and gifted artists all kept journals to constantly expand their knowledge, minds, ideas, and views, then what excuse do we have not to?